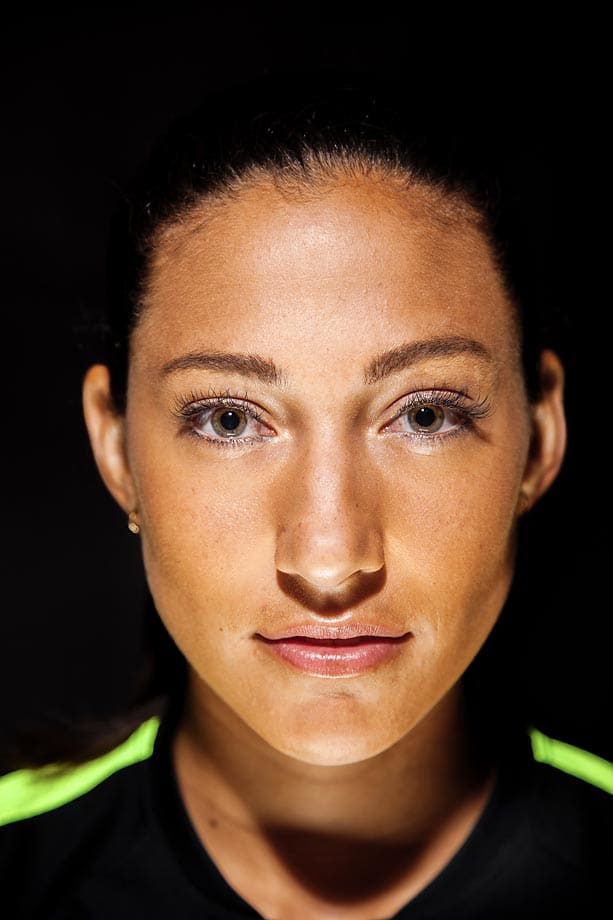

Christen Press's long U.S. national team road at last leads to World Cup

On January 31, 2012, Christen Press woke up to a text message from her teammate: “Oh my God, have you heard the news?” She opened her inbox and there it was–the email announcement that the Women's Professional Soccer league was folding.

Press was Stanford’s all time leading scorer, and WPS's 2011 Rookie of the Year, but she had never been invited to tryout for the national team, and now, according to this email, she was unemployed.

Press knew she wasn't ready to be done with soccer. The signing window for the European leagues closed in five days. She picked up the phone, called everyone she knew, and five days later she found herself laying on a twin bed in a tiny hotel room in Gothenberg, Sweden, trying not to cry.

“Every big change that I've had in my life, I have one night that is just so overly dramatic and emotional, and that is usually the first night," Press says.

She watched the wind whip outside her window, wondering, how did I end up here?

2015 Women's World Cup predictions: Who will win it all in Canada?

As a kid, Press was twig-thin, soccer shorts always creeping up towards her armpits. She was the middle of three soccer-playing sisters who all grew up with shinguard tans, speed, and a love for competition.

Their father was a Dartmouth football player, their mother a tennis player, and they were a family who, in Press's words, “placed extraordinary value on winning.”

Her club team, Slammers FC, was a powerhouse: at the U-14 level, it did not lose a game. It won Nationals, Nike, Surf Cup, Gothia. And every time, Press was the MVP, the Golden Boot winner (“All four years of high school we called her “The Boot,” says her best friend, Nima. “It started because we were at her house and saw this golden boot, and we were like, ‘uh, what the hell is that?’”).

In the U-14 national championship, the Slammers won 3-2, and Press scored all three goals. Club coach Ziad Khoury says, “Anyone who saw her was like, “My god, who is this kid? And then their next question was: how come she’s not on the national team?”

As the top club team in the country, Slammers FC scrimmaged against youth national teams—and usually won. Against her own-age group national team, Press scored the winning goal. Still, while others on her team started getting asked to play for U-16, U-17, and U-18 national teams, she did not.

Meet the USWNT 23: The USA's 2015 Women's World Cup team

Press's father liked slogans, catch phrases –“You better bring your lunch pail” was her favorite. The phrase, as she puts it, “tips its hat to the blue-collar workers who were so hard working that they barely took time for lunch.” That became her M.O.

“There’s a lot that’s out of your control. But the one thing that you can control is your work ethic,” she says.

Her mother had read that Pele took 100 shots every day with each foot, so Press decided that’s what she would do: every day after or before practice, she took those 100 shots, first with her right, then with her left, her mother and Coach Khoury fetching balls out of the trees behind goal.

In 2007, she left for Stanford and she had two main goals: win a national championship and earn a call up to the national team. While she had what would many would consider to be mind-blowing success– scoring an unprecedented 71 goals—she saw college as a failure. Press lost in the national championship two years in a row; and while teammates were getting called into full national teams—Kelley O’Hara to the United States, Ali Riley to New Zealand, and Teresa Noyola to Mexico—she was not.

She put huge pressure on herself to score goals: “Every time I shot the ball, there was always that thought, if I can’t score in this game, I won’t score enough goals by the end of the season, and then I can’t prove I’m good enough for the national team. And I have to prove that I’m good enough for the national team…because maybe I’m not.”

U.S. Women's World Cup Team: Christen Press

In 2009, she did get her first chance to play with a youth national team–called into the U-23s, the holding zone for players who’d aged out of the U-20 team but who have not yet made the cut for the full team. In camp, the U-23s scrimmaged against the full team, and sometimes the younger players got pulled up. Press, again, scored goals. But while there were U-23 players coach Pia Sundhage took aside to talk with at the end of camp, Press wasn’t one of them. Sundhage had her team in mind and Press wasn’t on it.

Then-assistant coach Jill Ellis, who’d faced Press in College—Press scored two goals and assisted on the other in Stanford’s 3-0 victory over Ellis’s UCLA team—did pull her aside. “You have all the pieces. The things right now you don't have is just the experience. You belong in this environment, and I think your time will come," Ellis said.

USWNT's Alex Morgan had late start yield meteoric rise in women's soccer

Press’s senior year at Stanford, she scored a nation-best 28 goals and won the Herman Trophy—beating out Alex Morgan. Beginning her professional career with MagicJack in WPS, she had one goal: attract the attention of the national team coach, prove that she was ready for the next level.

She scored eight goals in 17 games. She did not receive a call up.

“I had no idea what I was doing wrong. There’s no feedback, it’s just radio silence. It’s not like you get a phone call, hey, if you just learn to cross the ball better, we'll call you in,” says Press. “Were they that much better than me? If you get called in and you get cut, then you know. But if you never get called in, you never get to know.”

The answer was that the national team was full—Morgan and Sydney Leroux, who, unlike Press, both came up through youth national team pipeline, had gotten the coveted invites–and when they got there, they did well. Morgan scored in extra time to give the United States the victory over Italy it needed in order to qualify for the final spot of the 2011 Women’s World Cup. And when Leroux made it on the team in 2012, she scored a record-tying five goals in the 13-0 slaughter of Guatemala. Then of course there was Abby Wambach, interational women's soccer's all-time leading scorer. The national team did not need another forward.

This happens in men’s soccer too of course–when only 23 can make a roster, talented players get left off. One memorable example is Neymar–left off the 2010 Brazil World Cup roster, he was told, like Press, that he had to wait his turn.

But in the men’s game, even when you are not included on the national team squad, you can still be a star, worshipped by your country. In women’s soccer, when you are not on the national team, nobody knows who you are.

It's February 2012. Press is sitting on a bench in the locker room in Gothenberg, Sweden. She’s arrived in the middle of a snowstorm. In Sweden, there’s a rule that you cannot play if it’s below negative 18 degrees Celsius (0 degrees Fahrenheit). So the team is watching the thermometer and waiting.

Abby's Road: Wambach's motivation, quest for elusive World Cup glory

Press has on nothing but a T-shirt and shorts. Her teammates are blow-drying their toes. Her coach is giving out instructions in Swedish and everyone but Press understands what is going on. When the thermometer climbs to negative 17, they head outside. The fields are heated, which is supposed to melt the snow, but when it’s snowing at such a fast rate that it won’t melt in time, you get a snowball effect.

And the kid from California who cannot feel her feet is thinking, 'Oh my God. I don’t know if I’m going to survive this. But then came the next thought: “I’ve got to go all in, I have no other option, I either play here or I am literally retiring.”

In the next months, she did what she’d always done: she scored goals, lots of goals, only now she was playing with a completely unfamiliar feeling of freedom.

“I gave up on the national team – I thought to myself, well, that’s just not’s something that’s going to happen for me. The national team was in residency camp, I was 6,000 miles away. Nobody was watching, nobody cared … I’m just going to go play for myself and my team and try to be great … and I had more fun than I’d have ever had.”

Playing for Göteborg FC coach Torbjörn Nilsson, known in Sweden as “Football Scod”—the God of Football—Press's game evolved. Like Press, Nilsson was a center forward who had set records for goals. She had full intention of taking advantage of that.

“I didn’t want to miss out on all that knowledge," she said. "I told him at the beginning, I can’t understand anything you say in practice, and I can’t get better that way, so I need to have a one-on-one meeting with you every week and try to communicate.”

Every week they walked the field together, using charades and Google Translate to get by.

USWNT midfielder Carli Lloyd makes determination her defining trait

“He’d say to me, ‘I have to teach you everything.’ Because the way Americans play soccer is very different than what he believed. Like, communicating without speaking. In Sweden, if a player has the ball, and you’re running across the line of vision, you would never call for the ball. In the United States, if you’re open, you’re screaming. He told me, ‘You’re scaring all the players. You can’t scream like that.’”

One day in April, after she’d taken her rounds of 100 shots, she was in the locker room by herself when the phone rang–to her shock, it was the United States national team inviting her to come to camp.

National team manager Pia Sundhage, a Sweden native, took note of Press’s dominance in the Damallsvenska league. One month later, Sundhage took Press to the 2012 Summer Olympics in London as an alternate. Training with the team, while knowing there was no chance she’d see the field, she played with the same freedom she’d found in Sweden.

“I had nothing to lose,” she said.

In February of 2013, she got her first cap, and her first start.

USWNT team doctor: Artificial turf takes toll on recovery time, bodies

“I remember walking through the tunnel and thinking, 'Wow, I'm not even nervous, I'm gonna be fine,' and then you know, walking out and there was almost 20,000 people in the stands and I had never played in front of a crowd like that. And the very first touch I took on the ball was an easy shot and the ball came around and I went to shoot it and there was no power in my leg, I was so nervous. But lucky for me, I got my second shot and I had lots of power and I scored.”

Nineteen minutes later, she scored again. In her next game, she scored yet again—becoming the only woman to score three goals in her first two games for the U.S. national team.

Still, she was yet to become a household name. In 2013, playing for Tyreso FC, she was the leading scorer in the Swedish league (23 goals), outscoring Marta, the five-time FIFA World Player of the Year. And while Press has been an undeniable force since her start with the U.S. national team, scoring 20 goals in her first 41 games, the vast majority of people only pay attention to women’s soccer for two events–the Olympics and the World Cup–neither of which she had yet to experience.

Brazil's Marcelo, Neymar pose with the USA's Christen Press, Meghan Klingenberg at the 2012 Olympics in London.

Courtesy of Christen Press

In London, at the 2012 Olympics, alternates Press and Meghan Klingenberg were playing table tennis when members of the Brazil men’s soccer team filed out of a meeting and hovered around the hotel ping pong table.

Meet the U.S. Women's World Cup team: Forward Christen Press

Press was sweating, she was embarrassed, because she is bad at ping pong and she doesn’t like being bad at anything. When Real Madrid’s Marcelo joined Klingenberg’s side of the table, and said something to the extent of “Habla Espanol?” Press nodded—but when he followed with another question and she tried to respond, Swedish tumbled out. (“I thought, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me-now I know Swedish?”)

At this point, when another Brazilian joined her side of the table, she couldn’t even look at him. The doubles match continued, Press's team won, and finally she looked up–to see none other than Neymar coming at her for a hug.

And while Press of course identified him as one of the greatest players in the world, Neymar had no idea who he was hugging–at this point, she was only an American alternate, a beautiful girl he’d never seen on the field. Three years later, Press, now 26, will finally have the chance to introduce herself to the world—and to prove that she, too, is great.

Gwendolyn Oxenham is the author of Finding the Game: Three Years, Twenty-Five Countries, and the Search for Pickup Soccer and the co-director of Pelada. Her website is gwendolynoxenham.com and she can be followed on Twitter @gwenoxenham.