Book Excerpt: How Roberto Clemente inspired the Molina baseball family

Adapted from "Molina: The Story of the Father Who Raised an Unlikely Baseball Dynasty" by Bengie Molina with Joan Ryan. Copyright © 2015 by Tres Hijos Entertainment, LLC. Published by Simon & Schuster.

Many stars have emerged from the ball fields of Puerto Rico since baseball arrived on the island in the late 1800s. There were Hall of Famers Orlando Cepeda and Roberto Alomar. Superstars like Pudge Rodriguez, Javy Lopez, Juan Gonzales, Juan Pizarro, Ruben Gomez, Bernie Williams, José Valentin. More than 200 players from Puerto Rico have played in the Major Leagues since Hiram Bithorn paved the way in 1942.

Puerto Rico was so proud of its baseball stars that schools closed on the day in 1954 when Ruben Gomez — El Divino Loco — pitched for the New York Giants in Game 3 of the World Series. He was the first Puerto Rican ever to pitch in a World Series. The Giants won the championship, and when Gomez landed at the San Juan Airport, thousands turned out to greet him. The governor declared the day a national holiday.

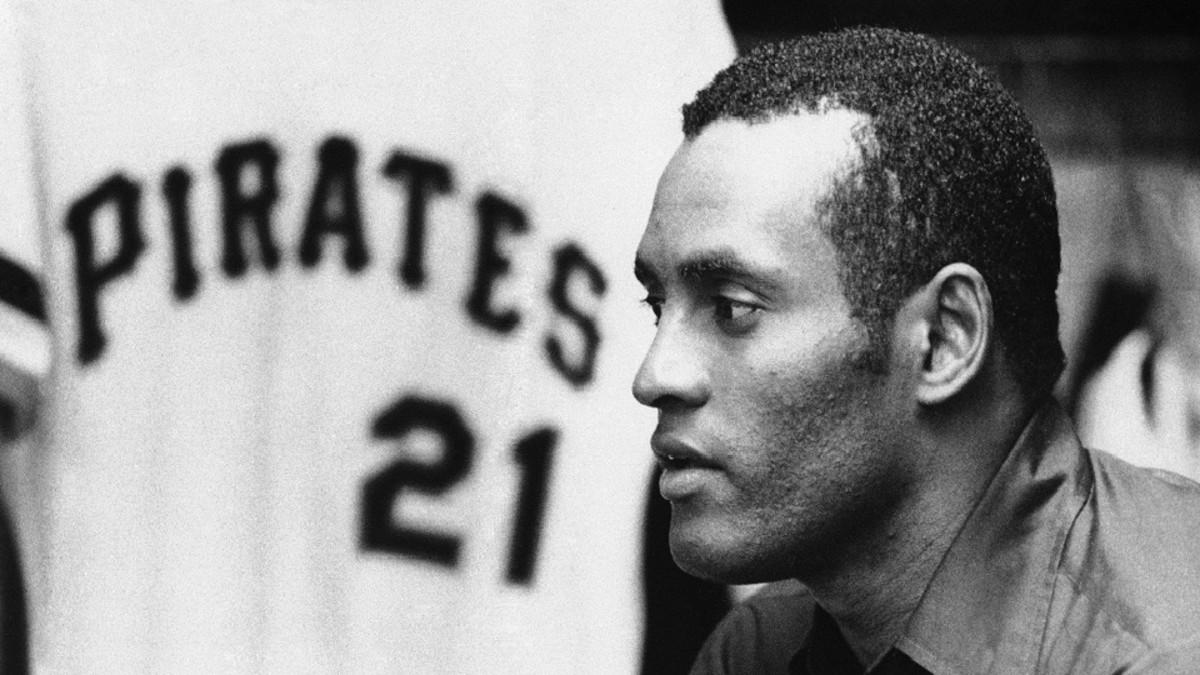

But Puerto Rico never had a hero like Clemente. In many houses when I was growing up, including ours, the portraits of two famous men hung in honored spots among the family photos: Jesus and Roberto Clemente. Most of us knew more about Clemente: Signed by the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954 when he was 20; won the World Series in 1960; voted National League MVP in 1966; won a second World Series in 1971; hit his 3,000th and final hit of his career on Sept. 30, 1972. But that’s not why he was revered.

He grew up in the coastal town of Carolina, east of San Juan. He was eight years old when Bithorn became the first Puerto Rican in the Major Leagues. But Bithorn was white, like the other Latin players who were breaking into the Majors. Clemente was black. No one in the big leagues looked like him. So he turned to the Negro League for role models. As a boy, Clemente rode the bus to San Juan to watch the Negro League stars who played ball every winter in Puerto Rico. He saw Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, and his favorite, Monte Irvin, an outfielder with the Newark Eagles. Irvin could throw the ball a mile. He could catch anything. He flew around the bases. But he wasn’t welcome in the Major Leagues.

The racism in the United States confounded Puerto Ricans. In Puerto Rico, people were all different colors, yet nothing kept them from eating at the same lunch counter, or sleeping in the same hotel, or marrying one another. Clemente’s mother came from Loiza, a town founded by slaves who had escaped from the Spanish army. Clemente’s father, a foreman in the sugar cane fields, was born just 10 years after slavery was abolished on the island in 1873. But there was no societal division between the descendants of slaves and the descendants of the governing Spaniards.

Clemente made his debut with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1955, just six years after Monte Irvin finally reached the Major Leagues as the first African-American player for the New York Giants. Clemente found that the color barrier might have been broken, but it had hardly been destroyed. During spring training in Florida, Clemente had to stay with a black family in another part of town while his white teammates stayed in a hotel. He had to wait in the bus as his teammates ate in roadside diners. He was often quoted by American sportswriters in cartoonish, broken English, feeding into an image of Latinos — especially dark-skinned Latinos — as uneducated and dumb.

But Clemente was so spectacular on the field and so noble off it that he transcended stereotypes. With quiet righteousness, he spoke out on issues of equality and social justice, elevating his stature beyond the sports world. After the Pirates won their second World Series, Clemente pointedly began his postgame press conference in Spanish, speaking directly to the fans watching in Puerto Rico and throughout Latin America.

On New Year’s Eve in 1972, Clemente took off in a propeller DC-7 airplane from Puerto Rico to deliver relief supplies to Nicaragua, which had been devastated by an earthquake. The plane crashed into the ocean soon after takeoff, killing everyone on board. When the news spread, people from every corner of Puerto Rico flocked to the beach at Isla Verde, their eyes searching the dark ocean as if expecting Clemente to walk ashore. Only the body of the pilot was recovered. Divers found the briefcase Clemente had been carrying. Three months later the Baseball Writers’ Association of America held a special election to vote Clemente into the Hall of Fame, bypassing the required five-year waiting period.

Clemente was all the evidence [my father] needed to support his belief that baseball beat out religion six ways to Sunday in turning out strong, decent men.