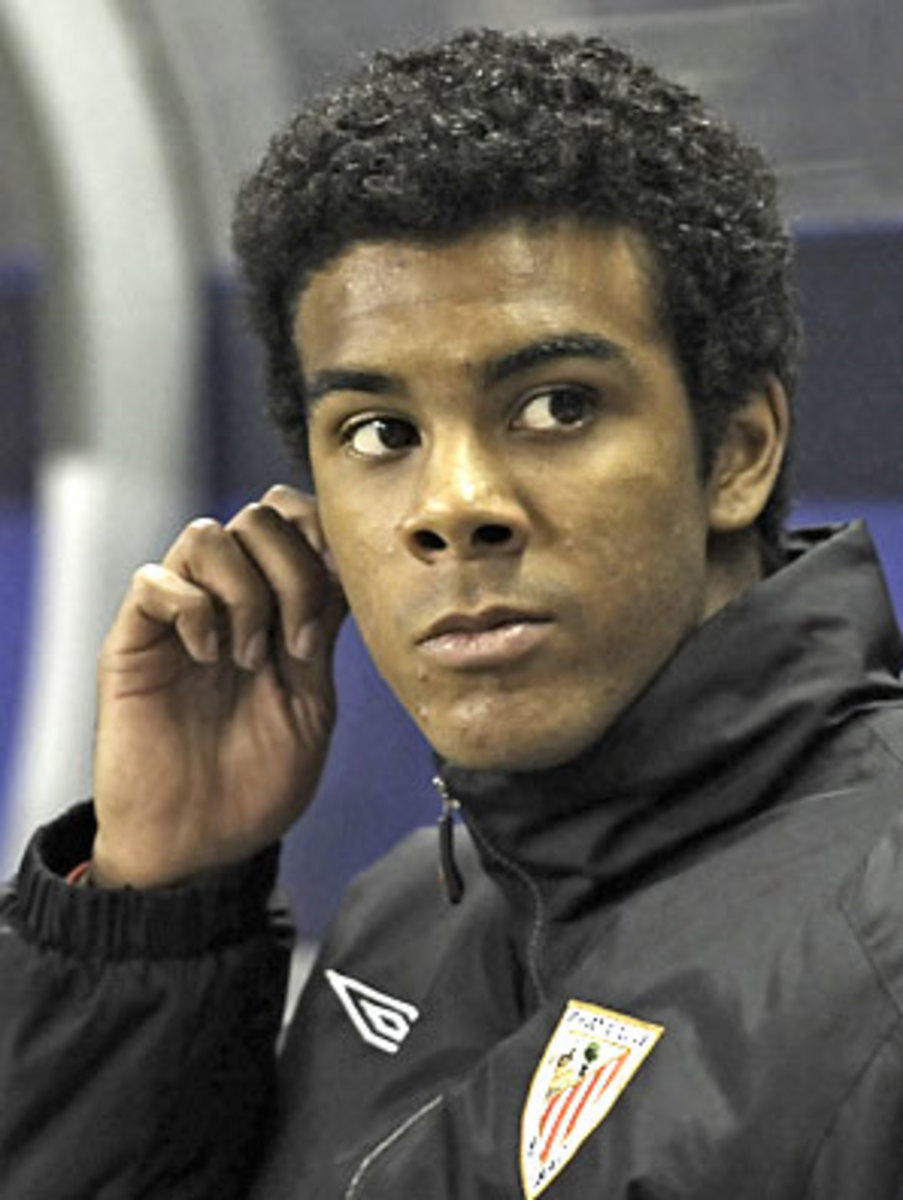

Jonas Ramalho helping to dispel longstanding Athletic Bilbao myth

Off came Iñigo Pérez and on went Jonas Ramalho. Ramalho is an 18-year-old who can play at right back and center back and on this occasion was asked to play in central midfield. He is tall and quick, he is good in possession, he is Iker Muniaín's best friend, and he is a European Champion at the U19 level.

He is also black.

Ramalho is the first black player ever to play for the club. He had made an appearance for Athletic as a 14-year-old in a pre-season friendly, he was included in the squad that faced Werder Bremen in the Europa League and he played for Athletic in a friendly against Paraguay. But this, at last, was his competitive debut in the Spanish league. When he came, not only did he break a barrier; he also helped to break one of the remaining myths that surround the Basque club, putting to bed an accusation often sent Athletic's way.

It has taken over 100 years for a black player to make his debut for Athletic. A couple of others have been close: in the 1950s there was talk that they might sign Miguel Jones, born in Equatorial Guinea, but the club decided against it. Half a century later, there were rumours of them signing another man with roots in Equatorial Guinea: the midfielder Benjamín Zarrandona.

In 2009, Benjamín told a Spanish radio station: "Athletic wanted to sign me when I was still playing at Valladolid. Some said that the reason they didn't was the color of my skin. Luis Fernández [the coach] told me that and so did someone else. Members have a vote [in presidential elections]. We're talking 10 years ago -- it was not like it is now."

When the revelation was made, Miguel Jones's case was revisited. Some raised the old specter: Athletic as a racist club. Jones had lived in the Basque Country since he was 5, played football in the Basque Country and ended teaching economics at Deusto University in the Basque Country. But, some said, he was black. And that was why Athletic would not sign him. Jones, though, was having none of it. "The idea that I didn't play for Athletic because I was black is media rubbish," he said recently. "They didn't sign me because I was not from [the Basque province of] Vizcaya. I was born in Equatorial Guinea [in 1938] and came to the Bilbao at the age of 4."

Jones' case is easy to support. That same year there was talk of signing Chus Pereda and José Gárate. Neither signed. They were not from Vizcaya either. Like Jones, they had played all their football in the Basque Country, appearing for Indautxu, barely one hundred metres from Athletic's San Mamés stadium. Pereda had even captained Vizcaya's U16s and described himself as "Athletic through and through". But Pereda had been born in Burgos and Gárate was born in Argentina. They were also both white. But they weren't born in the Basque Country. Nor was Benjamín.

And that was the key.

Since 1912, when Veicht and Smith departed, Athletic Bilbao have had what is commonly described as a "Basque-only policy." They have come to be considered a kind of unofficial Basque national team -- even though there is now a Basque representative side that plays annual friendlies. The policy has never been written down -- to do so might even be illegal -- and over the years it has undergone changes in interpretation, shifting with society, policy-makers and presidents. At times it has been stricter; at others, more flexible. It has, as Jones found, even been restricted to the province of Vizcaya alone.

In essence, the policy has largely hung on the simple notion of all players being Basque, from one of the seven historic Basque provinces -- the three that make up the modern Basque Country, Navarra (disputed by some), and the French Basque provinces, known as Iparralde (the "northern zone" in Euskera). Only one French player has signed for directly for Athletic's first team. That was Bixente Lizarazu and although there was no question over his Basque status (just look at his name), the decision was still a controversial one.

The problem is: what counts as Basque? Who does? Is it about birthplace?

Family roots? Upbringing? Language? (After all, for some theorists, the speaking of Euskera defines Basqueness.)

Athletic's policy is no more based on exclusion than any national team but the definition of nationality is always difficult. All the more so in this case. If there are gray areas for countries that are nation states, that can grant nationality and issue passports, how could there not be for a club like Athletic Bilbao? If there are doubts when there is a written rule, those doubts can only be greater when there is not one. National teams have co-opted players via the granting of nationality -- Spain played Marcos Senna at Euro 2008, for example -- so it is hardly surprising that there have been controversies with Athletic. There is no Basque state and no Basque passport which can serve as incontrovertible evidence of suitability for the Athletic team.

It is also not surprising that, in the absence of a uniform, state-sponsored set of rules, the definition of Basque has become a little elastic, embracing territories whose Basqueness is sometimes questioned. That is the case with all nationalities and there is a footballing reality too: when the Spanish league first started up, a little over 50 percent of footballers were Basque. Now, that figure is well below 10 percent. As a proportion of the footballing pool, Basque players are fewer; the ability to compete is reduced. Other avenues have to be explored.

Just ask Real Sociedad. The top flight's other big Basque club (even if some Osasuna fans in Navarra consider themselves Basque), were forced to ditch their own Basque-only policy. Feeling that they could not compete with the financial and political muscle of Athletic, Real Sociedad initially went for a policy of Basques and foreigners only but no Spaniards -- their first foreign signing was John Aldridge in 1989 -- and then, in 2001, they finally signed a non-Basque Spaniard when Boris joined from Real Oviedo.

These days, Gárate, Jones and Pereda could certainly play for Athletic.

Defender Fernando Amorebieta was born in Venezuela. His parents are both Basque, from Vizcaya. At the age of 2, the family returned to the Basque Country; it was more than 20 years before Fernando visited his country of birth again. Amorebieta is more Basque than Venezuelan -- but recently made his debut for Venezuela. If his status as an Athletic-eligible player is questionable, his status as a Venezuelan is too.

There are two basic criteria that define whether or not a player can play for Athletic now. One is nationality, with all that entails. Ander Herrera was brought up in Zaragoza and began his career with their youth system but was born in Vizcaya. And though it has not always been the case, Athletic now assume the suitability of all those from the seven Basque provinces, whether by birth, parentage or upbringing. The other is footballing formation. Athletic's policy states -- except that it doesn't "state" at all, of course -- that players are eligible if they are Basque and/or formed as footballers in the Basque Country.

That has seen them stress the importance of the work done at the club's Lezama youth academy, so often seen as Athletic's spiritual home, and also allowed them to sign players from other Basque clubs (with "Basque" defined broadly) if they have come up through the youth system there. Look at the current Athletic side and you will see players who began their careers at Osasuna as well as players from Alavés and Real Sociedad.

Athletic also have players that they have brought from elsewhere to form part of Lezama, joining the club at a pre-professional level. Much is said about the fact the club never signed Roberto López Ufarte because he was born in Morocco, even though he loved in the Basque Country from the age of eight and started playing there. These days, they would have no hesitation to do so. If a player is available at any youth team level in the Basque Country he is "signable."

In 2008, Athletic signed Enric Saborit from the youth system at Espanyol. He now plays in Athletic's B team. Saborit's dad is Catalan, his mother Basque; quite apart from his mother's "nationality," Athletic claimed that they signed him for their youth system because he had come to the Basque Country and therefore had entered into their sphere of footballing influence. The question was whether he had come because they had encouraged him to. Yanis Rahmani and Maecki Lubrano were both born in France (and not the French Basque Country): both are now in the youth system at Lezama. As is the Mali Binge Diabaté.

In fact, Athletic now have a reciprocal agreement with the French (Basque) third division team Aviron Bayonnais. To what extent players from Aviron Bayonnais would have to finish their footballing education at Lezama before making the first team or could jump from France to La Liga is yet to be tested.

Much has changed, but that does not explain this latest, most striking, debut. Jonas Ramalho fits both criteria: nationality and footballing formation. At any point in history he would have been eligible to play for Athletic Bilbao. Ramalho's passport is Spanish. His father Tomas is from Angola, his mother Natalia is Basque and he was born in Baracaldo, Vizcaya. He was raised in Leiona, just outside Bilbao, spending his entire life in the Basque Country. And he joined Athletic at the age of 10. His debut on Sunday should not have made a huge impact. But being black, it did.

His appearance is not a result of shifting policy: the criteria is not about colour; looking at the Athletic team over the years, though, colour has been a consequence. Why, people asked, have Athletic never had a black player?

Ramalho provides the answer. So, indeed, does the Spanish national team. Only five black players have represented Spain at senior level: Donato, Senna, Catanha, Engonga and Thiago. The first three are all Brazilians given Spanish passports having joined La Liga and become a success there -- an option not open to Athletic. (The latter two, meanwhile, are the sons of professional footballers who came to Spain, players who were formed as Spaniards and also had the opportunity to choose other countries to play for). Why? Because in a country, in a region, where immigration is a recent phenomenon and not a particularly widespread one, at a club defending a unique, Basque identity in world football, none have ever qualified before.

Jonas Ramalho does. Not least because he is very, very good at football.