The Forgotten Hero: Mike Reily's legacy at Williams College

For five decades Williams College kept the number 50 jersey packed away in a box, unofficially retiring it even though the school did not retire numbers. No one remembered who had last worn it or why it was not given out. Until last year.

In honor of Sports Illustrated's 60th anniversary, SI.com is republishing, in full, 60 of the best stories to ever run in the magazine. Today's selection is "The Forgotten Hero" by Tim Layden, which ran in the Nov. 7, 2011 issue.

On the last day of his short life Mike Reily awoke in a hospital bed at Touro Infirmary in his native New Orleans, barely a mile from the house in which he was raised. It was Saturday, July 25, 1964, and the temperature outside would climb to a sticky 91°. A single intravenous fluid line was connected to Reily's body, which had been a sinewy 6'3" and 215 pounds before being withered by Hodgkin's disease and by the primitive treatments that couldn't slow its progress. Mike's mother, Lee, had been in the spartan room with him almost every minute of the four days since he had been brought in to die.

Three months short of his 22nd birthday and recently graduated from college, Reily must have known the end was near. This day had stalked him for 17 months. His childhood friend John Gage, who was heading into his second year at Tulane's medical school, had visited him in the hospital. "He was lucid, but he was beaten to death," says Gage. "People who are terminal eventually have a look. The life is gone. That's the way Michael looked. He told me that when I became a doctor, [I should] find a cure for this miserable disease."

SI 60 Q&A: Tim Layden on Mike Reily and an athlete dying young

Maybe as he lay there, Michael Meredith Reily also thought about things he would never see again: The flat, brackish waters of Bayou Liberty, where as a boy he had water-skied all day and never grown tired. The cold, green football field in faraway New England, where one November afternoon Williams College had upset Amherst and the rangy linebacker from New Orleans had been the best player on the field. The tall, blonde girl from Skidmore College with blue-green eyes, the kind of girl you never forget whether you live one more year or 100.

But Reily could not have imagined the ways he would endure in memory. He could not have known what older men learn: that friends and teammates are never really forgotten, and those who live largest and die soonest are remembered in the most poignant way. He could not have known that nearly half a century after his death, those who knew him best would still be haunted by his absence. He could not have known that men who served in combat would recall his courage in the face of death and compare it to bravery in battle.

• Read all of the stories and Q&As in the SI 60 series

And Reily surely did not know that on a late fall afternoon in the Berkshire Mountains of northwest Massachusetts, seven months before he graduated and went home to die, his young football coach and the college's equipment manager had made an impulsive decision to put away the purple, white and gold number 50 jerseys that he had worn on the field, and that over the next 47 football seasons five more coaches and six more equipment managers would quietly honor that decision, most without knowing why. They would leave the jerseys packed away, unofficially retiring number 50 at a college where numbers were not retired. And one day, quite by accident, the story of Mike Reily's jerseys would be unearthed, and the young man who inspired so many others would come back to life.

Fall 2010: The box

Early in October of last year, Ben Wagner was at home in Portsmouth, N.H., perusing the website of Williams, a small, highly selective Division III school in Williamstown, Mass. Calling up the football page, he found a section titled EPH LEGENDS. (Williams teams are nicknamed the Ephs or Ephmen after the school's founder, Col. Ephraim Williams, who was killed in 1755 during the French and Indian War.) Wagner, 69, had been an Ephs baseball player and co-captain of the 1963 football team, a 6'4", 235-pound offensive and defensive tackle whom everyone of course called Big Ben. The other co-captain was Mike Reily. Over the years Wagner had been disappointed that Reily was not listed among the Eph legends, not only for his dominant play but also for his courage as he faced death.

Wagner finally e-mailed the college's football coach, Aaron Kelton, to inquire about adding Reily to the list, and he encouraged his teammates to do the same. Wagner also got in touch with Dick Quinn, Williams's sports information director. Quinn, 60, had been raised in Williamstown and had begun working at the school in 1989. He recognized both Reily's and Wagner's names. Back in the 1960s kids in town attended Williams games in all sports; Quinn had been present when Wagner hit a baseball into the distant football bleachers, which had rarely been done. Quinn also remembered attending football games at which the public address announcer kept saying, Tackle by Reily. Tackle by Reily.

"You could not go to a game Reily played in and not hear his name over and over," says Quinn. "I remember hearing that Mike died the summer I was 13, and I was stunned. I knew he didn't play his senior year because he was sick, but I had no clue that meant terminal." Quinn asked the college's assistant archivist, Linda Hall, to dig up some photos of Reily, so that he could add Reily to the Web page. He told Wagner he was on the case.

Around the same time, Williams assistant offensive line coach Joe Doyle made one of his routine prepractice visits to the school's equipment room in Cole Field House, a three-story brick building that sits atop a steep hill overlooking a broad expanse of practice fields. Doyle, then 69, was a 5'10", 230-pound inside linebacker at UMass in the 1960s and later a high school coach in Cheshire, Mass. When he became an assistant principal in the mid-'80s, he was no longer allowed to coach high school football, but then-Williams coach Bob Odell made Doyle a volunteer assistant. Odell couldn't pay him, but he did get him a gift. "A nice sideline parka from the college," says Doyle. "I could wear it when it was cold." He picked number 50, his number at UMass.

A Name On The Wall: Football player Bob Kalsu was the only U.S. pro athlete to die in Vietnam

Now, on an October afternoon in 2010, Doyle sat with Williams equipment manager Glenn Boyer next to the washers and dryers and cleats and jockstraps and noticed an old cardboard football box on a shelf. The box was red on top, white in the middle and yellow on the bottom, with a Wilson logo on the side and the top. The cardboard was torn in a couple of spots, stained by water and sealed with six strips of deteriorating tape.

What caught Doyle's attention was a faded message written on the side of the box, in felt-tip marker:

FOOTBALL

#50 DO NOT ISSUE

The same words were written on the top of the box. Doyle asked Boyer what that was all about. The equipment man said, "We don't give out number 50."

"Why not?"

"I don't know," Boyer said. "We just don't." Boyer, then 50, had been working in the equipment room since November 1987 and had looked at the battered box nearly every day without ever opening it to see what was inside. He just left it alone and went about his business.

Curious, Doyle sought out Dick Farley, who had been Williams's football coach from 1987 through 2003 and still helped coach the track team. If anybody knew the story behind number 50, it would be Farley. Except he didn't. "I just knew we didn't give it out," Farley recalls telling Doyle. "When we ordered jerseys every year, number 50 would be on the list, and I'd just put a line through it. I assumed it was a fallen player, maybe in the military."

Not long afterward Williams played Wesleyan on Homecoming day on Weston Field. Quinn was filming Flip video of the game while standing on the sideline. Doyle approached him and said, "Do you know there's a retired number in Williams football?"

"Williams doesn't retire numbers," Quinn replied.

"Apparently it does," Doyle said.

On the Monday after that game Quinn called Boyer and asked, "Williams has a retired football number?"

"I don't know about retired," Boyer said, "but there's this box down here."

Quinn walked across the campus from his office in Hopkins Hall to Boyer's equipment room. Boyer showed him the box, and Quinn opened it. Inside were three tightly rolled football jerseys, stiff but otherwise well preserved. Two were white and one was purple. All were number 50. By the time Quinn arrived back in his office, the photos he had requested had been e-mailed from the archives: black-and-white portraits of a handsome kid wearing jersey number 50. In one of them Mike Reily smiled back at him. The jersey trim seemed to match that of the ones Quinn had just pulled from the old, tattered box. Quinn thought: Number 50 is Mike Reily.

Fall 1960: The big cat

A freshman class of 288 students entered Williams in the fall of 1960. They were all males (the college would not accept women for 10 more years but is now 52% female), almost all white and largely from privilege. They arrived in a time of fading innocence, still tethered to the Elvis and Buddy Holly '50s but very much on the precipice of change. "I spent four years at Williams and never heard anybody mention marijuana," says Chris Hagy, 69, who graduated in the class of '64 and is a federal judge in Atlanta. "I came back to visit the next year and everybody was talking about marijuana." The civil rights movement was nascent. Vietnam was a distant rumble that had not yet affected most U.S. campuses.

The Heart Of Football Beats In Aliquippa: Hope and despair in a Pennsylvania mill town

Like most of his classmates Reily was rich, white and clean-cut, but in some ways he stood out: not just tall but also broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted, with a Southern drawl and an easy confidence. "He had a big cat's physical serenity, with a big cat's action, not just athletically but every day too," recalls Joel Reingold, then a hockey goalie from Newton (Mass.) High. "He was sophisticated, with that New Orleans thing. His voice sounded like burnt sugar, man, like burnt sugar. All the girls who came to the campus wanted to date him, and that made him a quasimagical figure. All the guys wanted to be in his circle, and it was a big circle. He was the alpha male."

Yet to a Southern kid about to turn 18, Williams must have seemed a cold, distant and isolated place, dominated by boys from prep schools such as Exeter, Andover and Choate. Reily was born in 1942 into the upper crust of New Orleans society, the second son of James Weaks Reily Jr. and Leila Manning. James, whom everybody called Jimbo, ran the family's lucrative coffee firm, Wm. B. Reily & Co., for a number of years and rebuilt a flagging electrical supply company after that. He and Leila, who was known as Lee, had four boys: Patrick in 1941, Michael a year later and, seven years after that, twins Tim and Jonathan. The Reilys lived in a big white Victorian on Valmont Street in Uptown and shared the family's 200-acre vacation compound an hour north of the city on Bayou Liberty. All the kids water-skied like mad, and most of them could balance on a wooden disk, spinning it while holding a tow rope. "But Michael was the only one who would put a chair on the disk," says Tim Reily. "He'd stand up on the chair, on the disk, and ride by. That's the kind of athlete he was. He was the star of the show."

In New Orleans, Patrick and Mike lived hard, fast and generally beyond their years. By their mid-teens they were regulars at Pat O'Brien's bar in the French Quarter and Bruno's Tavern in Uptown, near Tulane. "Both my mother and father tended to drink and party a little bit too much, and we were probably an impediment to that, so we had a lot of freedom," says Patrick, 70, a retired lawyer in Miramar Beach, Fla. "We were in the French Quarter at 14. The legitimate drinking age was 18, but nobody was carding anybody." Family photos capture the moments, boys playing dress-up in dark suits with skinny ties, beers in hand and pretty girls nearby.

They called themselves and their friends the Krescent City Krewe, and while Mike was not the oldest in the group, he was the leader. On a crazy weekend in 1958, Mike rode with 18-year-old Joe Carroll in Carroll's '51 Ford Victoria from a party in Pass Christian, Miss., to Key West and then took the ferry to pre-Castro Cuba. "You had to be 18 to get on that ferry, and Michael was only 16," says Reily's cousin Larry Eustis III. "But Michael looked older and acted older, and he just talked them into it."

In the fall of 1955, Mike had been shipped off to Woodberry Forest (Va.) School, where he became a star football player, wrestler and track athlete and prefect of the senior class, the highest honor bestowed on a student. Woodberry's big football rival was Episcopal High School, and by the autumn of '59, when Mike was a senior, Woodberry hadn't beaten Episcopal in 13 years. That streak ended when Mike, playing tight end, caught a game-winning 67-yard touchdown pass from quarterback Charlie Shaffer. It's a famous play in Woodberry history but not the play that Shaffer remembers best. Early in the game Episcopal ran a sweep to Mike's side. "Mike delivered the most bone-crushing tackle I'd ever seen or heard," says Shaffer. "It was a play that made all the young guys on our team feel like we could compete."

In the spring of their senior year Shaffer and Reily were offered Morehead Scholarships, academic-based grants that would pay four years' room, board and tuition at North Carolina. Both young men were also recruited to play football for the Tar Heels. Shaffer accepted, but Reily declined, having decided to attend Williams. His siblings are still flummoxed by the decision. North Carolina was big and Southern, with Division I sports. Williams was Northern and stodgy, with small-time sports. "Maybe he wanted to get away from all the partying and drinking," says Patrick Reily, "but he could have gone to Chapel Hill for free. Our father had a lot of money, but he held on to it. He would have taken it all with him when he died, if he could have."

Shaffer blew out his knee as a freshman quarterback but was such a skilled athlete that he switched to basketball; he played on Dean Smith's first three teams and was the Tar Heels' co-captain in 1963-64. "I so wish that Mike had accepted the Morehead," says Shaffer, 69, who spent 36 years as a trial lawyer in Atlanta. "He would have been a great football player at North Carolina, there's no doubt. He could have played at a much higher level than Williams. But I think he wanted to reach for the stars in sports and academics."

Reily was surely the best player at Williams. He became the starting center and inside linebacker in 1961 on the first day of sophomore practice. (Freshmen were ineligible for the varsity.) Assistant coach Frank Navarro, 31, ran the defense for Len Watters, who was 63 and would retire after the following season. Navarro installed a 5-2 "monster" defense, modeled on Oklahoma's 52 scheme. Vital to the defense was the strongside linebacker, Reily's position. "That linebacker ran free," says Navarro, now 81 and retired. "He had to call the defense, read the play and make a hit in the backfield."

Reily filled the role brilliantly. In a preseason scrimmage the Ephs battled Dartmouth on even terms for more than two quarters, and afterward Big Green coach Bob Blackman expressed disappointment that an athlete as talented as Reily didn't wind up in Hanover, N.H. Reily would finish his sophomore season with 89 tackles in eight games, then a school record, but it was the force of those tackles that teammates would remember. Bill Holmes, a junior end in '61, recalls that in the Amherst game he grabbed a running back around the ankles and hung on to a foot. "Then there was this tremendous force transmitted down the guy's body, and it was Mike Reily just clobbering him," says Holmes, 70 and a recently retired physician. "As we're getting up, Mike says, 'Nice tackle, Willie.'"

Reily and those '61 Ephmen were never better than on that day against Amherst, which was not only Williams's rival but also unbeaten and ranked the No. 1 small college team in the East. The annual Williams-Amherst game, which will be held for the 126th time on Nov. 12, is as vital to the players and alumni of both schools as Auburn-Alabama or Harvard-Yale is to theirs. ("Sixty minutes to play, a lifetime to remember," Farley would tell his players years later.) On this day Williams, 5-2 going in, upset Amherst and its cutting-edge Delaware wing T offense 12-0, holding the visitors to just 63 yards on the ground and three pass completions.

Film of the game reveals Reily as a dominant force, easily flowing to the ball, making nine tackles, intercepting two passes-one inside the Williams' 10-yard line and recovering a fumble. Reporting on the game for The Berkshire Eagle, Williams senior Dave Goldberg wrote, "Reily, who in a year of varsity play looks like one of the best linemen in Williams history, was all over the field."

In a snapshot after the victory all 32 Williams players stand in front of the school bus that would transport them from Weston Field to Cole Field House. Reily, the defensive star of the game, is hiding in the back row, far to the right, giving seniors the moment. Surely he would have his time.

Winter 1963: "Incurable"

After the 1961 season Reily was named to the Associated Press All-New England Team and was a third-team small-college All-America. A year later Williams again went 6-2, and it allowed just 25 points in eight games. Again Reily was All-New England, though years later his teammates would recall ominously that while he was good, he wasn't quite as good as he had been in '61. On campus he had moved into a room in the Alpha Delta Phi house; Williams was dominated by fraternities, and AD was the jock house. As a freshman and sophomore Reily had driven around on a Triumph motorcycle that everyone remembers as his but in fact he'd bought together with classmate John Winfield. "We used to ride on it together up to Bennington, looking for dates," says Winfield, 69, a practicing physician and retired professor of medicine.

As a junior and senior Reily had a '63 Jaguar XKE. Often he took Navarro's nine-year-old son, Damon, for rides in the countryside. Once, on a whim, he hopped into the Jag in Williamstown on a Friday afternoon, drove to New York City and flew with roommate Bill O'Brien to St. Croix for the weekend. And Reily did not retire his drinking shoes. "He liked to party," says Bruce Grinnell, 71, senior quarterback of the Williams '61 team, "but he was always under control. He was the Big Kahuna." Friends say Reily also excelled in the classroom as an English major and planned on a future in banking.

In The Nick Of Time: Alabama's football faithful welcome their savior

He embraced his popularity without flaunting it. "Handsome and gregarious, yet humble and charming," says Winfield. Once, in the sitting room of the AD house, a regal three-story yellow-brick building in the middle of the campus (with a Coke machine that served up beers), junior Max Gail was emotionally arguing a point that he now can't recall. When the discussion broke up for dinner, Reily, by then the president of the fraternity, said to Gail, "You make up your own mind, don't you? I really respect that."

"Mike had a kind of depth to him," says Gail, 68, who later achieved pop-culture fame as Det. Stan (Wojo) Wojciehowicz on the TV comedy series Barney Miller (1975 through '82). "Knowing him was one of the most powerful experiences of my life."

One morning in the winter of 1963, Williams junior and AD member Jack Beecham was awakened by violent coughing in Reily's room. Reily didn't come to breakfast and wasn't seen for a few days after that. Soon after developing the cough he went home to New Orleans.

Patrick Reily was there when his brother came home. "He went to the doctor here, they did a chest X-ray, and they found a growth of some sort," says Patrick. Mike's chest had to be cracked open so the mass could be biopsied. "He started getting treatment," Patrick continues, "and then one day he came home and opened up this encyclopedia we had on the coffee table. He tapped his finger on the book and said, 'That's what I've got.' I asked him how he knew for sure, and he said, 'Nobody told me, but I looked at my chart at the treatment center.' He was pointing to Hodgkin's disease. I remember it said, Incurable. Life expectancy one to two years. Then I remember Michael just walked up the stairs."

Hodgkin's disease, a cancer of the lymphatic system discovered in 1832, has become one of the most curable of cancers, with five-year disease-free survival rates as high as 98%. Had Reily developed Hodgkin's as little as four years later, his chances for survival would have been much better. But in the winter of 1963 he was facing a deadly illness.

He was treated with radiation -- "They just cooked him," says Gage, 69, a surgeon in Pensacola, Fla. "That's what radiation was at that time" -- and then with intravenous nitrogen mustard, a chemical warfare agent that is regarded as the first chemotherapy agent. It was very effective at killing cells but brutal on the infected individual. As soon as treatment started, Reily began to deteriorate.

He also made the last important decision of his young life: He would spend his final months as he had spent the previous 2½ years. "I asked him what he was going to do," says Patrick. "I would have gotten drunk in every bar on earth. Michael said, 'I'm going back to Williams for the rest of my junior year, and then I'm going to graduate. I'm going to spend time with my friends and my family. Those are the most important things in my life.'"

A little more than a month later he returned to Williams and told O'Brien the same thing. "I asked him if he was tempted to just get in the Jaguar, take off and have some fun," says O'Brien, 71, who would spend most of his adult life as a lawyer. "We all think of that, right? What would we do if we had a year to live? He said, 'What would I accomplish by doing that? I owe it to a lot of people to finish this out.'"

Reily gathered up a bunch of AD buddies in the house kitchen one night and told them he was sick but never said he was dying. They figured that out on their own. "He would show up in class wearing shirts with 18-inch necks," says Dan Aloisi, 68, a football teammate and later a successful entrepreneur, "except his neck was only 15 inches."

There was a girl. In Reily's life there had always been girls. "They could have filled the church at his funeral," says his younger brother Tim. But this one was special. Sandra Isabella Skinker, who had been a cheerleading co-captain at Summit (N.J.) High, was tall and blonde and smart. She was in the class of 1963 at Skidmore, then an all-women's college, an hour away from Williams in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. Skinker, now 70 and living in Vermont as Sandy Bennett (her married name, though she is divorced), had dated O'Brien, but they drifted apart in the spring of '62, and that fall she and Reily, who were already close friends, began dating. (She was with Reily the morning he awoke coughing, and she watched him spit mouthfuls of blood into a frat-house sink.)

"Football players could be so full of themselves, but Mike was such a warm and caring person," says Bennett. "And he had this irreverence about himself. I had never known anyone like him." In the spring of 1963, even as Reily began to suffer the effects of treatment, they met up in the Bahamas, where Sandy had gone with her parents and Mike with his mother and some AD guys. "We all had great fun," says Bennett, "but we all wore rose-colored glasses. Mike was already beginning to look tired, his eyes were sunken." He and Sandy danced together to Autumn Leaves, and as they swayed to the music Mike said, "I hope I live to see another fall." They had talked about a life together, but shortly before her graduation from Skidmore that spring he sent her away. "He told me, 'I wish it could work out for us,' " says Bennett, "and he told me he loved me. But he said, 'I don't want you to watch me disintegrate.'" They cried together. They would never see each other again.

In the summer of '63, Reily visited Chapel Hill. After a party there, a woman named Bonnie Hoyle spoke to Reily and expressed her sympathy for his condition, but Reily told her not to feel sorry, saying he had experienced more in his short life than many people who live much longer. "I will always remember that night," she says, "and the peaceful look on Mike's face." Nearly a year later, in the spring of 1964, Shaffer would ask Reily to be in his wedding that summer. Reily said yes, but surely knew he wouldn't make it.

Reily had two goals left that fall: to help captain the Williams football team and to graduate. He returned to the Berkshires in the late summer of '63, gaunt and burned by radiation, unable to put on pads. Watters had retired, and Navarro, at 33, had been named coach. After an early practice Navarro gathered the team on the Cole Field practice grass and told them, "Mike won't be able to practice, but he'll be here every day with us." Reily wore gray sweats and a helmet every afternoon, the best athlete on the field helping to lead calisthenics drills and hold tackling dummies.

It was a Williams tradition for players to sprint up the steep hill to Cole Field House after practice, and Reily would join his teammates in that effort. "He'd get to the top of the hill, snap his helmet off and start coughing and spitting," says Aloisi. "He just couldn't take it." Aloisi would later do a tour in Vietnam with the Marines and says, "Mike faced a terminal illness the same way my buddies faced combat. He faced it head-on, never looked for sympathy and led the team to the best of his ability. It was incredibly inspiring." Every Saturday, Reily would join Wagner at midfield for the pregame coin toss and then take a spot on the bench, where he would listen for the coaches' defensive signals on headphones.

During that senior year, in which the Ephs went 2-6 and lost to Amherst 19-13, Reily was a ghost among his peers, often spending long stretches in the college infirmary. He would wear a parka in class because he was frail and cold. His roommate on the third floor of the AD house was Dave Johnston, now 69 and a general surgeon in Jacksonville. Late at night, alone in their room, Reily would ask Johnston, "Johnny, what do you think about dying?" It was a difficult topic for Johnston to discuss. "I'm 21 years, I'm omnipotent," recalls Johnston. "I didn't want to talk about dying."

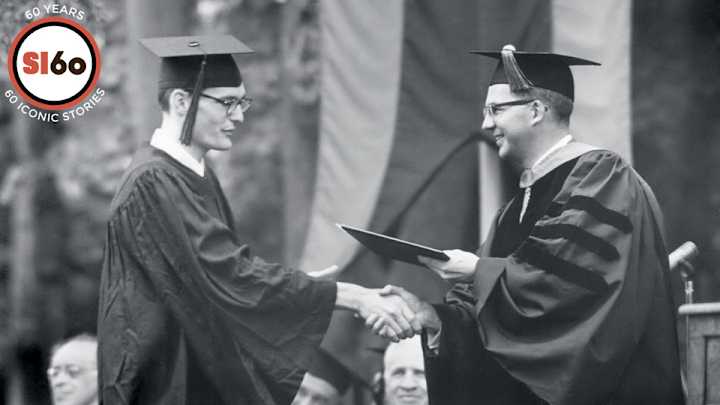

On Sunday, June 14, 1964, Reily put a cap and gown over a white dress shirt and tie for graduation in a field called Mission Park, behind the Williams Hall dormitory where he had lived so large as a freshman. He sat in a folding wooden chair as U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk delivered the commencement address, warning of a military escalation in Vietnam. Reily's parents, divorced by then, sat in the audience.

Joel Reingold, who had so worshipped Reily four years earlier, sat next to him at graduation. "He coughed throughout the ceremony," says Reingold. "This magnificent specimen, reduced to almost nothing. He kept saying, 'I just want to graduate, I just want to graduate.' Then he walked up there and got his diploma, and when he got back to his seat he was exhausted. It was so heroic. We were all young, and we felt strong. We didn't know the war was coming, we didn't know the world was about to change. And here was Reily, the best of us, doing this one beau geste. It was incredible."

When the ceremony ended, the graduates marched joyously out of the makeshift stadium. Jack Beecham looked off to the side and saw Reily standing in a grove of pine trees. "He was looking at all of us parading past, smiling and happy," says Beecham. "He looked to be alone. And he had this sadness on his face, that I think only an awareness of impending death can bring."

On a late spring afternoon nearly five decades later, Big Ben Wagner sipped an iced tea on the porch of a seafood shack on the New Hampshire coast. "After that day, we scattered to the wind to make our mark on the world," he said. "Mike went home to die."

November 1963: The jersey

At the end of each football season the Ephs' coach would meet with his equipment manager, and they would go through the jerseys and make a list of those that needed replacing. The coach would then place the order with visiting Champion salespeople and later walk the list down to a store on Spring Street. So it was that after the season-ending loss to Amherst in '63, Navarro stood in Cole Field House as the jerseys were laid out one by one, in numerical order. When Reily's number 50 was spread on the counter, Navarro recalls, the equipment man asked, "What should we do here?"

"We decided, let's put this thing away for a while," says Navarro. "Let's just put it away and not order it." The equipment man rolled up Reily's three jerseys and put them in an empty red, yellow and white football box and wrote on two sides the imperative that Joe Doyle would notice 47 years later.

What Is The Citadel? For some athletes, it was a place of nightmares

It will probably never be known for certain which equipment man wrote the message that endured so long. When first interviewed by SI last spring, Navarro said it was Jimmy MacArthur, who had started work at Williams in 1937. MacArthur, born in 1892, was a courtly gentleman with a full head of silvery hair and just a thumb and index finger on his right hand. He was closer to the players than the coaches were, recalls Navarro, who would occasionally ask, "Jimmy, how are the boys doing today?" MacArthur died at 72 in July 1964, the same month as Reily. His obituary in The Transcript of North Adams, Mass., noted that he had retired two years earlier, which means that he shouldn't have been the man who put away Reily's jerseys (though members of the Williams teams of '62 and '63 recall frequently seeing MacArthur around the equipment cage after his retirement). Navarro, on being told this, backed off on his assertion that it was MacArthur who put the jerseys away. "Maybe we shouldn't say for sure," said Navarro, who would be a college head coach for 22 years and raise eight children with his wife, Jill. "Maybe it was Charlie."

That would be Charlie Hurley, who joined MacArthur in the cage in 1958, at age 50, and worked at Williams until 1973. Hurley served as a corporal in the U.S. Air Force in World War II and worked at clothing stores in North Adams and Williamstown before coming to the college. If he didn't put Reily's jerseys away, he surely protected them from 1964 to '73, as the Williams coaching reins were passed from Navarro to Larry Catuzzi in 1968 and from Catuzzi to former Maxwell Award winner Bob Odell in '71. With Hurley, the pattern was established, and a succession of equipment managers -- most of them working-class men arriving at Williams from other jobs and other careers -- simply read the writing on the box and obeyed it.

and died in 2000. He never gave out number 50.

But he did something else. In 1977, when his North Adams neighbor Joe Janiga was out of work after many years as a salesman on the floor of a furniture store, Murphy arranged for Janiga to become his assistant at Williams. Murphy was quiet, and Janiga was a ballbuster. "My father loved working for that college," says Janiga's daughter, Diane Simpson. "He loved the students." They loved him too. For many years Bill Keville and Bill Haylon, Williams athletes in the class of 1981, would conference-call Janiga at his home around the Christmas holidays, and that call would make Janiga's day. He died in 2007. He never gave out number 50.

Dick Cummings was a local legend, a man-among-boys running back at Williamstown's Mount Greylock High in the late 1960s and a 250-pound fullback at UMass after that. He spent a decade in Colorado working underground in mines and then came home and was hired by Williams to work with Janiga. He found a small, empty, gray metal recipe file with Mike Reily's picture taped to the top, except that he didn't know who it was. Cummings still works at Williams, in the basement of the gymnasium, back underground. He never gave out number 50. He still has the recipe file on his desk, with Reily's photo still taped to the lid.

Dave Walsh came aboard after Janiga retired. He had been a Marine on Guadalcanal in World War II and then a police sergeant in Florida before moving with his family to New England in 1967 and taking a job as a Williams security officer. Two years shy of 65, Walsh was transferred to the athletic equipment room in 1985 and finished up there. Diminished in later years by Alzheimer's disease, he would still attend Williams football games, where alumni of a certain age would remember him fondly, even if he didn't remember them. Walsh died in 2009. He never issued number 50.

Finally there was Boyer. He was a baseball star at Drury High in North Adams and went to work on the assembly line at Sprague in 1979. He spent nine years on the soul-sucking job, but it was a paycheck. When Williams called after Walsh retired in '87, it wasn't an easy decision. "My wife was pregnant with our first child, and I'd be losing 50 cents an hour and a week's vacation," Boyer says. But he took the job and saw the cardboard box early on. In 2004 first-year coach Mike Whalen, who succeeded Farley, offered number 50 to a hot recruit. "He wore 50 in high school, so I thought he might want it at Williams," says Whalen, who in '10 left to become coach at Wesleyan, his alma mater, and was replaced by Aaron Kelton. "I went to Glenn, and he said, 'Sorry, we don't use number 50.' And that was it."

Boyer was there through a major renovation of Cole Field House in the winter of 1996, when everything was moved into a storage facility. The box came back out, battered but intact. "I looked at it all the time, but I never looked inside," says Boyer, 23 years on the job. "It just seemed like maybe there was something special inside."

November 2011: Homecoming

Mike Reily lived just 41 days after his graduation from Williams. He went home to a bachelor pad on Danneel Street in New Orleans, where he lived with his brother Patrick but was mostly confined to a bed and doted on by his mom. On Tuesday, July 21, 1964, Mike was transferred to Touro Infirmary, and four days later, at 1:40 on that hot Saturday afternoon, he passed away. The coroner would write on Reily's death certificate that his illness had "disseminated," meaning it was throughout his body. His remains were shipped to Houston for cremation, but there was a funeral, and the church was full of mourners.

Nearly 47 years later Patrick and Tim Reily are sitting with their cousin Larry Eustis at the kitchen table in Eustis's New Orleans home, telling stories about Mike, recalling the euphoric and the tragic, sometimes in the same sentence. There is a pause in the conversation, and Eustis removes his glasses to wipe tears from his eyes. "We've never talked about this," he says. "We just submerged it."

Tim Reily says, "When Michael died, he was never spoken about in our family. It was like he never existed. I think it was just too much, too painful." Jimbo is gone, having died in 1988. Lee went five years later. Patrick battled alcoholism (he's been sober for 19 years); Tim lost a teenage son named after Jimbo, a good young football player who reminded his father of Michael and died of a drug overdose far from home. In all of this, memories of Michael drifted away.

This was also true among many of the young men -- now old -- who knew Reily. He was frozen in their minds, forever young, and there was no closure, only an inexorable moving forward. Dave Johnston went through life wishing he had been more willing to talk about death when that's what Reily needed. (He was in Europe when Reily died, and Reily was supposed to have gone on the trip. Jimbo had been given orders by Mike to wait a week before calling Johnston, so he wouldn't ruin his vacation by rushing home for the funeral.)

Chris Hagy beat himself up for not visiting Reily in the infirmary during that long senior year. "I was young and selfish," he says. "Maybe I was scared that Mike's illness was the first time I learned I wasn't invincible."

Jack Beecham wished he had comforted Reily when he stood alone in that grove of trees after graduation, something he would do for dying patients many times in later years. "Of course I didn't know to do that," he says. "It took me years to learn how."

Sandy Bennett kicks herself for not staying with Reily when he told her to leave. "But 50 years ago," she says, "women just didn't do that."

Big Ben Wagner got cut late by the Kansas City Chiefs, went to Vietnam and captained a swift boat, came back and got his M.B.A., made some money and then went home to New Hampshire to help his dad and brothers run their apple orchard. Always he felt a nagging sense of incompleteness. "I was Mike's co-captain," says Wagner. "I felt like I had unfinished business with him."

A Flame That Burned Too Brightly: Hobey Baker found little to live for after starring at Princeton

So there is now a humbling power in a pummeled old box of jerseys and a photograph snapped so long ago. On Nov. 12, on Homecoming weekend, Williams will formally make Reily's 50 its first retired number, and it will also establish the annual Michael Meredith Reily '64 Award, to be given to the football player who, in the estimation of his teammates and the equipment manager, best exemplifies the qualities of performance, leadership and character. Teammates will be there, and family members too. Estranged for decades, the Reilys were brought together by a writer's query, and finally talking about Mike has helped them to heal. They drove together through New Orleans on a warm spring afternoon, past the hospital, the cemetery and the home where they once lived. There was laughter and silence too. Now, on one night in the Berkshires, stories will flow again. And tears.

There had been another ceremony, after Mike's funeral. His ashes were returned from the crematorium in a cardboard container, and his family gathered on a wooden footbridge on the bayou that Mike loved so much. Somebody said a quick prayer, and then Jimbo poured Mike's ashes into the water and weeds. "Nobody said anything about Michael," says Patrick. "My father just sort of threw the ashes out there, and we all walked off the bridge." This awkward, joyless image was all that was left for many years.

Now there will be much more: a celebration of spirit, a recognition of courage, and sweet, full memories of a short life fully lived.