The Sixth Man: Miami guard Ja'Quan Newton out to prove he is the best basketball player in his family

After Miami's 65–63 win over Pittsburgh on Tuesday, Hurricanes assistant coach Jamal Brunt asked Joe Newton what was supposed to be an innocent question: Who is the best player in the Newton household?

The 1998 NABC Division II National Player of the Year answered without hesitating. "Me," Joe said. But the player ESPN analyst Dick Vitale likes to call the best sixth man in the country overheard the conversation, and disagreed. "Me," said Ja'Quan Newton.

"I almost asked him to play me one-on-one right there in Miami, in front of his teammates and coaches," said Joe, who starred at Central Oklahoma before playing professionally in countries including Mexico, Colombia, Croatia and Greece for nearly a decade. "But I decided since they got the big win, I'd let it go for now."

Ja'Quan isn't fazed. "Last time we played one-on-one," he says. "I was in the eighth grade. He stopped it, said he had to 'be somewhere.' We haven't played since." Ja'Quan laughed. "He's scared now!"

Joe, who works part-time at the Philadelphia Convention Center, insists that isn't the case. At 41, he works out "excessively" each day, honing his game because he loves hoops but also because, "I can't let my son beat me!" He estimates that by the time Ja'Quan finishes playing at Miami in two years, he might be able to beat Joe, but not before that. He isn't ready to deem his son the best player in the family. But he's good with calling him the best sixth man in the country.

Jim Larrañaga agrees. The fifth-year Hurricanes coach calls it "a luxury" to go to his bench and get a proven scorer. Newton, a 6' 2" sophomore, averages 11.6 points and 2.6 assists per game and is Miami's highest-usage player (28.7% possessions) when on the floor. "He comes in," Larrañaga said, "and we get better."

Like many freshmen, Newton initially recoiled at the idea of coming off the bench. An RSCI top-50 national recruit in the class of 2014, he was used to being the man, he says, at Neumann-Gorett High in his native Philadelphia. But Newton came to Miami at the same time Kansas State transfer Angel Rodriguez became eligible for the Hurricanes and emerged as one of the top point guards in the ACC. Ja'Quan had no choice but to be a backup. Instead of pouting, he remembered advice from his father and his mother, Lisa Brown.

From his dad: Never be selfish. Never look down on anyone or hate on anybody because they have something you want. Wait your turn. From his mom: You get the respect you give—including to and from people in front of you in the rotation.

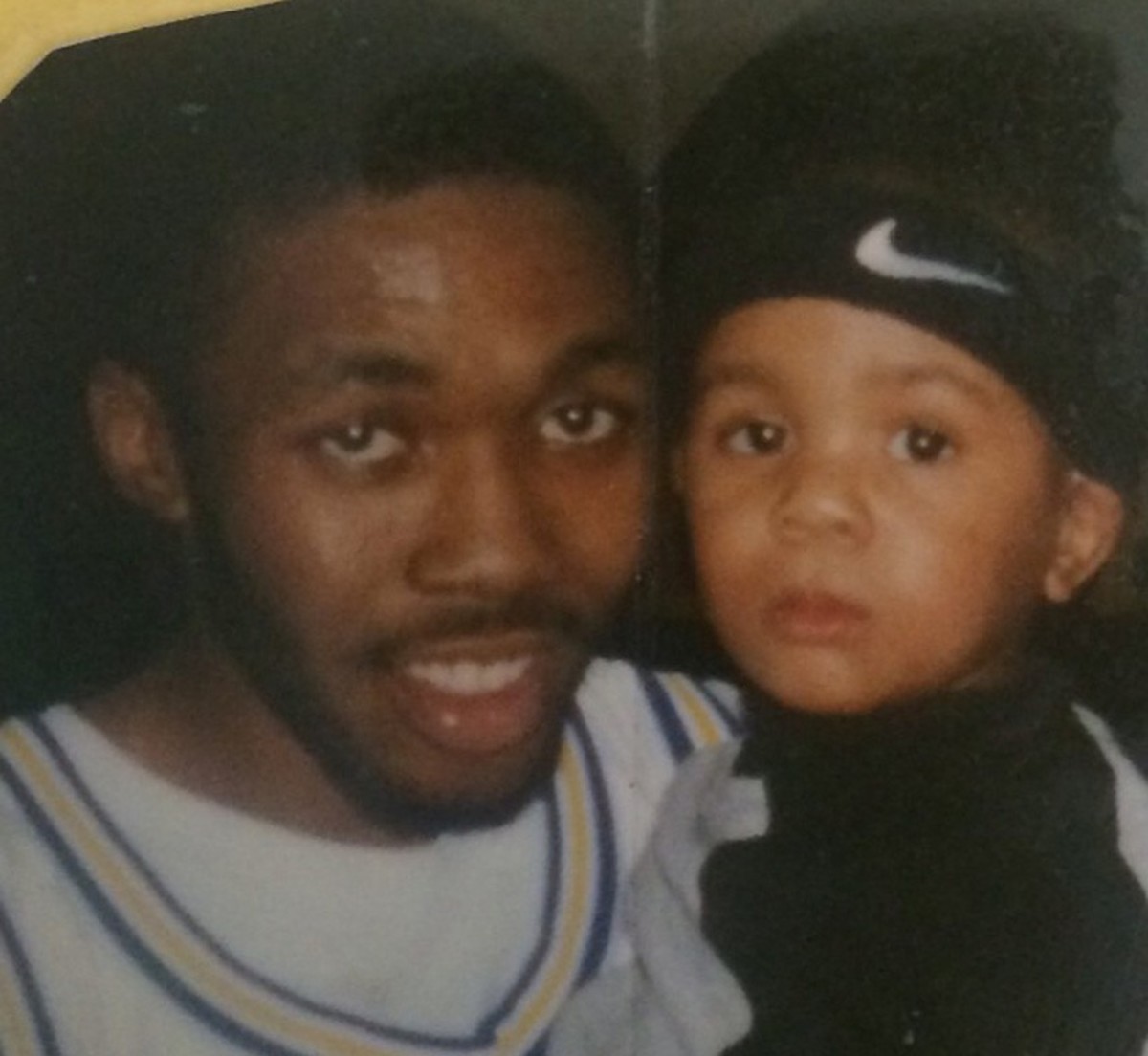

Courtesy Joe Newton

It's advice he still heeds. Through 23 games, Newton is second-leading scorer and assister for the 19–4 Hurricanes, who are ranked No. 12 in the AP poll. Years ago Joe told Ja'Quan that scoring early in games wasn't everything. Drawing from lessons he had learned watching Magic Johnson, Joe told Ja'Quan that involving teammates early usually meant they would go to battle with you late. Ja'Quan relishes his role as what Larrañaga likes to call a "multipurpose guard," increasing his scoring output (from 4.6 points as a freshman) and his shooting percentage (from 40.5% from the field last season to 48.6% now).

He just wishes Brown could see it.

During his senior year in high school, Ja'Quan traveled with his mother to Miami for an official visit. Brown had been diagnosed two years earlier with breast cancer and knew she would not live much longer. So she went to Liz Larrañaga, Jim's wife, and had a mom-to-mom conversation. "She basically asked my wife to take care of Ja'Quan," Larrañaga recalled. "She said, 'He needs a family—will you look after him?'"

Brown died months later, on March 20, 2014, at age 38, the day before Neumann-Gorett played for its fourth state championship game in Newton's career. He responded by scoring 33 points in a 64–57 overtime win, explaining afterward to local media that he knew his mom would be up in heaven "fussing" if he used her death as an excuse to quit. Ja'Quan says now that decommitting to stay closer to home, and his remaining family, never crossed his mind. In Coral Gables he found two things his parents had wanted for him: safety and sunshine. Joe says in the part of Philly where Ja'Quan grew up, "coming out of your house and walking to the corner store is dangerous." They all knew basketball was Ja'Quan's way out. Brown never had to tell Ja'Quan to leave. He always wanted to go.

"In Miami, I don't have to worry about anybody trying to hurt me," Ja'Quan says. "In Philly, I saw a lot. I saw one of my closest friends get killed in a drive-by shooting; he didn't do anything, just walking down the street. Growing up, all I thought about was, 'I don't want to keep watching the same thing over and over.' In my neighborhood, they're not going to let anything happen to me, I go somewhere and people always have my back. But people come in from other 'hoods, other towns, they're the ones who try to hurt you, because they're jealous. They don't want you to succeed."

Ja'Quan says that sometimes the attitude is, If I can't find a way out, then why should you be able to?

Still, he credits his upbringing with molding him into a college basketball player. Known for some of the best pick-up basketball in America, Philadelphia has churned out some of the premier players in college and professional hoops. In South Philly, Ja'Quan played regularly against Samir Doughty, now at VCU, and Maurice Watson Jr., now at Clemson.

He isn't sure who placed a basketball in his hands first, but Ja'Quan's earliest memories are tagging along with Joe to pick-up and rec league games, bouncing a ball on the sideline as his dad "put on a show." Joe was always one of the best players on the court, Ja'Quan says, and he watched closely as his dad relentlessly attacked the rim, blowing past defenders with change-of-pace moves.

Ja'Quan started with Nerf hoops and kiddie balls, with Joe watching him and correcting his form. When Ja'Quan's turn came on the pick-up courts, Joe told the other adults—Joe says he never let Ja'Quan play with his age group—not to take it easy on his son. "They'd foul me, push me down. They never asked if I was O.K., just always yelled, 'Get up!'" Ja'Quan says. "At first, I'd get mad, because I couldn't score. I'd be like, 'Man, what the hell? What is going on?' But it made me tough."

Ja'Quan spent hours in the gym, dribbling around cones and chairs with Joe barking out instructions about when to cross over, when to hesitate and when to go between the legs. One screw-up sent Ja'Quan back to the start. In the eighth grade, dad would wake son at 5:30 a.m., drive to the gym for drills, bring him back in time to shower and then send him off to school. "A lot of people thought it was too much," says Joe, who split with Lisa when Ja'Quan was 14. "Now they see him, and they know it paid off."

As Ja'Quan readies for what he expects will be a deep postseason run, he keeps both his parents close. He prays to Lisa before each game, asking her "to help make the basketball go in the hole," he says. If he gets hot, he believes it's because she was listening closely that night. After every game, Ja'Quan heads to his locker to check his text messages, anxious to read Joe's takeaways. It's a mix of good and bad, praise and criticism. Sometimes it's trash talk, too. Because as good as his son is, Joe Newton can't relinquish the title of best player in the Newton house just yet.