Far from Hollywood, the life of Charles Gitonga Maina is a complicated tale

It’s six miles from Jomo Kenyatta International Airport to the Nairobi neighborhood of Buruburu, but the drive, in a city with only a couple of working stoplights for 3.9 million residents, can take several hours. This leaves plenty of time for my driver to ask why I’ve traveled halfway around the world for only a weekend. It’s a good question.

I first tried to track down Charles Gitonga Maina, Kevin Bacon’s costar in the 1994 film The Air Up There, two years ago when I was coordinating producer of the short-lived Fox Sports 1 show Crowd Goes Wild. We’d had success bringing on former stars of much-beloved (if critically pilloried) sports films from the 1990s, when the form was at the height of its popularity. The surprising success of A League of Their Own, The Mighty Ducks, Rookie of the Year and Cool Runnings had made it easy for studios to green-light variations on the theme.

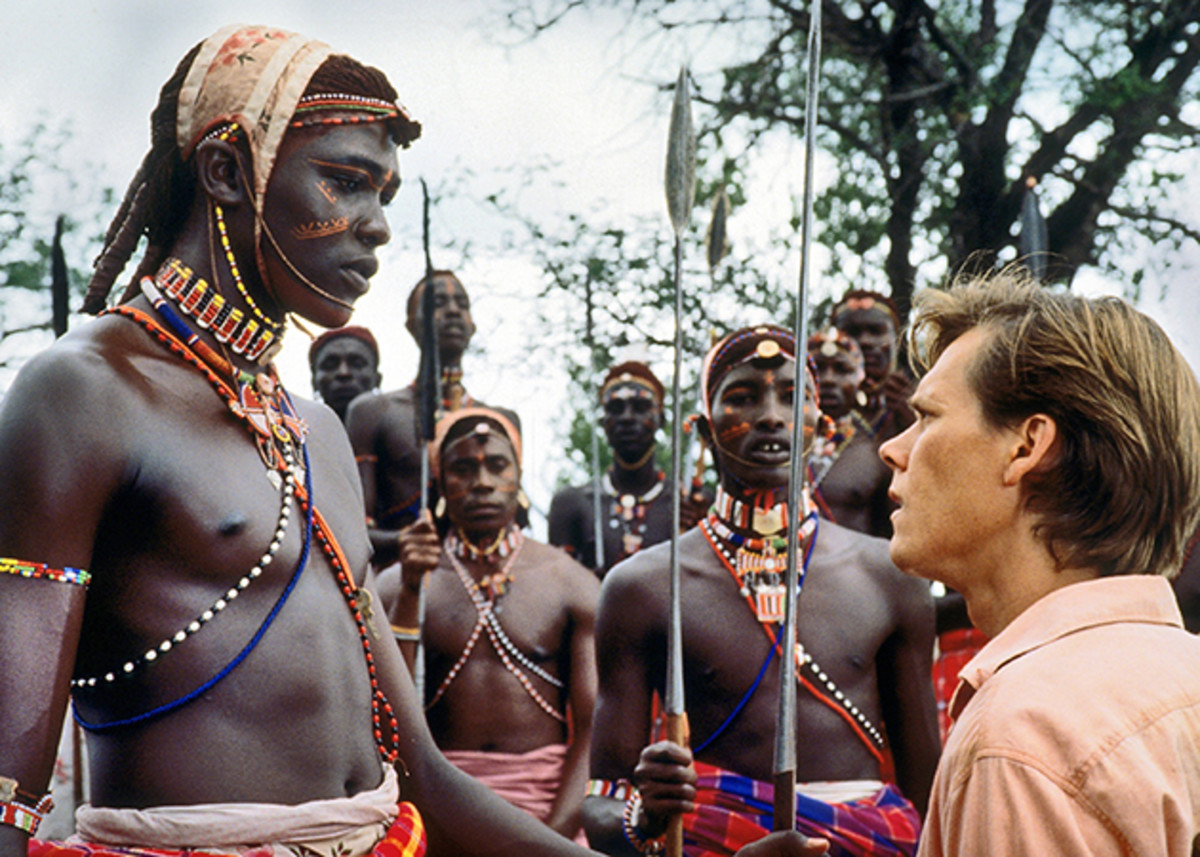

Lost in that mix was this basketball film of questionable substance. Bacon played Jimmy Dolan, a college assistant coach who, in a stroke of drunken inspiration, heads to a distant African village to win over the natives and land his next big recruit: the 6' 9" Saleh, played by Maina, who himself had been discovered in Nairobi by a foreign scout. Art imitated life, so to speak.

For all its faults, and there are many, The Air Up There exudes a certain charm. Maina, who was an 18-year-old novice actor when the film was shot, was almost unanimously praised for his portrayal of Saleh, a tribal prince. Critics called him “warmly appealing” and “hugely engaging.” And The Air Up There looked outward at the precise moment that basketball was becoming a global game. Six months after the movie was released, Nigeria-born Hakeem Olajuwon led the Houston Rockets to the first of two straight NBA titles.

Like many who came of age in that era, I was enamored by the NBA’s international turn, and Maina personified my childhood fascination. I couldn’t shake his story. So last fall, I decided to pick up the trail.

“I need to find someone,” I tell the driver. Nodding, he asks, “Where in Buruburu?” Another good question.

In today’s interconnected world, it’s nearly impossible to disappear. On any given day more than a billion people sign in to Facebook, or otherwise leave their mark online, making it easy for former classmates and meddling journalists to track them down no matter where they live. But Maina seemed to have vanished. My intel on his whereabouts consisted of a single Facebook post. After years of my badgering friends with experience working in sub-Saharan Africa, my sister, through a contact, returned with a solitary clue: “The guy can be found at the Buruburu shopping center.” I was told to check the bars first.

My plan was as simple as it was ill-conceived: Enter a bar in the shopping center, see if there were any 6' 9" patrons, and if not, move on to the next one. How many could there be?

“Five,” said the driver, David Muiruri, my mercifully patient 52-year-old Kenyan guide.

Buruburu is a middle-class enclave on the outskirts of Nairobi. The buildings are low, but mostly well made. The beating heart of the neighborhood is a dirt square that a stream of traffic funnels into, ringed with bars and filled with vendors and tradesmen. Its bars and cafes are popular weekend destinations where one can waste the hours away in a sea of local lager and English Premier League matches. Buruburu is not exactly a place for foreigners, who tend to land in Nairobi and head straight for their safaris, but it’s not unwelcoming either.

Maina was born and raised here, the third of four children of a telecommunications auditor and a nurse. He learned to play basketball at age 14. In 1991 he won the Nairobi slam dunk championship, and a year later he was chosen from among 46 other players at an open casting call for the part of Saleh. Director Paul Michael Glaser has said Maina won the role in part by boasting, during his taped audition, “I’m a dunkaholic.”

After we park, David and I approach the patio of our first bar, the Winds Club. It’s just after 5 p.m., and the sun has mercifully begun its retreat. When the waiter comes over, David takes the lead. No, the waiter doesn’t know any former actors or basketball players. We decide to have a round and then move on to the next place.

Once our beers arrive, a middle-aged gentleman who has been watching us from a nearby stool calls over in Swahili, “Ninamjua yule mrefu?” (“I know him, the tall guy?”) The man introduces himself as Benson, the local police chief, and sends a nearby teenager off in pursuit of the tall guy. We chat idly over another round. It can’t possibly be this easy.

Less than 10 minutes later, in this city bigger than Chicago, Charles Gitonga Maina ambles into the bar and asks if someone was looking for him. I awkwardly shake his hand and try to explain why I’ve come. We’re both overwhelmed. “Boy, do I have a story for you,” he says, his speech slightly slurred.

We agree to meet the following morning. Before Maina departs, Benson pulls him aside and whispers something into his ear. Later I ask what he said. Benson replies, “I told him to arrive sober.”

*****

When we meet the next morning, Maina is wearing a knitted beanie pulled low over his ears, no matter that it’s December and the temperature is in the 80s. When he finally takes it off, a receding hairline and a frosting of gray better reveal his 42 years.

We start from the beginning. He tells me that when he traveled to Los Angeles for the final audition for the movie, it was the first time he’d left Kenya. “My parents didn’t believe me,” he says. “I told them I was flying out and they said, ‘Where you going to?’ ” After he was picked up at the airport in a limousine, the driver chastised him for standing up through the sunroof. “I’m like, ‘I haven’t seen the world yet!’ ” Maina says.

Once he won the part, it was off to Hoedspruit, South Africa, where most of the filming took place. The cast and crew would become remarkably close over the three-month, $19 million remote production. Caterers served up to 2,000 meals a day to the more than 200 crew and 500 extras. Several people involved described the shoot as a family affair.

Excluding Bacon, who needed a stunt double for some of his dribbling scenes, the production included a veritable who’s who of hoops. The film’s technical advisor was former NBA MVP Bob McAdoo. Ilo Mutombo (Dikembe’s older brother) played Maina’s principal on-court adversary. Nigel Miguel, a former UCLA standout who had appeared in White Men Can’t Jump, played Maina’s older brother.

At 18, Maina was the youngest of the group, and his potential was obvious from the start. “When I first saw him play, I thought he had a chance to play college basketball in America,” says McAdoo, now a scout for the Heat. “Just seeing his enthusiasm and his size, I knew there was something there.”

“He was just a sweet kid, and that’s what was needed for this character,” remembers Miguel, now the film commissioner of Belize. “I don’t truly think he knew what he had accomplished.”

The movie had only modest success at the box office, but to many who saw it, it was oddly memorable. According to Miguel, former stars such as Allen Iverson and Michael Jordan have mentioned the film over the years, but it’s Shaquille O’Neal, playing to type, who likes to quote some of the more memorable lines (“I play for Wanabi!”).

Once the frenzy of the promotional tour subsided, Maina stayed in the States to pursue college opportunities. He bounced around junior colleges in North Carolina, Kansas and Florida before McAdoo, who was letting Maina stay with his family, called Jeff Price, head coach of Lynn University in Boca Raton, Fla., and asked him to take a look at a very raw but promising prospect. The result was a scholarship at the D-II level. This time, life imitated art.

Maina flourished. On the court he was the starting center and a key contributor for a team that made the NCAA D-II semifinals during the 1997–98 season, and he still holds the school record for blocks in a game (11), set in his second season. “His timing and ability to block shots was as good as any kid I’ve coached,” says Price, who’s still with Lynn. Yet throughout Maina’s two seasons in Boca, the shadow of Saleh loomed large. The local press couldn’t believe its good fortune. (Sample lede: “The real life story of Charles Gitonga Maina may end up a sequel to the movie.”) “We’d go on the road, and everybody knew who he was,” recalls Price. After his two years of eligibility were up, Maina considered his options. Acting had offered few opportunities since his leading role. “He’s 6' 9", and that was probably the ultimate hindrance to his career,” remembers Pearl Wexler, his film agent at the time. “This is a tough business when you don’t fit a certain mold.”

Instead Maina looked into a pro basketball career in Europe. McAdoo urged him not to go: “I went overseas. I saw what those European teams did to foreign players if they didn’t produce—they’d discard you like paper in [the] garbage.”

More concerning to McAdoo was that if Maina didn’t make a team, he could easily have visa problems and find it hard to get back into the U.S. But Maina had routinely defied the odds. Playing in Europe was the obvious next step.

Following the advice of his sports agent, he traveled to Greece for a tryout with a pro team. It did not go well, and Maina declines to tell me the details. Afterward he was denied reentry to the U.S. and forced to return to Kenya. It was the last time his American friends, coaches and teammates heard from him.

*****

What was it like after coming back?” Maina asks, anticipating my next question. He speaks theatrically even though it’s been at least a decade since he last told his story. “Lot of friends, you know how it goes. Suddenly you’re young and you have money. You’re asked to give, and you don’t know how to say no.”

Maina, now living at home with his parents, is a constant presence in the small Bermuda Triangle of bars in the Buruburu estate. He tends to speak in contradictions. He says he freelances in foreign currency exchange markets from a nearby Internet café, but he hasn’t checked his email or social media accounts in years and doesn’t have a cellphone. He helps coach young kids from the neighborhood, but he doesn’t own a basketball.

Then there are some realities he can’t avoid, like the scars. In March 2003, Maina was walking home one night when he passed two young men in the street. He said hello; they told him to empty his pockets. Suddenly there was a knife. “While one of them stabbed me, the other slapped me over the head with a stone,” says Maina.

Maina survived and spent three weeks in a hospital with a broken jaw, among other injuries. A few years later he contracted tuberculosis. He calls this his lowest moment, when a dark cloud entered his life. “I’ve been struggling with depression, I can’t deny it,” he says. “You expect your life to be here, you go downhill, you come back up, it continues.”

His neighbors are unsure of what to make of their once-famous son. They wonder what happened and why he’s been forgotten. Few know he starred in a Hollywood film; his golden ticket was the basketball scholarship, a chance to start a new, better life in a land of opportunity. That weight is heavy. And as the tallest man in town, Maina can’t hide from it.

“People have the conception that if you go to the States, Wow, you’re going to make it,” he tells me. “Little did I know, life is the same every-where, but with a different angle.”

At the end of each of these admissions Maina is careful to follow up with a platitude. No regrets. Bounced back. On my own two feet. Life is good. He expresses these sentiments so often that you start to believe him. He’s just as charming as he was in the film, more than 20 years ago.

I ask one last question: Can he still dunk? Maina lights up and offers to show me. The only problem: a basketball. We make plans to meet the following day on a court at a nearby primary school. I’ll find a ball; he’ll bring his game.

The Air Up There culminates in perfect ’90s feel-good movie fashion. Saleh, newly introduced as the starting center of St. Joseph’s University, walks off the court with Jimmy Dolan, who has been promoted to head coach thanks to his successful, if unorthodox, recruiting methods. They laugh, the music swells (“Higher and Higher”) and the final frame is a slow-motion high five. It’s so cheesy that it’s endearing. And it’s not unlike what I have in mind while I wait for Maina on the court.

It’s noon, and the sun is punishing. I have an hour before I need to make the trek back to the airport. Maina is late, leaving me plenty of time to play out the coming scene in my head. He’ll dunk, of course, and it will be a cathartic slam. Perhaps his trademark windmill from the film’s climactic scene. We’ll laugh, the music will swell, and Maina will realize that good times lie ahead.

After waiting a half hour, I head back toward the town center. My first stop is The Winds Club, where I first met Maina just two days earlier. No one has seen him. I decide to check another bar, Doc’s Pub, one that Maina pointed out the day before.

I step into the dark room. It could be anywhere, a place where people go to forget or be forgotten. There’s a man standing idly in front of the soft glow of a television. The bartender is concerned with something behind the bar, his back to me. Nobody acknowledges my presence. At the far end of the bar is the unmistakable 6' 9" shape of Charles Maina. He’s on a stool, head lowered, cradling a pint.

I ask where he’s been. He turns slowly and takes a few moments to recognize me. “I was there,” he says, his voice rising. He staggers to his feet and leans in close. “I was there,” he repeats, this time louder, more aggressive.

“I’m sorry if there was a misunderstanding,” I say. He takes a long breath; his wiry frame relaxes, and he puts his arm around me.

“Do you pray?” he asks.

“Sometimes,” I say.

“I try to, in the mornings,” he says, before losing his thought. We stand there, and I wait for him to continue, but he’s done talking. I tell him I have to leave, and he gives me a hug and wishes me well.

Outside, embarrassed by my own naiveté and guilty of the same latent paternalism as the film’s protagonist, I arrange a ride to the airport.

It’s hard not to get swept up in the current of a feel-good narrative. We crave stories of redemption and of success against incredible odds. But the true story of Charles Gitonga Maina isn’t a Hollywood-ready tale, just a complicated life. In the end, it diverges from art, and perhaps the two were never as connected as they seemed to be.

“Have I learned my lesson?” Maina wondered the day before. “I find it very hard to trust a human being. You give yourself, and they squeeze you out.”