Olympic Gold Medalists Believe California Bill Could Lead to Reduced Dominance at Games

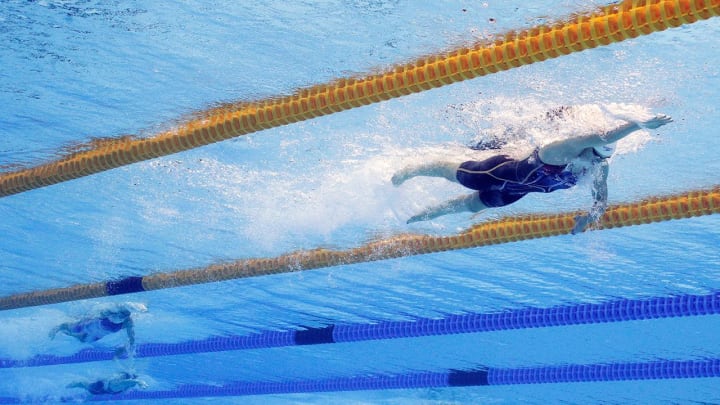

Four-time Olympic swimming medalist Anthony Ervin has a message for proponents of California State Assembly Bill 252, which he sees as a massive looming threat to broad-based collegiate athletics programs: “Without the opportunity to pursue both an education and sport, morale will wither and we’ll see some of our geopolitical rivals topping us in [Olympic] medal counts.”

Ervin is meeting with legislators in Washington, D.C., this week with two more United States Olympic swimming heroes, fellow gold medalists Summer Sanders and Maya DiRado, to discuss the bill that has passed the California Assembly and is headed to the state senate later this summer.

AB 252 would require the state’s 26 Division I schools to share revenue with athletes, particularly football and men’s basketball players whose sports generate the majority of that money. If the bill becomes law, the diverting of funding from Olympic sports—most of which do not create substantial revenue for their athletic departments —could lead to the widespread elimination of those varsity athletic teams. Most athletic departments distribute their combined sports revenue throughout the entire program.

And that, Ervin told Sports Illustrated on Monday, could do irreparable damage to the United States’ Olympic movement. A high percentage of the country’s Olympians are developed through the NCAA ranks; fewer opportunities to train and compete at the collegiate level could translate to weaker Olympic teams. While Americans might not rabidly follow those sports collegiately, they expect and enjoy dominance every four years internationally.

“I feel threatened,” Ervin says. “This bill is telling us—swimmers, Olympic sports athletes of all kinds—that our labor has no value at all, that we bring no value to the country. When we win medals and raise our flag—they have no value. Therefore, they’re going to strip away our efforts to get an education and pursue glory for our country. And I think that’s just sad.”

Ervin, who won three Olympic gold medals and one silver, swam collegiately at California. Sanders, who won four medals in the 1992 Summer Games, and DiRado, who won four in 2016, both swam at Stanford. They are scheduled to meet with a variety of lawmakers Tuesday—starting with Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, a Republican from California. Other Olympians will visit with state politicians in Sacramento later this summer.

“We want athletes to have all the support in the world,” Sanders says. “We love the fact that they’re able to create their own brand and make sure they have money coming in from NIL, but I just can’t comprehend how all those sports are going to exist under this financial model.

“The worry is that college athletics will become all about football and basketball. And all the other sports, if they’re lucky, will become club sports. Or they may go away. And where will our Olympians find themselves?”

In order to get the bill through the California Assembly, a number of amendments were made. Sports Illustrated reported some of those earlier this month: The creation of an athlete degree completion fund that would distribute new revenue equally between male and female athletes; a permission for colleges to use additional funds to ensure that non-revenue sports are maintained; a prohibition on eliminating sports teams and cutting individual scholarships.

While those might have appeased some lawmakers, the attempts to safeguard Olympic sports could be impractical in the real world.

“I don’t think there’s a very good understanding of the economics of sport,” Ervin says. “Not at all.”

The Olympians who are fighting for their sports emphasized they are not opposed to changing the current athlete compensation model. But they want politicians and the public to have an understanding of what the unintended consequences could be if football and basketball are assigned to their own financial silos.

“It’s just kind of a choice we’re staring in the face right now,” DiRado says. “As much as we agree that athletes should be compensated for what they bring in, there’s a lot of layers to this. There’s a lot of ways that benefits get accrued to schools and to the country as a whole.

“We’re making sure that Americans know, that as good as we feel every four years at the Olympics when our teams are absolutely dominating, it is not guaranteed and a lot of that is predicated on the collegiate Olympic-sport model. We understand the economic realities, and it’s more just making sure the consequences are clear of what a bill like this would mean.”

Pat Forde is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who covers college football and college basketball as well as the Olympics and horse racing. He cohosts the College Football Enquirer podcast and is a football analyst on the Big Ten Network. He previously worked for Yahoo Sports, ESPN and The (Louisville) Courier-Journal. Forde has won 28 Associated Press Sports Editors writing contest awards, has been published three times in the Best American Sports Writing book series, and was nominated for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize. A past president of the U.S. Basketball Writers Association and member of the Football Writers Association of America, he lives in Louisville with his wife. They have three children, all of whom were collegiate swimmers.

Follow ByPatForde