A Big-time Gamble

Oscar Bellfield was sitting on the wooden bleachers at the Westchester (Calif.) Recreation Center on a recent Sunday watching his younger sister play an exhibition basketball game when a teenage girl spotted him and hurried over. Her silver filigreed earrings rocked as she sat down one bench beneath him.

"So, what school are you looking at?" she asked.

"Different ones," he said.

"I heard you were up visiting [the University of] San Francisco?"

"Yeah."

"You gonna go there?"

Bellfield sighed softly. "I don't know."

"You don't know?"

"No."

Unhappy with the answer, the girl offered a half-hearted "See ya" and bolted down the gym toward someone else. Bellfield had engaged in two similar conversations in the last hour -- in each case sensing that his questioner was really asking, Why don't you know? -- and seemed close to his breaking point. "It's not easy to explain what I am doing," he said later.

In simple terms, what Bellfield is doing is gambling with his future. Last week, during the eight-day window for senior basketball players to sign letters of intent, Bellfield did not commit to a college. It was not because he lacked the talent or the grades (he has a 3.2 GPA and a qualifying SAT score). Nor did he lack for suitors; San Diego State, Santa Clara, San Francisco and Washington State all offered him a scholarship. Bellfield didn't sign because he has always dreamed of playing for a prominent Pac-10 program. There is a chance that between now and next summer he won't receive an offer from a program fitting that description, and also a chance that the four schools that currently want him will give their scholarships to someone else. But the 6' 2" Bellfield, a starter at Westchester High (26-7 last season), was once offered a scholarship by Washington and just last spring was being recruited by Oregon and Kansas. He believes he can get at least one of those schools interested again. "It's kind of like I am betting on myself," he says. "Do I really believe in my talent?"

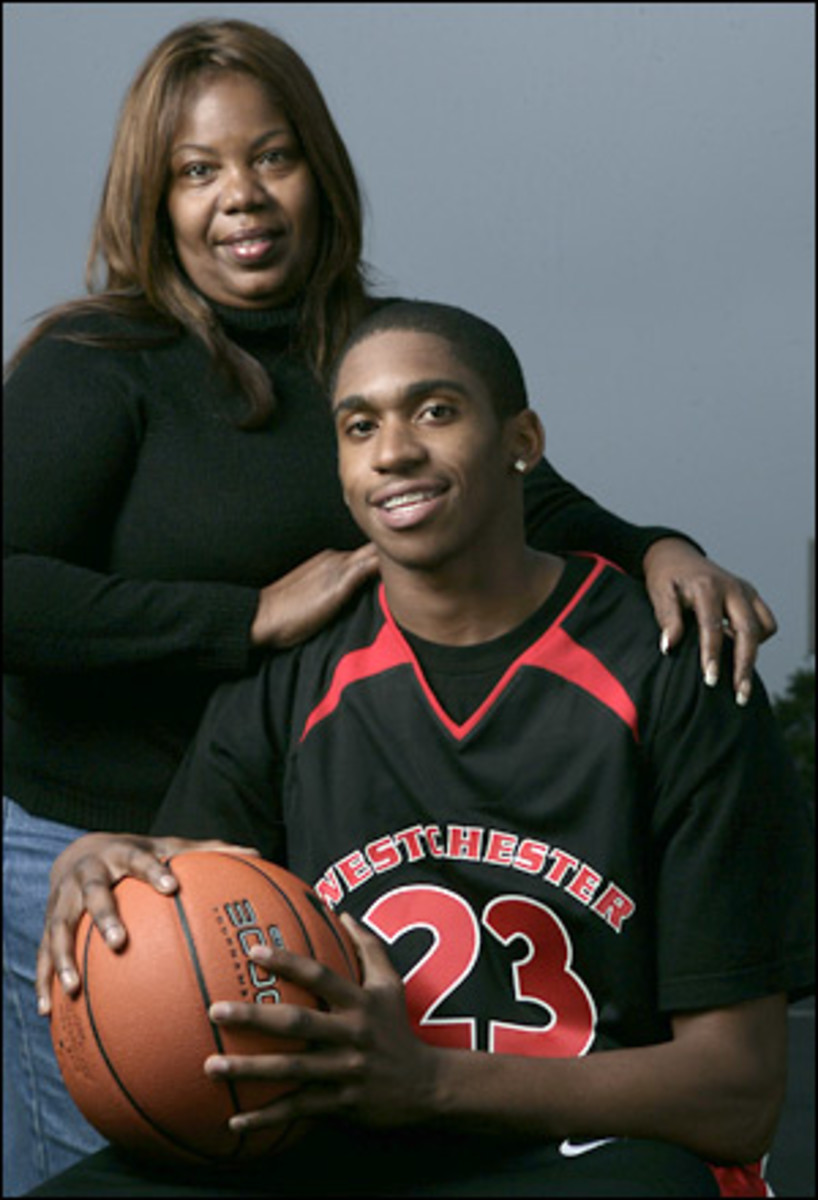

Bellfield is one of an untold number of good players across the U.S. who aren't ready to settle. The risks are real: With schools encouraging kids to verbally commit earlier and earlier, players who haven't signed with a school by November of their senior year seem like spoiled fruit; they are assumed to have flaws. "I know some people would say, 'You got a scholarship offer, you take it,' " says Lawanda Bellfield, Oscar's mother. "But Oscar, like a lot of boys, has a dream, and I wouldn't ever want him to give up on his dreams."

A confluence of factors put Bellfield in this position. Following his freshman year at Taft (Woodland Hills, Calif.), he received his first scholarship offer, from Washington. But Oscar and Lawanda felt (and rightfully so) that a player who gets an offer from a Pac-10 school before his sophomore year is like a stock on the rise. "We thought if he committed then, it might scare away other schools," Lawanda says.

After his sophomore year, Bellfield also received offers from Washington State and UNLV. He was getting letters and the occasional phone call from coaches at a dozen other major schools, despite not even being the most heralded guard on his high school team. He shared the backcourt with Larry Drew Jr., a top 50 guard. For his junior year, Bellfield transferred to Westchester and stepped out from under Drew's shadow. He was named second team Los Angeles all-city and led Westchester to the Southern California Division I regional final, averaging 14.3 points and 5.6 assists a game.

Last February the coaches at Washington pressed him harder to commit, as did the coaches at UNLV. He resisted, he says, because "I didn't want to commit just to commit. I didn't know where I wanted to go. Looking back, maybe I should have committed and then just kept my options open."

In the spring Bellfield played for EBO/2K Sports, a powerhouse AAU team based in Las Vegas that counts Washington Wizards guard DeShawn Stevenson and Utah Jazz forward Carlos Boozer among its alumni. During tournaments in Houston and Las Vegas, he starred. USC, Oregon, Utah, Boston College, Gonzaga and Kansas began calling regularly. They weren't offering scholarships but the message was clear: If Bellfield played well through the summer, the offers would pour in. "It seemed like everything was going to work out perfectly," says Lawanda, a nurse case manager.

Two months later, however, Bellfield pulled his right groin. He thought about skipping some tournaments, "but if you don't play, colleges will say you're not tough," Bellfield says. The injury was slow to heal, and he struggled the entire summer. The low point came in late July at the Adidas Super 64 in Las Vegas. "I had lost all my lateral quickness and couldn't jump," he says. "It hurt so much I could only play a minute or two at a time."

After that tournament, as if on cue, every school that was enamored of him in the spring suddenly lost interest. Moreover, Washington and UNLV, schools that had been pushing him to orally commit, stopped recruiting him.

Coaches rarely tell a player why they've lost interest (and it is against NCAA rules for them to comment on Bellfield for this story). Bellfield, who has since recovered from the groin pull, could only assume that they didn't know about his injury. "They had to be thinking that I was lazy, that I wasn't playing to my full potential," he said.

Bellfield watched as two other top point guard prospects from Southern California, his former teammate Drew and Brandon Jennings, signed with North Carolina and Arizona, respectively. "You read or hear about other kids committing or signing and you think, Wait, but that was my spot."

Darren Matsubara, Bellfield's AAU coach who is universally known as "Mats," has slicked-back Pat Riley hair and is fond of black sweatsuits. He is perpetually pulling a tin of Altoids out of his pockets. It is not a question of how many mints he goes through in a day but how many tins.

In September, Bellfield called Matsubara in a panic. Matsubara then called coaches at a few of the schools that had recruited Bellfield. "They didn't know he was injured," Matsubara says. "I don't know how they didn't see it, but they didn't."

Matsubara, 41, is known for not letting his players commit early. In a way, he is the Scott Boras of recruiting, always advising his players to let the market do its work. "There are 325 Division I basketball teams," Matsubara says. "That's a lot of options for a kid with talent." He knows that in the time between November of a player's senior year and the following summer, much can change. College players leave early for the NBA, transfer to another school, get kicked out, become academically ineligible or suffer a serious injury.

In discussions with Bellfield and his mother, Matsubara encouraged them to not accept offers from San Diego State, Santa Clara or USF, all of whom moved in after the bigger schools lost interest, or from Washington State. To support this course of action, Matsubara detailed two cases in which players had benefited from waiting.

• Last fall, going into his senior year, 6' 5" shooting guard Cory Higgins from Danville, Calif., had offers from only small programs on the West Coast. "There was some thinking that Cory wasn't an elite athlete, so we put him on my team for two [AAU] tournaments in the spring and gave him a platform to show his athleticism," Matsubara says. "We were throwing him lobs, all of that." After the second tournament, Higgins signed with Colorado.

• Also last year, Darshawn McClellan, a 6' 7" forward from Fresno, Calif., landed a scholarship from Vanderbilt after having offers from only Pacific, Cal-Poly and Fresno State in November. Vanderbilt was initially noncommittal, but that changed when Matsubara added McClellan to his roster for a tournament last spring. It was a not-so-subtle way of forcing the school into a decision. "College coaches know that a senior playing in the spring is in shape and going up against kids younger than him," Matsubara says. "That kid is going to look good, and history has shown you can use that as leverage. It may be the only time in recruiting that the kid has the upper hand."

One of Matsubara's favorite ploys could prove useful for Bellfield. He often hears that a player is thinking about transferring before the player's college coach knows it. Matsubara calls the coach and suggests to him a player like Bellfield. The coach might say, "I don't have a spot for him," but a few weeks later when his player transfers, he suddenly does. "And I am right there with a replacement," he says.

Bellfield likely needs a player to transfer out or to make an early defection to the NBA if he is to land at one of the two schools he most wants to attend -- Oregon and USC. Trojans coaches have told him as much, though he wonders if they are saying the same to other recruits. In the end he knows he can trust only his talent and Matsubara. "I believe I am a Pac-10 player," he says. Later, he adds, "And Mats can sell anything."

One consolation for Bellfield as he sweats out his senior season is that at least one top player and his mother learned from his travails. Justin Hawkins, a guard who played with Bellfield at Taft, orally committed to UNLV in August, a month before his junior year. At the time, several larger programs, including Tennessee, had begun to show interest, and he was tempted to wait and see which others called.

"We were influenced by what Oscar went through," says Carmen Hawkins, Justin's mother. "If something happens and we need to look around at other schools, we still can. But we know for sure that Justin has a school lined up that he likes."

Bellfield is hoping, and betting, that in a few months he will have the same.