Cherishing Baseball's Return

“Poets are like baseball pitchers. Both have their moments. The intervals are the tough things.” – Robert Frost

The images seem so antiquated they might well be viewed in a kinetoscope. Hugging. Massive amounts of hugging upon the final out of the World Series. It was only last year, which in COVID time is eons ago, or B.C. if you can remember what it was like to live without a conscious effort to survive.

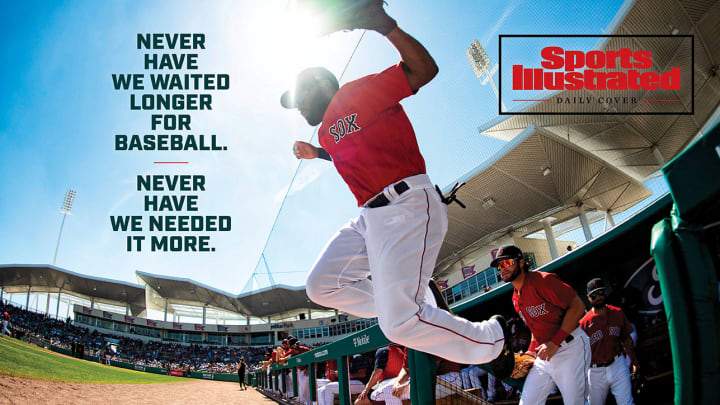

Two hundred sixty-six days will have passed between the Washington Nationals winning Game 7 and opening the 2020 season Thursday night. Never have we waited longer for baseball. Never have we needed it more.

The interval heaved with tumult. Owners and players bickered over money like some ugly public divorce. The behavior was all the more shameful because of the suffering and stress of COVID-19 and the outcry over racial injustice. The two sides never did come to an agreement. Commissioner Rob Manfred eventually leveraged a March agreement with the union to schedule a 60-game season.

“I think it’s important to re-establish our relationship with our fans,” Manfred told SI. “We’ve been gone since the end of October last year. People have been through a tremendously challenging period with respect to the virus and the economy. We’ve had our own issues with baseball.”

The return of baseball heals nothing. It is not that important. But its worth in these foreboding times actually is in its frivolity. The comfort of routine. The language of a box score. A ballgame on the car radio. The orderliness of runs, hits and errors–day after day.

The 101-page Operations Manual that details the health and safety protocols for this season is a dense document. But it is not without prose that passes for a mission statement on playing baseball through a pandemic:

“Adherence to the health and safety protocols described in this manual will increase our likelihood of being successful. We hope that resuming baseball will, in its own small way, return a sense of normalcy and aid in recovery.”

Reminders of the pandemic will be everywhere in the games. Masks and social distancing. Personal resin bags. No fans in the ballpark, no exchange of lineup cards, no throwing the ball around the horn after an out, no high fives, no fraternizing, no fetching a teammate’s hat and glove if he is on base when an inning ends, no spitting and no chewing tobacco.

But this strangest of seasons happens to be a moment of opportunity for the sport. The lazy pace of the game and the long season played better in more contemplative eras. Rumination died at the hands of our constant but passive consumption of entertainment.

Now the baseball season begins with urgency. Your team is in a pennant race at the start of August. September will see more games with playoff implications than any other final month of a baseball season, and no sport can match the episodic, enthralling nature of a pennant race. A loss to your rival is equivalent to 2.7 losses in a 162-game season.

Extra innings will begin with a runner at second base, creating not just a quicker end to games but a cascade of strategic decisions. All games have the DH.

“Look, I believe the 60-game season is going to be really exciting for our fans,” Manfred said. “Every single game is going to be meaningful. Given the extraordinary effort it takes this year, I think this champion is going to be a special champion.”

On paper, the Dodgers with MVPs Mookie Betts and Cody Bellinger and a boatload of hitters in a DH-deepened lineup are the best team in baseball. The Yankees, who scored the most runs last year, will be especially scary if they can keep Aaron Judge, Giancarlo Stanton and Gary Sánchez healthy for two months. The Nationals could break the longest streak without a repeat World Series champion (19 years) if they get to the postseason, because pitchers Max Scherzer and Stephen Strasburg, who carried them to wins in all 10 of their starts last postseason, have been rested. The Astros retain supreme talent and get a reprieve without fans in the stands to remind them of their sign-stealing scandal.

The Rays led the American League in ERA, the Twins hit the most home runs, and the Braves and A’s each won 97 games–all look to be elite again.

But when a 32-28 record might be good enough to get you into the postseason–that’s how the Rangers started last year–anything is possible. The Padres, with their power bullpen and a game-changer in Fernando Tatis Jr., the White Sox with their high-ceiling talent, the Reds with their deep pitching, and the Angels with Anthony Rendon hitting behind Mike Trout, are among the losing teams from last season most likely to be playoff-bound this year.

Just playing the season to completion is itself unpredictable. COVID always is in charge. Players are tested every other day. Since testing began three weeks ago, 80 players have tested positive out of a player pool of about 1,800.

“The one thing I will tell you is the players have been fantastic,” Manfred said. “You can test the tar out of people, but what prevents people from getting sick are the individuals who are actually involved in following the protocols. And the players have been fantastic.”

Twelve players have opted not to play this season.

“We expected there would be some opt-outs,” Manfred said. “The number is low because of two factors. The players in general realize we have taken extraordinary precautions to protect their health and their families. And they want to play baseball.”

The regular season will bring a new challenge: travel. Even with a regionally-based schedule, more movement could bring more risk.

“I think the next phase where we’re going to be doing more travel is concerning,” Manfred said. “I want to be clear about one thing: that our [health] experts really see the actual travel as safe the way we are doing it. It’s the moving where there is risk. You’re going from one risk environment to another.”

The season could be derailed by an outbreak among teams or by executive orders from local and state officials if the pandemic worsens. The Blue Jays will not play at home because Canada would not grant them an exemption to play in Toronto.

A positive test doesn’t mean an entire team will be quarantined. Only those teammates and staff members in “close contact” with the infected person will be isolated. Among the guidelines for determining “close contact” are spending at least 15 minutes within six feet of the infected person, sharing personal items, or being near coughing or spitting by the teammate. Each team has a pool of 60 players available for an active roster of 30 at the start and 26 for the final month.

Asked if he believed baseball can play uninterrupted through the World Series, Manfred said, “I’m cautiously optimistic. I think the protocols we worked out with the union were really good. I think the players and clubs have done a phenomenal job adhering to them.”

Born in 1874, Robert Frost was of a time when baseball was very much part of the soul of America. An amateur pitcher in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, Frost became friends with Edward Lewis, the former major league pitcher who became a professor and college president. Frost never lost his love for the game.

Frost was 82 years old when SI handed him an assignment: cover the 1956 All-Star Game in Washington. It might as well have been played on Mount Olympus. Four home runs were hit that day: by Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Ted Williams and Mickey Mantle, all with Frost playing the role of scribe.

When Frost filed his copy, the only poet to win four Pulitzer Prizes and the American institution who gave us, in haunting duplicate, the tag line “And miles to go before I sleep,” turned into a kid pitcher again at Rockingham Park in Salem, N.H. In other words, baseball transported him, or as he noted in his SI piece, “some baseball is the fate of us all.”

Wrote the bard as the cap to his story, “As I say, I never feel more at home in America than at a ballgame be it in park or sandlot. Beyond this I know not. And dare not.”

Sixty-four years later, the ballgame in Washington that starts the 2020 season features the Olympian matchup of Gerrit Cole against Scherzer, but only after Nationals fan and infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci throws the first pitch.

Baseball may be a long way from its status in America in 1956, but the circumstances that brought us to this unprecedented season could restore a bit of that eminence. The long interval is over. We are glad that baseball is here at all.

Tom Verducci is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered Major League Baseball since 1981. He also serves as an analyst for FOX Sports and the MLB Network; is a New York Times best-selling author; and cohosts The Book of Joe podcast with Joe Maddon. A five-time Emmy Award winner across three categories (studio analyst, reporter, short form writing) and nominated in a fourth (game analyst), he is a three-time National Sportswriter of the Year winner, two-time National Magazine Award finalist, and a Penn State Distinguished Alumnus Award recipient. Verducci is a member of the National Sports Media Hall of Fame, Baseball Writers Association of America (including past New York chapter chairman) and a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1993. He also is the only writer to be a game analyst for World Series telecasts. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, with whom he has two children.