Remembering the Fame of the Baseball Hall

Voting for the Baseball Hall of Fame can feel as joyful as the math portion of the SATs. Cherry-picking stats. Hair-splitting WAR figures to the right of the decimal point. Comparing players of different eras by the same metrics. Deciding on “right” and “wrong” answers entirely on a formula.

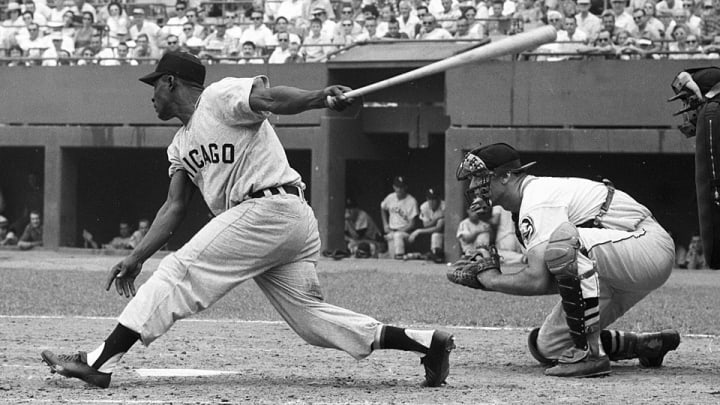

Today the Hall is a better place because two oversight committees went beyond numbers to remember the actual root of the place right there in its name: fame. The committees elected six players. Most importantly, four of them deserved enshrinement because of hybrid careers in which they continued to make significant contributions to the game after they finished playing: Gil Hodges, Jim Kaat, Minnie Miñoso and Buck O’Neil. Joining them as the newest inductees are Tony Oliva, the sweet-swinging Twins outfielder, and Bud Fowler, often acknowledged as the first Black professional ballplayer.

Statistics always will be the starting point for Hall of Fame consideration. Across a combined 45 ballots the baseball writers decided the playing stats of Hodges (best finish: 63.4%), Kaat (29.6%) and Miñoso (21.1%) were strong, but did not meet the 75% threshold for election. O’Neil was a .258 hitter in the Negro leagues with an OPS+ of 97.

But worthiness of the Baseball Hall of Fame does not end with a playing career. Other contributions to the game also matter. Character also matters. Fame also matters. O’Neil, for instance, was a Hall of Fame person and baseball lifer. His enshrinement is long overdue.

Hodges was the best first baseman over 12 postwar years and the leader of two of the most iconic teams ever: the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers and ’69 Mets. He hit the most home runs of any player who went on to win the World Series as manager. Hodges engineered the greatest upset in baseball history as manager of the ’69 Mets, deploying platoons and the innovation of a five-man rotation to protect his young arms.

“He was a gentleman,” says pitcher Jerry Koosman, one of many pitchers on that staff who went on to have long, healthy careers. “He commanded respect. He knew the game inside out. He was always three steps ahead of the other manager. I can’t tell you how elated I am.”

Hodges died from a heart attack in 1972 at age 47. His widow, Joan, is 95 years old. (She is also my aunt. Her mother and my grandmother were sisters who emigrated from Italy.) Joan watched her late husband fall excruciatingly short of the Hall for half a century.

Kaat won 283 games over 25 years, spent two years as Reds pitching coach, and has enjoyed a 36-year run as a broadcaster. Now 83, Kaat has worked in major league baseball over eight decades, starting in 1959.

Miñoso was a .299 hitter over 20 major league seasons, managed in Mexico, became a coach for the White Sox and in retirement was known as “Mr. White Sox.” He also had two brief appearances back in the big leagues with the Sox in 1976 and ’80, when he was in his 50s. He died in 2015.

O’Neil broke into the Negro American League in 1937, became player-manager for the Kansas City Monarchs, became the first Black coach in the AL or NL with the ’62 Cubs, became a respected and beloved scout, and was a driving force behind the Negro League Museum in Kansas City. He died in 2006 at age 94.

Don’t misunderstand. This is not an either/or exercise between stats and fame. The fame component does not mean the likes of Mark Fidrych, Joe Charboneau, Jimmie Reese or Don Zimmer are Hall of Famers. Numbers still matter. The committees’ voting results do mean that significant contributions atop a playing career worthy of the Hall of Fame ballot can be enough for enshrinement. There is room for hybrid candidates who fall short on playing career alone.

Dusty Baker is such a hybrid candidate. No manager has been elected to the Hall without winning a World Series, but Baker deserves a place in Cooperstown for his 19 years as a player and 24 years as a manager. Including the postseason, Baker had 2,023 hits as a player and has 2,027 wins as a manager.

Another Hall-worthy hybrid candidate is Bill Dinneen. He served 40 consecutive years in the majors: 12 as a pitcher and 28 as an umpire. Dinneen won three games in the first World Series (including the first two shutouts, and struck out Honus Wagner for the last out), won 20 games three straight years before hurting his arm, umpired eight World Series and the first All-Star Game, and was described by AL president Ban Johnson in 1922 as “one of the greatest pitchers the game ever produced and … one of the cleanest and most honorable men baseball ever fostered.”

Don Mattingly needs more work on his managerial résumé, but he is a former MVP who had 2,153 hits and has 820 wins over 11 seasons as manager.

Among the six newest electees, only Kaat and Oliva are living. It has taken too long for men such as Hodges, Miñoso and especially O’Neil to be officially welcomed into the Hall of Fame. Their contributions to the game already were legendary. Now that their unique places in the game’s history have been officially honored, they may make it easier for similar hybrid candidates to follow them into Cooperstown.

More MLB Coverage:

• Gil Hodges Belongs in the Hall of Fame

• Lingering Questions As MLB Lockout Puts Game on Hold

• Inside Baseball's Dangerous Game of Chicken

• Our No-Nonsense, Cut-the-Crap Guide to MLB's Labor War

• The Sure Thing: Why the Rays Extended Baseball's Next Phenom

Tom Verducci is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered Major League Baseball since 1981. He also serves as an analyst for FOX Sports and the MLB Network; is a New York Times best-selling author; and cohosts The Book of Joe podcast with Joe Maddon. A five-time Emmy Award winner across three categories (studio analyst, reporter, short form writing) and nominated in a fourth (game analyst), he is a three-time National Sportswriter of the Year winner, two-time National Magazine Award finalist, and a Penn State Distinguished Alumnus Award recipient. Verducci is a member of the National Sports Media Hall of Fame, Baseball Writers Association of America (including past New York chapter chairman) and a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1993. He also is the only writer to be a game analyst for World Series telecasts. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, with whom he has two children.