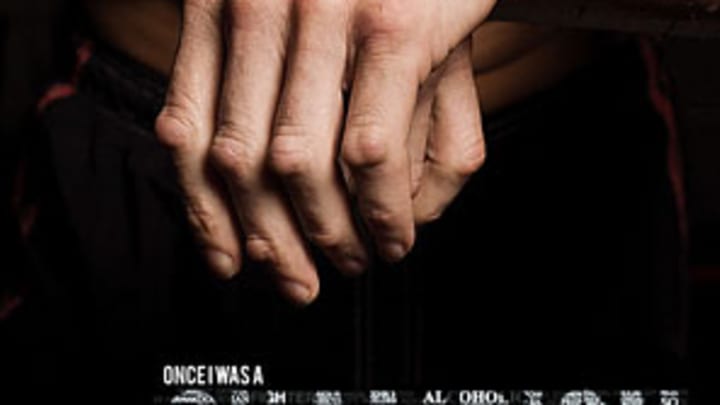

New film wrestles with fighter's mysterious final hours

New information surrounding the death of the film's tragic subject, Evan Tanner, had been brought to Roxburgh's attention by an SI.com reporter, shedding additional light on the former UFC champion's final hours in a desert about 143 miles east of San Diego.

Roxburgh had already screened the 93-minute film to some of the fighter's friends, family, and media two months ago. However, this new information was pivotal in any conclusions to be drawn as to why the troubled Tanner left his Oceanside, Calif., home on Sept. 3, 2008, hopped onto his motorcycle and rode into the 110-degree heat for a hiking trip he wouldn't return from.

According to the Imperial County Coroner's Office, Tanner died on Sept. 5 from heat exposure and environmental hyperthermia at the age of 37. On Sept. 8, Tanner's body was found two miles from his camp with the empty water bladder from his hiking hydration backpack lying next to him.

The film's previous cut culminated with the discovery that Tanner's blood alcohol level was .08, according to his postmortem toxicology report. It included an unidentified pathologist's statement that alleged alcohol use on the scene likely contributed to Tanner's death. That was a poignant note to end on, given Tanner struggled with alcoholism for years and the film's final moments centered on friends, team members and family debating if he'd finally found and maintained sobriety in the last months (and minutes) of his life.

Saturday's screening will now include a replacement citation provided by forensic pathologist Dr. Gregory J. Davis, who was contacted earlier this week by SI.com to discuss and review Tanner's case.

"All or part of that .08 level could be attributed to decomposition," said Davis, Professor of Pathology and Lab Medicine for the University of Kentucky, who's also one of the state's medical examiners. "Upon death, the body can produce alcohol when the gut's bacteria starts fermenting sugar."

The Imperial County Coroner's Office concurred with Davis and said of the many hyperthermia cases it investigates each year as illegal immigrants pass over the border into the United States, "all of the victims'" toxicology reports come back with blood alcohol levels present. In Tanner's case, the coroner's office said its investigation showed no evidence of alcohol at his campsite, near his body or on the path and the surrounding areas where he'd apparently hiked in search of a water hole that had long been dried out.

The addition has caused some last-minute shuffling, but Roxburgh, a 28-year-old graduate of the California State University-Long Beach film school, wants to get it right.

Since 2007, when he first asked Tanner via email if he'd be interested in documenting his road to sobriety as the fighter tried to stage a comeback in the sport, Roxburgh has had to overcome one obstacle after another to ensure Champion portrayed the complex fighter as accurately as possible.

At the time, Tanner, once a self-taught fighter who went on to win the UFC middleweight championship in 2005, was on a four-fight slide in his last five outings. Well-read, inquisitive and highly philosophical, the quiet and reserved fighter had begun sharing his meandering thoughts in lengthy posts on the Internet to connect with and inspire his fans. Roxburgh was among Tanner's receptive audience.

"He was drinking pretty heavily at the time and his life seemed to be in a downward spiral," said Roxburgh. "In retrospect, it was funny to think why he'd answer my email, let alone agree to do it."

Roxburgh didn't get the chance to question Tanner further. Shortly after their initial correspondence, Roxburgh returned to his native Greenock, Scotland, and spent the next year producing his first documentary film about his recently deceased great-uncle.

Returning to the States in 2008, one month after Tanner's death, Roxburgh felt a great opportunity had passed him by. "I guess part of me felt like I owed it to him," said Roxburgh. "I think he was the first person in the sport who was a main figure, a champion who tragically died, and there wasn't a big enough issue made about it."

Roxburgh's colleagues and peers, as well as his film mentor, advised him not to pursue the project. After all, Roxburgh had never even spoken with Tanner on the phone. Yet, Roxburgh, who trained in Brazilian jiu-jitsu and Muay Thai for eight years, said he'd been inspired by the writings and teachings of the UFC fighter he never got to meet in person.

"I'd written my first documentary into a narrative feature, and I just dropped it," said Roxburgh. "Everybody thought I was crazy, especially because they felt Evan's story was such a tragic one that there was no way I could make people enjoy the film."

Roxburgh met with Tanner's brother, Jeff, and younger half-sister Paige Craig in late 2008, but others in the fighter's family were hesitant to participate. Tanner hadn't kept up much contact with his mother or stepfather in six years, said Roxburgh. Brother Jeff eventually stopped speaking to Roxburgh altogether, but Craig agreed to help with the project five months later.

The first round of interviews was conducted by Craig and focused mostly on mutual friends the siblings had shared. As the scope of the film widened, Roxburgh took the helm, gathering interviews with Tanner's closest confidantes, teammates, trainers, business partners, romantic interests and fans. Roxburgh visited the house where Tanner was born, the high school where he became a standout wrestler and every gym the nomadic fighter had ever trained in.

"By the time I got to the desert [where Tanner died], it almost felt surreal," said Roxburgh. "I almost felt like Evan was a part of my family, as I became close to all the people he became close to."

In the next two years, Roxburgh collected 200 hours of video, from Tanner's early fights in his native Amarillo, Texas, to footage that a producer had shot of the fighter in Las Vegas for a pilot pitched to Spike TV. When he and fiancée Sophia Tavernakis, also one of the film's executive producers, ran out of money to fund the film, they got Tapout co-founder Dan Caldwell to watch the trailer. The clothing entrepreneur signed on as a second executive producer. Roxburgh conducted his final interview with UFC president Dana White.

Getting the proprietary promotion to license footage from Tanner's fights in the UFC was a lesson in research, persistence and sheer luck. Roxburgh edited in the clips he wanted, carefully following the fair use laws for film in case the UFC turned him down, then waited for their answer. Roxburgh caught a break on a visit to Thailand, where he randomly met a Spike TV producer who got him a direct pipeline to White and the permission he needed.

The final product is a sweeping narrative that successfully captures the many sides of one of MMA's most complicated figures. It has a heartbreaking honesty not seen since 2002's The Smashing Machine: The Life and Times of Mark Kerr.

In a letter to movie director and friend John Herzfeld, who at one time penned a script surrounding the UFC and the sport, Tanner the poet makes no attempt to hide his vulnerability and loneliness while describing his stripped apartment after his fiancée has left him.

Coaches and teammates describe Tanner the pacifist, a torn fighter truly pained to have to step into the cage and hurt another man in the name of victory. Former Team Quest teammate Ryan Schultz recalls Tanner the belligerent drunk, who hauled off and punched him one night at a bar when Schultz tried to get him to leave.

Fans honor Tanner the activist by proudly showing off their tattoos with the fighter's pay-it-forward mantra to "Believe in the power of one."

"People had such differing opinions of who they thought he was," said Roxburgh. "Some people knew him when he was sober and thought he was such a go-getter. Others knew him when he was drinking and described him as a depressed loner. Others said Evan was the most fun when he was drunk. He wore different faces around different people."

Champion also holds historical significance for the embryonic sport still shy of its 18th birthday in the United States. Benji Radach, a fighter and Tanner cornerman, provides one of the most memorable scenes, as his camcorder tracks the fighter entering a half-full arena, and captures the moment Tanner's team rushes him following his championship turn against Dave Terrell at UFC 53 in 2005.

Like the dichotomy seen in the self-destructive Tanner's crusade to change the world though he's unable to save himself, Roxburgh believes the documentary's dual messages will encourage those that need support to seek it out, and for those that have the capability to offer a lifeline, to do so.

"I think that was Evan's biggest flaw, that he never sought out a support system for a long enough period of time," Roxburgh said. "Still, he showed that you have the power to influence people, regardless of any situation that you're in. Even through death, Evan's achieving what he wanted to: effecting people on a one-on-one basis and making a difference."