Playing Through The Pain

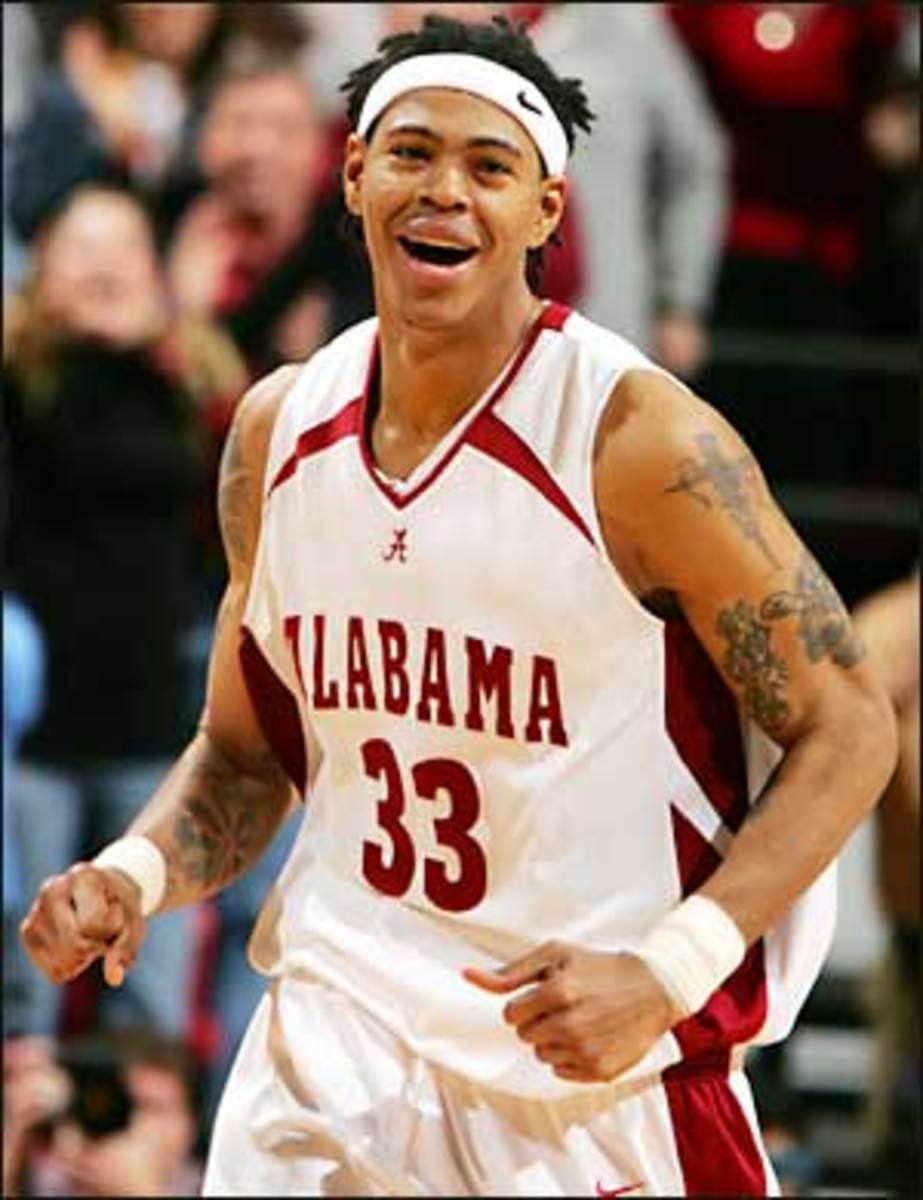

At first glance, the MySpace page of Alabama forward Jermareo Davidson looks a lot like that of any other college student. There are loads of photographs, a song playing in the background and goofy, half-intelligible messages from friends. But take a closer look. Read the preamble across the top of Davidson's page: "November has been a rough month for me...." Listen to the song, Ky-Mani Marley's mournful I Pray. And watch the continuously looping photo montages, digital elegies to two fallen pillors of Davidson's life.

One shows pictures of a willowy young woman framed by electronic roses, floating hearts and a simple farewell: Live in the sky ... Nikki, love u 4ever, RIP. Just below that, another series of photos presents a young man with piercing eyes, a goatee and dreadlocks beneath another postscript: RIP BIG BRA.

On Nov. 7, just three nights before the start of a senior season that Davidson, one of the nation's leading big men, hoped would lead him to the Final Four and the NBA, his brother, Dewayne Watkins, was shot in the neck by an unknown assailant. Four days later Davidson and his girlfriend, Nikki Murphy, visited Watkins at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. That night, as they returned to Tuscaloosa, Nikki, who was driving Davidson's SUV, lost control as she swerved to avoid another car on Interstate 20. The vehicle flipped several times before landing on its roof.

Davidson, who says he was wearing his seatbelt, walked away unharmed, but Murphy was thrown from the vehicle and died several hours later -- in the same hospital where Watkins would die on Dec. 20. Davidson is still coming to terms with the two tragedies. "I have my tough moments, like right before we go on the court, but I'm able to move it to the side until later," he says. "The times I break down are when I'm alone, just sitting at home in front of the computer."

Sitting and staring at his MySpace page.

Madonna Davidson can't help it. She's a loud, proud mom, and this is a big game. So she cheers when her son goes up strong against LSU's Glen (Big Baby) Davis, cheers again when Jermareo lofts an old-school skyhook, and cheers loudest when then No. 14 Alabama seals a 71-61 win. There's nothing unusual about her fervor, except for where it's being displayed. She's not sitting in the parents' section; she's standing in the second row of the student section, among the craziest of the Crimson Tide crazies. "Jermareo's heart is hurting, but I'm so proud of him," Madonna says. "I tell him, 'You've got to use Nikki and Dewayne's love for basketball as a driver because that is what they would want you to do. You've got to keep striving. You've got a story to tell, a story to uplift somebody.'"

Some of Jermareo's passion for the game came from Dewayne, who was five years his senior and a point guard in high school. Growing up in the Capitol View neighborhood of Atlanta, the boys would play ball nonstop on the goal Madonna had set up in the backyard. "I have thousands of memories [of my brother]," says Davidson, smiling. "The last Thanksgiving that I went home, he cooked for me and [teammate] Alonzo Gee." Turkey, collard greens, mac and cheese; it was a perfect holiday spread from the guy who called his younger brother Jay-O. "Whenever he came into the gym, I knew he was there," says Davidson. "That always got me hyped."

On Nov. 7 Davidson got a call from a family friend: Dewayne had been shot in an Atlanta suburb. The first person Davidson contacted was Nikki, whom he had met in a health class when they were freshmen. A student athletic trainer for the women's team, Nikki hoped to work in the NBA or WNBA one day. She more than anyone encouraged Davidson to be serious about school. "She said we couldn't have a future unless I graduated," he says. They kept their relationship secret because her job prohibited her from dating athletes, so they called each other cousins. ("What's up, cuz?" he'd say in front of her friends. "You calling Grandma tonight?") Only recently had they started using the terms boyfriend and girlfriend, and every Thursday they would go bowling together.

"My brother's been shot," he told her that night. "Can you ride with me to Atlanta?"

"I'm already packing," she replied.

They visited Watkins, who was paralyzed and on a ventilator, and returned to Tuscaloosa for Davidson's season opener three days later. After the Tide's 96-65 win over Jackson State, they drove back to Atlanta and saw Watkins again the next morning. Davidson says he won't forget the haunting details of their drive home that night. The song playing on the stereo (Beyoncé's Irreplaceable). Nikki's scream ("Baby!") as she swerved off the expressway, losing control of Davidson's blue 1998 Ford Explorer. And, not least, his pleas as he crouched down next to Nikki on the asphalt and waited for an ambulance: I love you ... keep breathing ... I love you ... keep breathing.

Davidson, riding in the ambulance with Nikki, returned to Grady Memorial. As Nikki underwent emergency surgery, Davidson waited to have his back examined. "They gave me some medicine, I think to put me asleep," he says. "When they woke me, they told me that Nikki had passed." Brandy Nicole Murphy was 21 years old.

When Davidson rejoined the Crimson Tide after missing just one game following the car accident and Nikki's funeral, his teammates were amazed by his courage. "I don't know if I'd be strong enough even to think about basketball," says point guard Ronald Steele. "I don't know how he does it." Not that the process has been an easy one. "He had a few days when you could tell he'd been crying all day," says coach Mark Gottfried. While Gottfried thinks Davidson's best games this season are still ahead of him, the coach notes, "He's played great considering the circumstances," averaging 14.3 points and a team-best 9.0 rebounds a game.

The way Davidson sees it, basketball is more valuable therapy than just about anything else he's tried. At the suggestion of his coaches, his mother and the team chaplain, Kelvin Croom, he met with two grief counselors, neither of whom he has visited since. "It just made me sad all over again," he says. Some of his inspiring conversations, he says, have been with Nikki's mother, Edwina Murphy. "She knew how serious we were," Davidson says.

Last month Davidson was able to withdraw from school before exams and then regain his eligibility a week later thanks to an NCAA rule that grants an exemption for an athlete whose ability to attend college is hurt by an incapacitating injury or illness to himself or a member of his immediate family. "I'm still struggling," Davidson says, "but I've been able to live through basketball because both Nikki and Dewayne supported that part of my life." Davidson honors his girlfriend and his brother during games, forming a "B" sign with his hands for Brandy and pounding his fist against his chest, where he has a tattoo of Dewayne's face, before shooting free throws. (Another tattoo, on his right forearm, depicts Nikki as an angel in flight.)

How has Davidson found the strength to play basketball? How has he stood up to the pain? Perhaps the answer lies in the scene that took place on Dec. 28, during his brother's funeral at the Capitol View United Methodist Church in Atlanta. The night before, he had stunned his mother by telling her he wanted to be baptized in the church that he and Dewayne attended as children. So after giving his eulogy, Pastor Otis Pickett asked the congregation if anyone wanted to be saved. Davidson came forward. "It really was a powerful moment for every one of us who was there to witness it," says Croom, the brother of Mississippi State football coach Sylvester Croom.

And so, in a church that was filled to capacity, a grieving giant kneeled on a pillow, asked for forgiveness and gave his life to the Lord. Afterward, nobody could tell whether it was holy water or tears running down Jermareo Davidson's face.

Issue date: January 29, 2007