Turnaround Wizard

I picked him up at the airport in Bangor, Maine, and I asked him, 'How many bags have you got?' He said he had four. I said, 'Good. That will take you only two trips to get it in the van.' And I walked off and left him. Let him make two trips carrying the bags by himself."

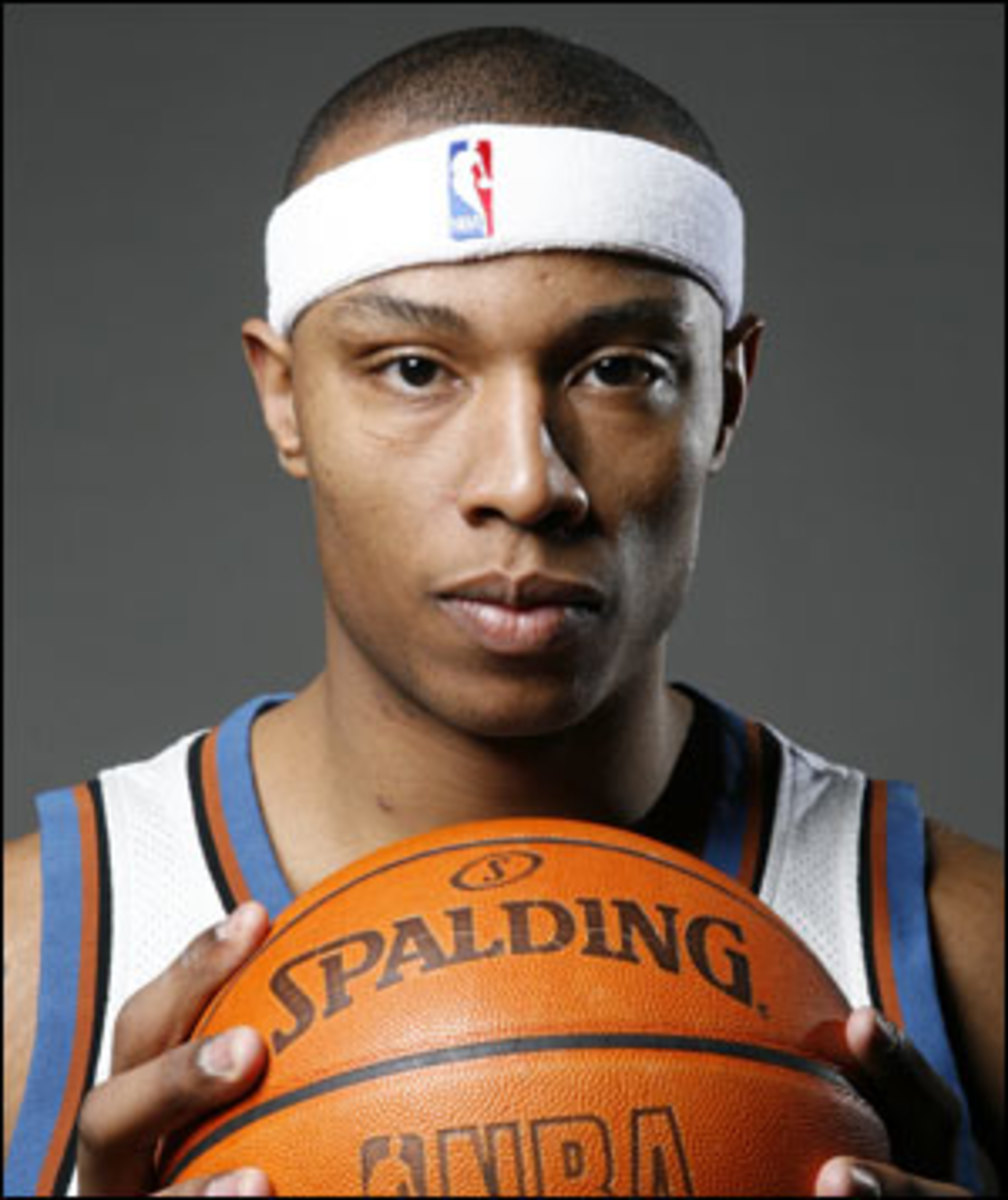

The narrator was Max Good, the former coach of Maine Central Institute, a prep school in the middle of who knows where. He and his wife, Phyllis, were sitting in end zone seats 16 rows from the court on which the Washington Wizards were playing the Celtics on a recent night in Boston. He was explaining how Wizards forward Caron Butler had begun his transformation from an adolescent criminal into an NBA All-Star.

"He'd flown in from Racine [Wis.] to Chicago, Chicago to Boston, Boston to Bangor, so I knew he was hungry," Good was saying. "After I picked him up at the airport I drove to a McDonald's, and I had an Airedale terrier that I took everywhere with me. We went to the McDonald's and I fed my dog, and I got something, and I didn't even feed Caron. My dog was eating and he wasn't, and I knew he was thinking, Damn."

As Good spoke, Butler was playing a typically sensational game. He was routinely slashing to the basket or shouldering off Celtics defenders to clear space for his smooth jumper, and when he went up for rebounds, he would snatch the ball above the crowd, his upper body jerking and thrashing like a swordfish against a fisherman's line. With an explosive first step and the attitude of a running back who seeks contact, he was, at 6'7" and 228 pounds, the most intimidating player on the floor. "Caron, Carmelo Anthony, Paul Pierce -- they all have great direct lines to the basket," says San Antonio Spurs small forward Bruce Bowen, who regularly defends the best wing players in the NBA. "Caron doesn't pump-fake and dribble around the contact. He pump-fakes and goes straight to the basket."

Yet in between plays on that night in Boston, the All-Star would look up into the crowd at his old coach. Rather than being distracted by his tortured past, Butler was drawing strength from it.

"And so we're driving down the highway, and it's about 35 minutes from the airport, it's a light night and you can see the silhouette of the trees because it's nothing but pine trees between Bangor and Pittsfield [where MCI is located]," Good was saying. "And Caron said, 'Coach, it doesn't seem like there's much to do here.' So I jerked the van over, and I said -- you've got to excuse my language here -- I said, 'Hey, [expletive], do you want to go back to Racine, where you had so much to do and got absolutely nothing done?' And he said, 'No, no, no, no, Coach, I'm not saying that.' I said, 'Will you learn from me and learn to shut the [expletive] up and start listening instead of talking?' And he didn't say another word."

Memories of those teen years have helped propel Butler to his finest season. Career-best averages of 20.5 points, 7.8 rebounds, 3.8 assists and 2.12 steals earned him a berth in his first All-Star Game, in Las Vegas on Sunday, and a place among the best players in the world, but his larger mission to maintain his drive and self-discipline prevents him from feeling too comfortable in the company of stars. He holds himself erect and proud, like a military officer who never can loosen up at the neighborhood cocktail party.

Butler has emerged as the most reliable player on the East's most surprising team -- the Wizards had the best record in the conference before a recent skid dropped them to 29-21 -- and at 26 he has been guaranteed enough money to secure himself and his extended family for life. But he is always bracing for the possibility that his success could be taken from him at any moment. "So many people are saying, 'He proved himself, he's doing great,'" Butler says. "But I still think, in the back of my mind, I still think that I'm...." If he could bear to finish the sentence, it would go something like this: He still sees himself as the uncertain and famished young man he was on that 35-minute ride from Bangor to Pittsfield.

Which is why he remains so surprised and grateful by the reception that greeted his arrival in Washington two summers ago, after the Wizards acquired him from the Los Angeles Lakers in a deal for former No. 1 overall pick Kwame Brown. Before Butler played a game for his new team, Washington offered him a five-year, $50 million extension. He signed the contract on Oct. 31, 2005 -- the 10th anniversary of his sentencing for bringing a gun and a small packet of cocaine to Park High in Racine as a 14-year-old freshman. "I used to think about that every time Halloween came up," says Butler, who served three months in county lockdown and another 11 months in a maximum-security juvenile facility. "Now on Halloween, I think, This is the day I got $50 million. It's amazing how things can change."

Wizards general manager Ernie Grunfeld had begun to follow Butler's career in 1999, when Grunfeld became G.M. of the Milwaukee Bucks. It is a renowned cautionary tale throughout the NBA that Butler was arrested 15 times by the time he was 15 years old, for offenses ranging from weapons to drug possession, but what was less understood -- and more intriguing to Grunfeld -- was the disciplined path he had followed since he started over at Maine Central. Not even Grunfeld foresaw the exponential growth that has made Butler an early favorite for the NBA's Most Improved Player award this season. "I'm not going to sit here and say that we saw it coming, because we didn't," says Wizards coach Eddie Jordan of Butler, who had career averages of 14.6 points and 5.5 rebounds entering this season. "You would have thought maybe he would be a little bit better than average, but the drive he has is something you don't [usually] see in people."

Max Good did see it all coming. "I didn't want the NBA in his mind," says Good, "but it was in mine." He refers to Butler as one of the finest people he has ever coached, a "no-maintenance" player who averaged 26.2 points and 13.3 rebounds in his second year at MCI and was the top prep school player in the country. But Good didn't dare share his feelings with Butler, because his goal was to drive him as far as he could go after his escape from the violent world he knew in Racine. Butler would become one of nine NBA players to pass through Good's gym during his 10 years in Pittsfield. "I used to hold up my fist and tell them, 'Guys, you know what this is?'" Good says. "I'd say, 'This is your testicles; I got your testicles right in my hand. And I can end it for you if you decide not to do what's exactly right, because I control your whole destiny.'"

The stereotype of the entitled and self-indulgent NBA star does not apply to Butler. From the day he met Good he was trained to believe that every day could be his last on the basketball court, that his criminal record might cost him everything if he committed but one more mistake. His instinct for self-preservation seemed to draw him to disciplined, highly structured coaches like Good; Jim Calhoun at UConn, where Butler played for two years; the Miami Heat's Pat Riley, who took Butler with the No. 10 pick in the 2002 draft; and the Lakers' Phil Jackson, who picked up Butler for the 2004-05 season as part of the Shaquille O'Neal trade. After seven years of taking orders and constraining himself for the sake of his teams, Butler was confounded and overwhelmed when the Wizards acquired him to become a star. They needed someone to fill the slot vacated by Larry Hughes and create a new Big Three alongside All-Stars Gilbert Arenas and Antawn Jamison. It took Butler all of the '05-06 season to come to grips with what they were asking of him.

He entered the off-season with a new sense of purpose. "I didn't want to shortchange myself," he says. "I would see so many of these great things my peers were doing, and I'd say, Why not me? I don't think there's a player in the league who has been through the things I've been through, so I knew I was strong enough to handle any situation. So I said, I've just got to get my body prepared, and that's what I did."

Last summer, training in Washington, D.C., he ran hills in the morning, worked out twice a day and dropped 15 pounds thanks to the healthy meals prepared by his new personal chef. The early returns have emboldened him to be a leader as well as a scorer, per the wishes of Jordan, who has told Butler that he will become a co-captain for the second half of the season. According to teammate Calvin Booth, Butler is the one Wizard who will speak up when Arenas is goofing around before a game.

"I say things like, 'Are we going to work today, or are we going to continue to talk?'" says Butler in his deepest baritone voice. "Because sometimes there's too much lollygagging going on. I'm like, 'Hey, do y'all know we got the Pistons out there? Are we going to work today?' Everybody gets real quiet, like, Oh, here he goes. But I get the respect I deserve."

Butler dreams of extending his influence beyond NBA arenas to the broken neighborhoods of Racine, where he returns each summer to visit his mother, Mattie Paden, and his brother, Melvin Claybrook, a 6'3" senior guard at Park High. His charitable foundation supports an annual coat drive in Racine, and Butler visits local schools and meets with students and friends to try to set an example. "When we go to Racine he always tells me, 'Remember this person's face,'" says his wife, Andrea, who met Caron when they were freshmen at UConn. "A year or two later he'll say, 'Remember that person?' And he'll tell me that he's gone or he's been shot or he's in jail."

"It's never failed," says Butler of his premonitions. Of his six closest childhood friends, four are dead. Last May it was a 25-year-old named Robert Nelom. "I told my wife, 'I just don't think he's going to get off the streets.' And six months later he's dead. He got shot in the head -- got shot twice, actually, in a club in the bathroom. I had to go back and bury him."

On Sunday in Las Vegas, Butler missed his first six shots and didn't score until there was 4:07 left in the East's 153-132 loss. "He whispered to me, 'I was a little nervous out there,'" said Jordan, who as the East head coach played Butler for 16 minutes off the bench. "I said, 'Heck, Caron, I was nervous all day and got more nervous as the game time approached.' It's all about the experience. He's going to have a comfort level when we get back, and he's going to be riding the wave."

Indeed, Butler sees Sunday as the first day of his newly elite career. "I want to be a perennial All-Star," he says. "I'm very grateful for this honor, but I think I can get much better. I can take it to another level."

A month earlier, after scoring 23 points, grabbing 11 rebounds and handing out seven assists in the win over the Celtics, Butler came out of the locker room at TD Banknorth Garden to find Good, who left MCI in 2000 and now coaches Division II Bryant University in Smithfield, R.I., waiting near the court.

The two exchanged memories for a few minutes before Butler's teammates began to file past. The Wizards' bus was preparing to leave. Good leaned in close and wrapped his arms tightly around his player.

"I love you," he told Butler, and slapped him on the back. "You are an All-Star, I'll say that."

But that was not the kind of thing Butler wanted to hear. He gently pushed the old coach to arm's length, held him by both shoulders and looked him in the eyes. "Hey," he said softly, "be sure to call me sometime and cuss me out again."