The Pride Of Iowa

From an altitude, which is how most people see it, Iowa in winter is a dreary quilt-work of corn stubble. But a gradual descent reveals a friendlier geography. Roads finally form an intersection. A white church steeple or a water tower announces a concentration of people. A town materializes. Iowa has its cities, of course, but it's mostly a stitching of small towns -- that much is clear from overhead -- none of them any bigger than they need to be to service the land around it.

And in his office Dan Gable is saying he could drive to any one of these towns -- no matter how small, featureless or remote -- and find me a wrestling story. "That's just the way it is," he says. "It's Iowa."

In Humboldt (pop. 4,452) they still talk about Frank Gotch, the sport's Babe Ruth. He was the professional heavyweight champion from 1906 to '13 and famous enough for it that he was invited to the White House to meet Teddy Roosevelt. In Sheldon (pop. 4,912, A REALLY NICE PLACE!), they still talk of the Brands twins -- Tom and Terry -- a couple of hyper handfuls who became Olympic medalists, Tom winning a gold in '96, Terry a bronze in 2000. Cresco (pop. 3,905, IOWA'S YEAR 'ROUND PLAYGROUND!) somehow produced five admirals and a Nobel Peace Prize winner as well as two Olympians, a couple of college coaches and scores of individual champions. The Nobel laureate, Norman Borlaug, wasn't one of the champs; he finished second at the state tournament, in '32.

In fact, the only school to have piled up more hardware than little Cresco in the 87 years of the state tournament -- a fever dream of small-town America -- is Gable's alma mater, West Waterloo High. Waterloo is no town (pop. 68,747, BIG CITY EXCITEMENT ... HOMETOWN HOSPITALITY), but it's no Des Moines, either. Yet it supports a wrestling museum with Gable's name on it, several vibrant high school programs and a tradition that belies its size. Bob Siddens, who won 11 titles and coached more than 50 individual champions at West Waterloo, walks around town, all dapper and crisp at the age of 81, recalling all the "lads and lassies" he coached, and is accorded John Wooden respect. Gable, 58, was a three-time champ under Siddens before earning three titles at Iowa State, winning Olympic gold at 149.5 pounds in 1972 and then coaching Iowa to 15 championships in 21 years. (Wooden, by the way, won only 10 in 27 seasons at UCLA.) He is treated more along the lines of a god.

For decades the state's top high school wrestlers followed the roads out of town to Iowa City or Ames. Iowa and Iowa State combined for 26 NCAA championships and produced 60 wrestlers, who won 91 titles from 1968-69 to 1999-2000. But then both programs fell into relative doldrums. To remedy that, they hired coaches who embody the sport's greatest glory, and each is rebounding fiercely. In its first season under Cael Sanderson -- perhaps the most accomplished U.S. wrestler ever, having won Olympic gold in 2004 after going undefeated in four seasons at Ames -- Iowa State is ranked No. 2 going into the NCAA championships, which start on March 15 in Auburn Hills, Mich. Tom Brands left Virginia Tech last April to take over at Iowa. He has lifted the Hawkeyes to No. 10, aided by an assistant with a few credentials himself, Gable.

Wrestling is characterized by nothing so much as work ethic, which is something worth celebrating and remembering in a place that requires so much of it. Iowans like their football and basketball, too, but they love their wrestling. And this passion has transferred directly into an extended excellence that neither Indiana in basketball nor Texas in football can claim. The lore is pure Americana, reminding us of a permanence of achievement and small-potatoes glory that doesn't seem possible outside places like Iowa. Would Bob Steenlage persevere in memory if he'd been California's first four-time high school champion? In Britt (pop. 2,052; FOUNDED BY RAIL, SUSTAINED BY PLOW), he remains famous, hauled out for newspaper reminiscences 45 years later.

Even Northern Iowa, in Cedar Falls, and Cornell College, in Mount Vernon, have won NCAA titles, giving the 30th most populous state a total of 30. Oklahoma is a powerhouse too -- between them, Oklahoma State and Oklahoma have 41 -- but other programs advance tentatively, mindful of the mystique. Minnesota coach J Robinson, who assisted Gable for 12 seasons (and who poaches an Iowa four-time state champ, like 133-pound Mack Reiter, when he can) has the No. 1 team, having crushed Iowa 29-13 in a meet last month. But he does not anticipate a reworking of wrestling mythology anytime soon.

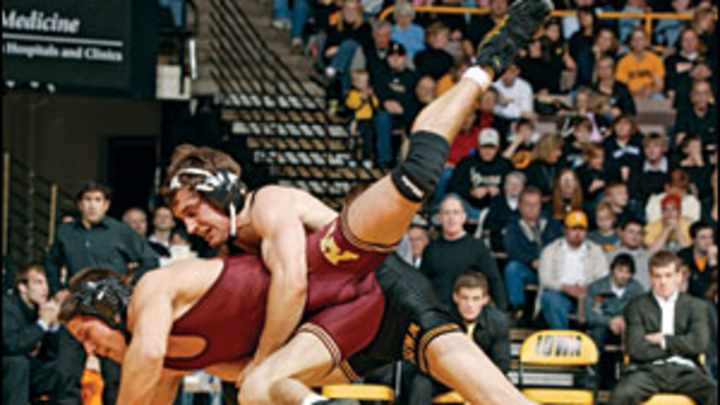

"At Minnesota," he says, "we've got a minor sport. In Iowa, it's still a major sport. There's a different mind-set, a different attitude. Wrestling is important. I mean, [the Hawkeyes] have their own beat writer." When the Golden Gophers came to Iowa City, 8,274 fans showed up. Iowa, which has won "only" three championships since Gable left in 1997 -- his successor Jim Zalesky was replaced after finishing fourth in the NCAAs last year -- still leads the country in attendance, with 6,740 fans per meet.

Iowa State has a formidable tradition as well, and it's rebuilding, too, perhaps at a faster clip than its rival. Under Sanderson, the Cyclones are in the hunt for their first championship in 20 years. For all his success, though, the 27-year-old Sanderson remains something of an outsider, having grown up in Heber City, Utah. But he understands Iowa wrestling. "When I came to Iowa State as a freshman," he says, "and, remember, I'd been a four-time champion in Utah, somebody asked me if I thought I could have won even one in Iowa. That's the attitude."

To maintain such tradition, such attitude, in the face of increasing distractions and competition from other sports is nothing less than a marvel. There is no reason that other, more populous states, shouldn't surpass Iowa. Brands says the top high school programs right now are in New Jersey and Ohio. His best prospect, who won't be eligible until next season, is from Michigan. But he knows, all the same, that the key to success is to recruit those four-timers, the small-town legends, the hard-nosed and aggressive ones, and make them competitive at the college level. "These fans deserve that," he says. "They expect that."

To help stoke the locals' fires, Brands coaxed Gable out of his fund-raising job in the Hawkeyes' athletic department and onto his staff. There is no equivalent to this move, not in any sport, at any level, unless the Green Bay Packers somehow coaxed Vince Lombardi out of eternity to call plays from the press box. Gable's role is somewhat mysterious, in that he refuses to offer his former pupil any unsolicited advice. But his impatience with losing might provide the program with just enough impetus to regain its stature.

The day after the Minnesota loss, for example, Gable was radiating pure disgust. "Three takedowns!" he said, referring to Iowa's paltry output. "I can get three takedowns before I get out of bed. And by that, of course, I mean my wife." Like Brands, he believes Iowa wrestling is a civic trust: "People here love this sport, and they've seen some great wrestling. We had a style that people are craving, a dominant style, pushing, shoving, snapping, wrestling to the edge, standing toe-to-toe. They've seen enough of that for 50 years to know the difference. They've seen meets with 10 competitive weight classes, not a 'cigarette break' in there. They are highly expectant. We had a team -- Brands was part of it -- when we had 11 All-Americas in 10 weight classes." He returns as asked, caretaker of this trust.

Gable is an odd duck, his intensity and fear of losing probably no longer as contagious as they once were. Still, you cannot be around him for long and be unaffected. As an aside, he brought up that miserable blight on his career -- a loss in his final NCAA match, when the particulars of his unbeaten career were being etched in trophies. He was distracted, he admits, and the defeat proved properly transforming. "I wouldn't have been the man I am, the coach, or the husband and father, without that loss," he says.

But he still mourns it. "I remember the depression afterward," Gable recalls. "I went back to school, but I physically couldn't talk to my parents when they called." He reenacted the scene, reaching to answer an imaginary phone call. "I'm choking up right now, a little bit." His mother mistook his silence for -- who knows what? -- and drove to his campus dorm, knocked on his door and slapped him. He laughs at the memory, a little. It was 35 years ago, after all.

It may be that fear of losing is not something you coach, anyway, but something that's instilled in all those small gyms in all those small towns where farm boys escape a comparative drudgery for one that promises at least a little fame, however local. Bill Smith, the 1952 Olympic gold medalist, recalls that he and his Council Bluffs teammates hated to wrestle those farm boys at state. "They were just stronger than us," he says. "They had these powerful grips. Milking cows, we always figured."

Brands, whose intensity is almost comic, tries to explain what it's like to be from a small town and do something memorable. "My first state tournament," he says, "I was one and out. But I remember the drive home on the bus, sitting next to our heavyweight, who won a championship, and he was on top of the world. He's a garbage man back in Sheldon, haven't seen him for years. But he's a champion forever."

It's almost impossible, in fact, to explain the hold the state tournament has on Iowa each February. There were 23,000 requests for 13,700 tickets this year. Driving home afterward from Des Moines to Iowa City every year, Gable admits that he falls into a depression. "Not a long one, but a depression." When I ask him why, he shoots me a look. "Because it's over."

Some of these kids will go on to wrestle in college, and some of them will then return to their little towns and nurture their own three- and four-timers. In Iowa City two former Hawkeyes who were NCAA champions coach rival programs, Brad Smith at City High and Mark Reiland at West High. It's not unheard of.

In Iowa wrestlers wear their letter jackets without a coastal sense of irony, the shiny diaper pins (pins -- get it?) actually conveying something to their peers. They pursue goals that require ungodly work but have little logical reward in this day and age. A college scholarship, perhaps, but not a $35 million contract, and not much TV time either.

Still, in the northernmost part of the state, you could do worse than drop the name of Mark Schwab, a four-timer from the mid-1980s. You might even get some conversation out of a mention of Gerald (Germ) Leeman, a three-timer who won a silver medal at the 1948 Olympics. Both of them, believe it or not, came from Osage (pop. 3,451; CITY OF MAPLES). No doubt you've flown over it.