Four Divided By Three

UCLA guard Arron Afflalo can close his eyes and conjure every detail, a vision from a childhood spent launching imaginary three-pointers in his family's Compton, Calif., living room: Monday night, final seconds, down two, 50,000 fans watching in the seats and millions more on TV. In his mind's eye he curls off a screen, catches a pass on the wing, jab-steps to freeze his defender and unspools a rainbow three pregnant with possibility. Splash. "Man, that would be so sweet," Afflalo says, opening his eyes and smiling at the thought of UCLA's 12th national title. "But I wouldn't be surprised. I'd expect it to go in. You have to think that way if you're going to make a shot like that."

If history is any guide, no lead will be safe at this week's Final Four in Atlanta -- where the Bruins will join Ohio State, Florida and Georgetown -- due mainly to the three-point line, the ubiquitous arc that's celebrating its 20th anniversary in college basketball this season. "It's the single greatest equalizer in any sport, collegiate or professional," says Florida coach Billy Donovan, citing the sheer magnitude of the benefits: an extra point worth far more than, say, a gridiron extra point. "It's the equivalent of telling a football team: If you throw for a touchdown, you'll get nine points, but if you run for it, you'll get six," he says. (Add one more reason why Donovan has won over pigskin-addled Gators fans: He speaks their language.)

No figure symbolizes the past and present of the college three-pointer more than Billy D, who's such an arc acolyte that it's a wonder he didn't name one of his sons Trey. It was Donovan the point guard who rode the three with Rick Pitino's groundbreaking Providence outfit to the Final Four in 1987, the line's first year, and it's Donovan the coach whose Gators will arrive in Atlanta as both the Final Four's most accurate three-point shooters (40.5%) and the nation's second-best defenders against the three (limiting foes to 29.1%). The jerseys may say florida, but the philosophy is pure Slick Rick. "Coach Pitino was so far ahead of his time," Donovan says. "A lot of coaches were opposed to the three-pointer [when it was introduced], but he was the first to understand the importance of not only taking the shot but guarding against it."

Nearly all of the skeptics have since been converted, however, and over the past 20 years the three-pointer has revolutionized college hoops, for better or for worse. Since 1986-87 its use has skyrocketed from one out of every 6.4 field goal attempts to a record high one of every 2.9 this season entering the NCAA tournament. What's more, those numbers have only increased during this year's NCAAs. The teams in the field of 65 have attempted even more three-pointers (a combined 38.2 per game, compared with 37.7 during the regular season) and made slightly more of them (13.5, up from 13.2) for a higher percentage (35.4%, up from 34.9%).

"The college game has changed," says Ohio State coach Thad Matta. "Now you have four and sometimes five guys on the floor who can shoot the three." It's enough to remind everyone that the college three-pointer is far too easy, a 19'9" chip shot that detractors say is about as hard to hit as a 250-foot home run. But until the NCAA Rules Committee votes in May on a proposal to extend the line (most likely to the 20'6 1/4" international distance), the college trey will remain a minimal challenge that nearly any player can meet. (Coaches are a conservative lot, though: Among the Final Four bosses, only Donovan and Georgetown's John Thompson III would like to see the line moved back.)

Not surprisingly the Gators' chances for a historic double this week -- they're aiming to become only the second champion to repeat since 1973 -- will depend heavily on the triple. Last year guard Lee Humphrey sealed Florida's national semifinal win over George Mason and its title-game victory against UCLA by drilling a combined eight second-half threes in the two games, joining such storied Final Four sharpshooters as Duke's Mike Dunleavy Jr. (whose three treys in 45 seconds sank Arizona in the 2001 final) and Michigan's Glen Rice (whose five threes staggered Seton Hall in the '89 final). But the three-pointer can cut both ways: Who can forget the Final Four-record 40 three-pointers that Illinois hoisted in its '05 title-game loss to North Carolina? The Illini made 12 (a 30% strike rate) and missed all five attempts in the final three minutes before falling 75-70.

With so much riding on the long ball, it's worth asking: What's your three-point stance? South Regional champion Ohio State takes a greater portion of its field goal attempts from three-point range (36.8%) than any other Final Four team, and if you stumbled upon the end of a Buckeyes practice, you might think they're a bunch of unrepentant gunners. Before they hit the showers the team's top outside shooters -- Ron Lewis, Ivan Harris, Jamar Butler and Daequan Cook -- all have to "get their Bird," their term for hitting a perfectly swished three-pointer from the top of the key. (The expression refers to Larry Bird, who ended his practices the same way.) "If we're feeling good that day we'll get more than one in," says Lewis, who has made 12 of 26 threes during the tournament, including the stunning last-second equalizer that sent Ohio State's second-round game against Xavier into overtime.

But if you look more closely, the Buckeyes are far less reliant on the trey than they were last season, when 40.1% of their shots came from the arc. The difference? Seven-foot freshman center Greg Oden, who provides an improved low-post scoring threat, and freshman point guard Mike Conley Jr., a master at penetrating into the lane. "The whole key is blending," says assistant coach John Groce. "We were predominantly a three-point-shooting team last year, but [Oden and Conley] have afforded us the luxury of having a balance in our attack, which makes us harder to guard." That inside threat worked wonders last Saturday, when Oden's second-half assertiveness helped free Butler and Lewis for the three-pointers that broke open the game against Memphis and allowed OSU to cruise to a 92-76 victory.

When the Buckeyes' coaches scout an opponent, one of the first things they'll do is log on to kenpom.com, a Moneyball-type statistical database that, among other things, breaks down a team's ability to score from three-point range, two-point range and the free throw line. What they'll see in national semifinal foe Georgetown will strike them as a simulacrum of their own team. The Hoyas shoot the three more often than Florida or UCLA, but the rise of fearsome big men Roy Hibbert and Jeff Green over the past two years has caused Georgetown's reliance on the trey to plunge from 42.6% of their shots in 2005 to 34.6% this season.

Compared with most coaches, JT3 has a novel approach to the three-pointer: He's convinced that the 19'9" line has conditioned players to underestimate their ability to hit, say, a 22-foot jumper. "If you watch tapes of older games [from the days before the three-point line], people are shooting from significantly farther away than they are now," says Thompson. "We tell our guys, 'Back up. You can make a much longer shot than that. But you've been trained to stand right here [at 19'9"].'" Thompson would prefer that his players take an open 22-footer over a more closely guarded 20-footer, and he has even considered laying down an extended three-point line on the Hoyas' practice courts to raise their confidence when it comes to shooting the deeper three.

Then again, not all the Hoyas need to be convinced. Junior guard Jonathan Wallace, Georgetown's most lethal three-point threat (48.6%), says he feels comfortable shooting "from at least NBA range [23'9"] and maybe a step behind it" -- a boast that he backed up with supersized cojones on Sunday by nailing a game-tying trey with 31 seconds left in regulation during the Hoyas' thrilling 96-84 OT win against North Carolina.

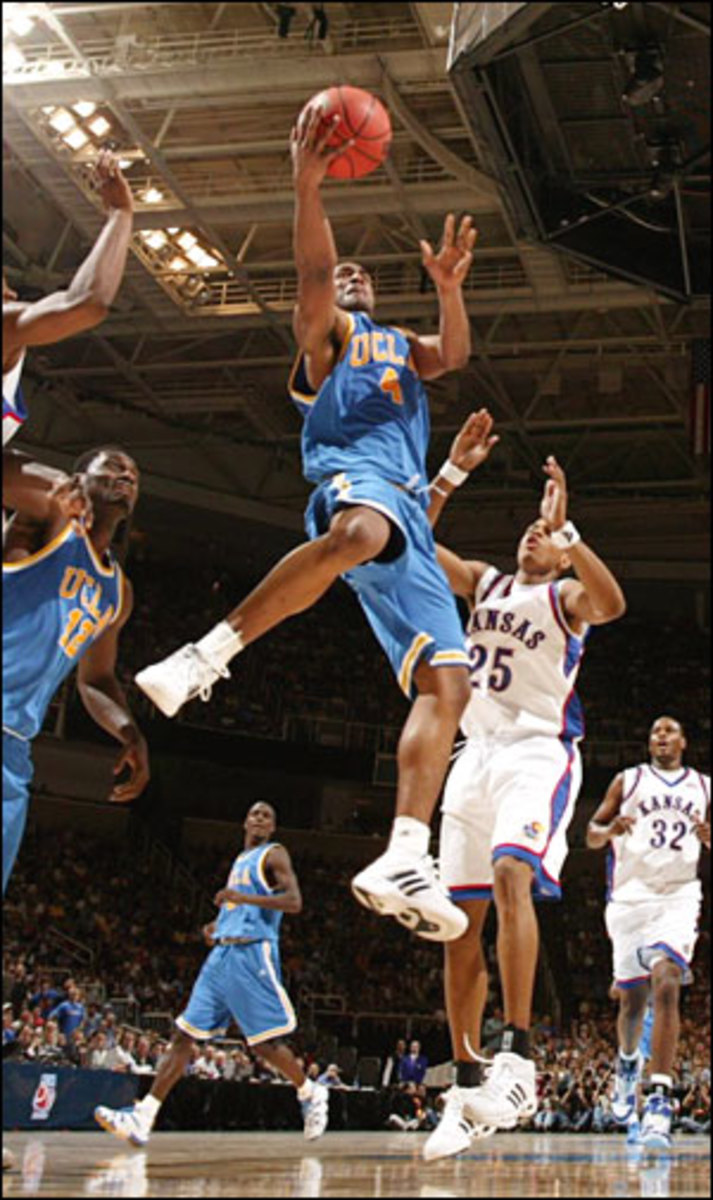

In the other national semifinal between UCLA and Florida, the battle around the three-point line will be fascinating from a defensive perspective. Only one team in the NCAA tournament (Duke) allowed opponents to take a lower percentage of their field goal attempts from three-point range this season than the Bruins (27.0%), whom coach Ben Howland has rebuilt in four short years on the basis of gear-grinding defense. How does Howland's flytrap D take away the three? For one thing, the UCLA players -- all of them, really, but Afflalo and fellow guard Darren Collison in particular -- are dogged on-the-ball defenders, equally adept at switching out on shooters behind perimeter screens and preventing dribble penetration that leads to kick-out threes.

But if the ball does enter the lane, the Bruins are often asked to do something that's counterintuitive. "You've got to have your players stay home and not play help defense," says Howland. "That's going against their instinct, but if you really want to stop the three, you can't get drawn into helping out. So many teams get an open look at a three late in the game, and you say to yourself, 'Why did they leave that kid?' Well, it's because his defender went and helped out instead of staying with his man."

On offense UCLA wants to shoot enough three-pointers to keep defenses from sagging, but it's revealing that the Bruins' most prolific three-point gunner -- Afflalo, who has taken nearly twice as many treys this season as any of his teammates -- doesn't consider himself one. "I'm a scorer who can shoot the three, but I'd rather get into the paint," says Afflalo, who's merely respectable from three-point range, at 37.7%.

The Bruins do have other deep threats in guards Collison and Michael Roll and forward Josh Shipp, but they'll have their work cut for them against Florida, which owns that stingy three-point defense for a reason, as UCLA discovered in last year's 73-57 title game loss (when it shot just 3 for 17 from long range). "We've really put a focus on taking away threes, and that's a credit to our team," says assistant coach Donnie Jones, noting that the Gators' top big men, 6'11" Joakim Noah and 6'10" Al Horford, are agile enough to challenge guards on the perimeter. "You also have to understand who the shooters are and force them to drive. We're not giving you threes, and if we do, you're going to take them two or three steps out of your range."

When the Gators have the ball, they try to maximize their frontcourt supremacy by establishing their inside game first. Only then do they look for the three-pointer, most often from point guard Taurean Green (a 40.4% three-point shooter) and Humphrey (45.5%). So deadly was the marksman known as Humpty in Sunday's 85-77 Midwest Regional final victory over Oregon that he caused an 11-minute delay when one of his seven treys literally broke the net. "He's on fire," cracked teammate Corey Brewer amid the postgame revelry. "Nets are coming off! Go get ladders!"

Go get ladders. It's a request that these transcendent Gators have grown accustomed to making over the past two seasons as they've celebrated two regional final wins, two SEC tournament crowns, a regular-season league championship and, of course, a national title. As they stand at the gates of the college basketball pantheon, it says here that Billy D's boys have the teamwork, the experience and, not least, the three-point superiority to cut down the nets again.

With a shooter like Humpty, though, scissors may not even be necessary.