Is sport an art?

Sport is not considered art. Instead, it is invariably dismissed as something lesser -- even something rather more vulgar -- than the more traditional performance activities.

Now, Gary Walters, the athletic director at Princeton has spoken out that sport should be granted equal educational prestige with the likes of drama and art and music. "Is it time," he asks, "that the educational-athletic experience on our playing fields be accorded the same ... academic respect as the arts?"

Walters validates his advocacy with these credentials: He went to the Final Four as playmaker on BillBradley's final team. He later coached in the big time Big East, and then he became an athletic director at his alma mater in the Ivy League. He was chairman of the national Division I basketball committee this year, the maestro of March Madness. This is all to say that he brings the broadest perspective to college sports, and it mightily irritates Walters that sport is only considered a "distant cousin" to the arts.

Well, apart from simply being so sweaty, I think sport has suffered in comparison with the arts -- or, should I say, the other arts -- because it is founded on trying to win. Artists are not supposed to be competitive. They are expected to be above that. We always hear "art for art's sake." Nobody ever says "sport for sport's sake."

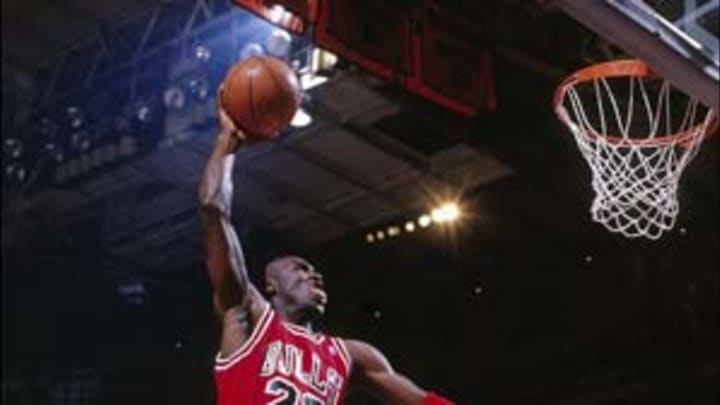

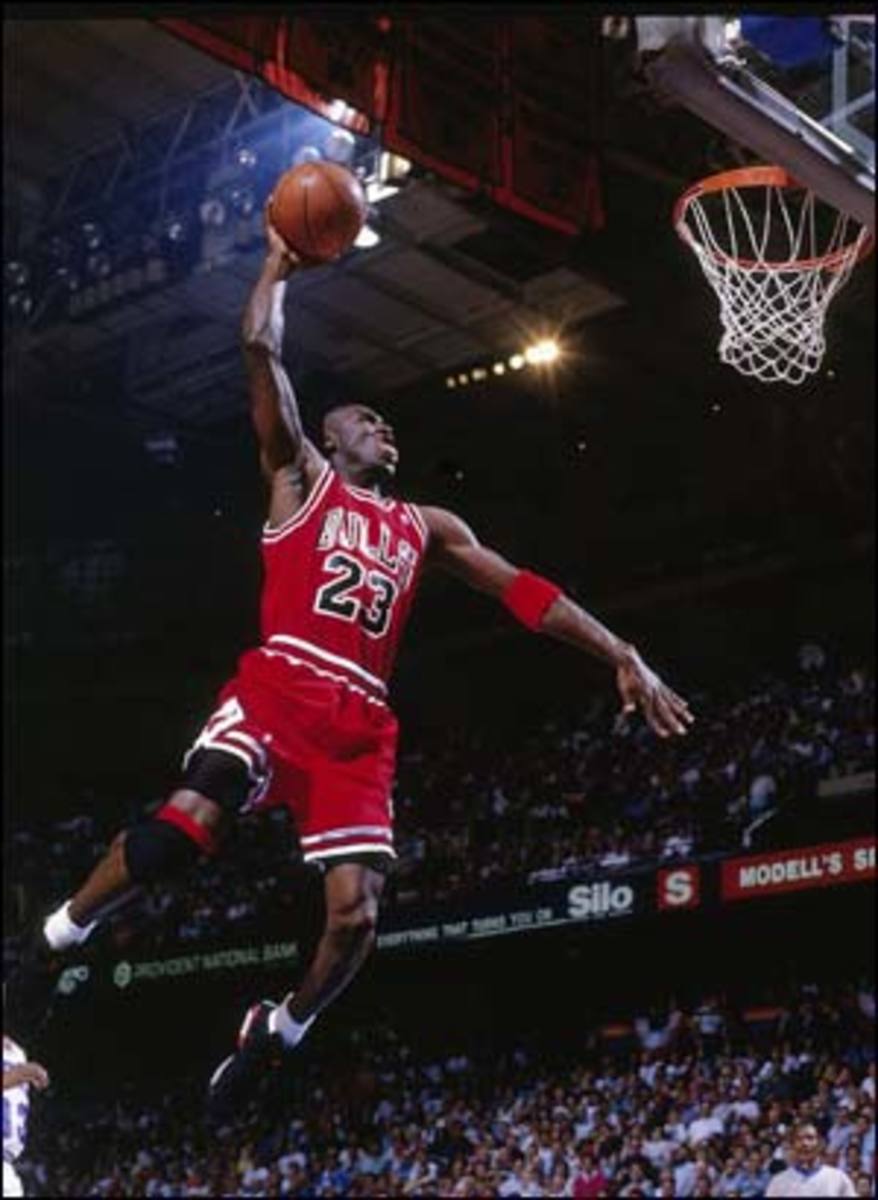

I also believe that sport has suffered because, until recently, athletic performance could not be preserved. What we accepted as great art -- whether book, script, painting, symphony -- is that which could be saved and savored. But the performances of the athletic artists who ran and jumped and wrestled were gone with the wind. Now, however, we can study the grace of the athlete on film, so a double play can be considered as pretty as any pas de deux. Or, please, is not what we saw Michael Jordan do every bit as artistic as what we saw Mikhail Baryshnikov do?

Of course, in the academic world -- precisely the place where art is defined and certified -- sport is its own worst enemy. Its corruption in college diminishes makes it all seem so grubby. But just because so many substitute students are shoe-horned into colleges as athletes and then kept eligible academically through various deceits, the intrinsic essence of the athlete playing his game should not be affected. As Walters argues: "Athletic competition nourishes our collective souls and contributes to the holistic education of the total person in the same manner as the arts."

Certainly, there remains a huge double standard in college. Why can a young musician major in music, a young actor major in drama, but a young football player can't major in football? That not only strikes me as unfair, but it encourages the hypocrisy that contributes to the situation where those hidebound defenders of the artistic faith can take delight in looking down their noses at sports. So, yes, Walters' argument makes for fair game: is sport one of the arts? Or: just because you can bet on something, does that disqualify it as a thing of beauty?