Welcome to L.A.

LOS ANGELES -- Joe Torre is leaning back on a swiveling chair in a quaint boardroom tucked away in the Club Level of Dodger Stadium. As he takes off his blue Dodgers hat and places it on the wooden table in front of him, he looks down at the Dodgers uniform he's wearing over his light blue shirt and tie and smiles.

After being introduced as the team's new manager during a news conference in center field on an overcast morning and being led through a Hollywood-style press line in front of the stadium's outfield wall, Torre is still getting used to his new wardrobe.

"It is [strange]," he says. "You look at this uniform and I remember when it was Brooklyn and when [the number] became red and they put the number on the front. These things are very vivid to me."

Torre remembers the Dodgers well, even if he didn't always feel the same allegiance as his friends and classmates at Brooklyn's St. Francis Prep, where he played third base for the all-boys Catholic high school that also spawned Vince Lombardi.

"I was a Giants fan," he says. "So this is surreal."

The framed black-and-white pictures lining the walls around Torre tell the story of the organization, each one taking him back to his roots in Kings County. There's a picture of Dwight D. Eisenhower throwing out the first pitch of the 1953 World Series, Johnny Podres getting mobbed by his teammates after the 1955 World Series and Don Drysdale pitching at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum during the 1959 World Series.

"I played at the Coliseum -- just for one series, thank God," he says. "Not being a pull hitter, it was brutal for me. I think I had whiplash trying to hit the ball over that screen. I think I finally shaved the screen coming down off [Sandy] Koufax one time for a single. There's always been something different about the people that have worn this uniform."

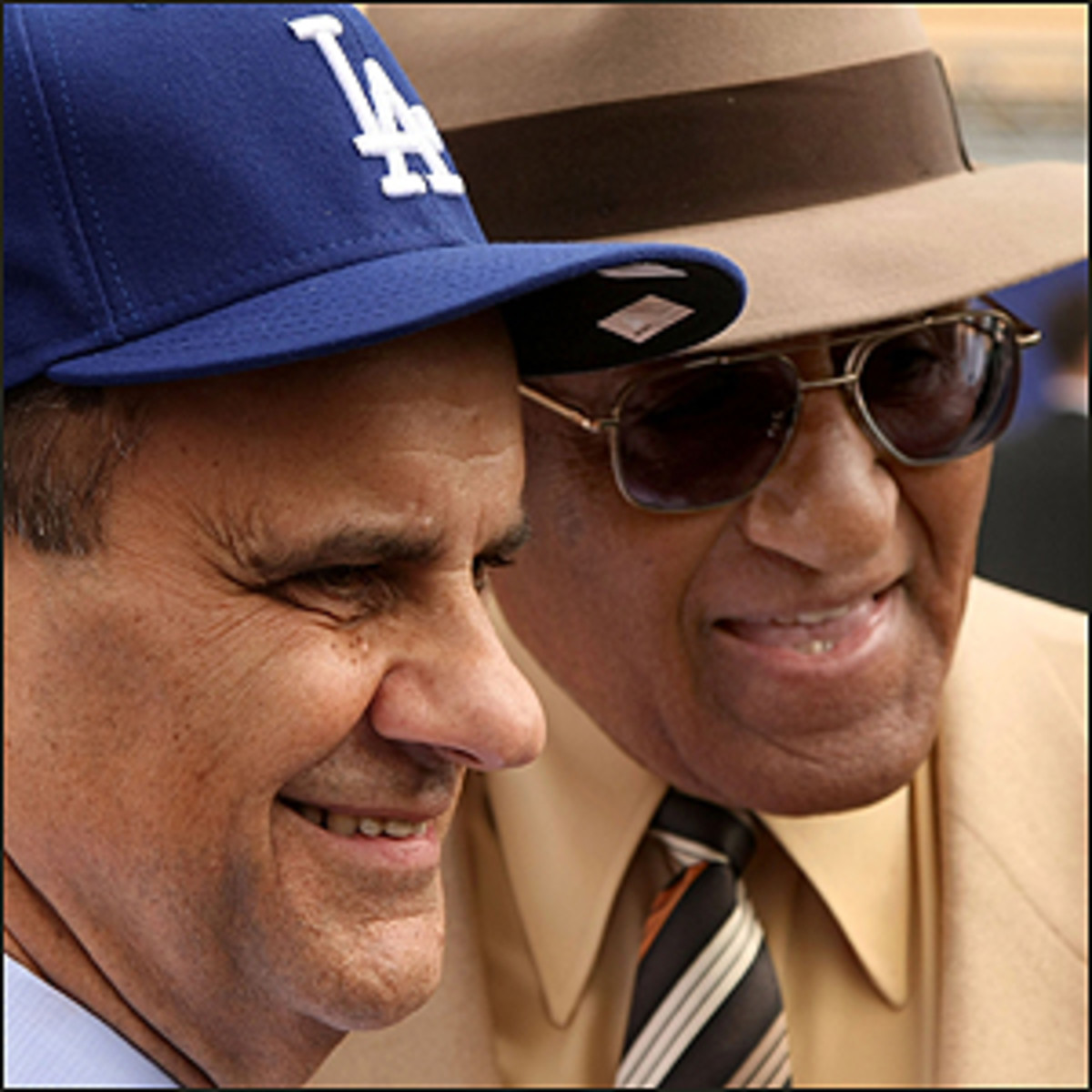

While Torre still gets used to wearing his new uniform -- so new that his wife, Ali, had to take the stickers off the brim of Torre's hat -- there was an unmistakable homage to the Dodgers' past with the hiring of a "Brooklyn kid" as the 26th manager in franchise history. The fact was not lost on the many Dodgers legends seated in front of the podium when Torre was introduced.

Nearly 50 years ago this week the Dodgers held another news conference about three miles south of Chavez Ravine at the Statler Hotel in downtown Los Angeles announcing that the team was moving from New York to Southern California. A huge sign set up behind Walter O'Malley proclaimed it, "The Greatest Catch in Baseball," and after the Dodgers had advanced to the World Series in five of the previous 10 seasons, winning it all in 1955, it was hard to argue with that.

A half century later, Los Angeles is hoping another New York import with a similarly impressive resume will be able to turn around the fortunes of a franchise that hasn't won a playoff series in nearly 20 years.

"The excitement in the city is very similar," said Don Newcombe, who was one of the Dodgers greats who came to Los Angeles from Brooklyn after the 1957 season. "Part of the excitement stems from wanting to be associated with a winner. In professional sports you have to win. Show me a good loser and I'll show you someone who doesn't have a job. That's what Leo Durocher used to say. We've got to win as a team and he has the credentials to help us win and that's the bottom line."

Towards the end of his tenure in New York, Torre learned the hard way that winning was the bottom line. Despite leading the Yankees to the postseason in each of his 12 seasons in the Bronx, including winning the World Series in four of his first five, he was forced to fly down to Tampa, Fla., two weeks ago in hopes of saving his job. He cut ties with the Yanks later that day after being offered a one-year deal with a pay cut and postseason incentives -- a proposal he considered a slap in the face.

Interestingly, Torre began to think that his days as the Yankees' manager were numbered three years ago after the Red Sox came back from a 3-0 deficit and won the ALCS. Instead of being depressed by the outcome, however, he felt an odd sense of fairness about it all. After winning so much, so early, most of it coming at the expense of the Red Sox, it was only right that Boston would finally get its day in the sun and eventually prompt Torre to leave New York.

"I remember the vision I had of Tim Wakefield walking of the field after giving up the home run to Aaron Boone [in Game 7 of the 2003 ALCS]. Then the following year we're three outs away from going back to the World Series and then we lose four straight to the Red Sox," says Torre. "That's when I felt things were starting to separate in terms of my stay in New York and leaving. But it was amazing experience to see Wakefield walk off the field the year before as the loser and then watch him again the following year as a winner. I didn't want to lose but I wished him luck. I just thought it was some kind of justice that was being performed."

Justice surely wasn't a word Torre would use to describe the way he was treated his final three seasons in New York when he lived year-to-year, never really knowing where he stood with George Steinbrenner. The distractions it cast over him and the team may have been a factor in three straight first-round exits and were the biggest reason he refused to accept a one-year deal that would have made him a lame duck manager again.

"Maybe I'm overly sensitive but my last three years in New York were turbulent," he says. "There were three years where I didn't know if I wanted to manage [the Yankees] because I wasn't sure if they wanted me to manage. I just needed to know if they wanted me to manage. Last year, hell, five minutes before our [end-of-season] press conference George said he wanted me to manage the club. At that point I knew this ice wasn't very thick."

For the first time in about three years, Torre will enter the upcoming season knowing his long-term status and not having to worry about an owner threatening to fire him or his coaches if they don't live up to expectations.

"It makes me feel better about the job I do," says Torre. "There are a lot of times if you lose a game people will say you weren't paying attention or say why didn't you do this or do that. I like people to trust what I do. I like to believe I know what I'm doing. It helps me to represent an organization and have the organization support me."