Victim of expectations

Yawn.

Then ... four seconds into his career playing against men, an 18-year-old Eric Lindros hit MacInnis with a check that gave the onlookers a bigger jolt than any take-out double-double of Tim Horton's coffee. You know those collapsible paper skeletons that hang on the classroom doors of elementary school around Halloween? Well, that's how MacInnis crumpled to the ice. In sections.

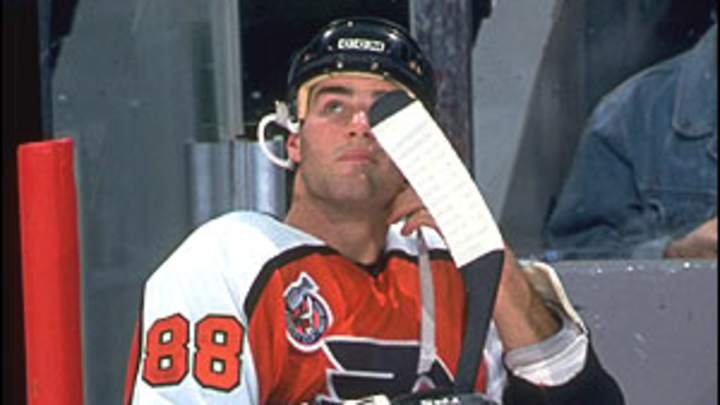

At that precise moment, there were people in the stands -- me, included -- who believed that Lindros would have as much impact on hockey as he had had on MacInnis. This was easy. This impossibly handsome kid with the square jaw and twinkling eyes would not be the Next One, as he had been anointed in junior hockey, but the First One, a wholly original player who was different, although not necessarily better, than anyone who had come before him. He was a 6-foot-4, 235-pound package of size and strength and dangle, a combination that would change the hockey paradigm, would push the borders as easily as he pushed around an unsuspecting all-star defenseman.

The revolution was over that sultry morning. Lindros won.

Lindros was set to formally announce his retirement at a press conference in London, Ontario, on Thursday, 16 years after leaving that indelible impression on anyone who was there. The revolution fizzled. The irony is that after the NHL actually took some halting steps to revolutionize itself after the lockout, there really was no place in the game for him, a first-rate center who had been reduced to skating the right wing for the Dallas Stars.

Ultimately Lindros's career was a victim not of his laundry list of injuries (especially concussions) or the ravages of creeping age (he quits at an old 34) but of expectations. Any player who scores 372 goals, who plays in three Olympics, who wins the Hart and Lester B. Trophies, who averages more than a point a game despite a surfeit of injuries, should be judged to have been a wild success. Instead, Lindros has widely been viewed as falling short of his promise. He was finished by the pernicious hat trick of woulda, coulda, shoulda -- an affliction that strikes only those among us who have been graced with uncommon talent. Lindros was measured, often unfairly, on a scale that was even more out-sized than his skills.

Even before the moment at the draft in 1992 when Quebec Nordiques owner Marcel Aubut demonstrated that he was not the kind of man to take yes for an answer and traded the young phenom to both the Flyers and the Rangers, Lindros always seemed to be digging out of some controversy. No player in recent memory has ended up being buried under a greater avalanche of gossip and gawking by a hockey world that seemingly took a proprietary interest in Carl and Bonnie Lindros' son. There was so much clutter surrounding Lindros that sometimes you needed a machete to hack your way through. Some of it was his doing -- his decision not to play in Quebec after being the first player selected in the 1991 draft, for example -- but most of it was not, such as Team Canada (and Philadelphia) general manager Bob Clarke's decision to make Lindros captain of the 1998 Olympic team even though Wayne Gretzky, Ray Bourque and Steve Yzerman were among his teammates.

For a seven-year-period, mostly in the NHL's dead puck era, Lindros averaged a creditable 1.4 points per game -- an arc that rivals the accomplishments of the Montreal Canadiens' fabled Guy Lafleur. But it never seemed to be about what Lindros accomplished on the ice -- including winning the Hart and Pearson Trophies in 1995 -- but what he didn't do. Sometimes it mattered less who he was than who he wasn't.

Lindros was not the Next One. He was not Gretzky. He was not Mario Lemieux. And, no, unlike Lafleur, he didn't win a Stanley Cup. In fact, his biggest failing as a player might have occurred the year he came closest: 1997. Lindros, then the Flyers' captain, slipped out of a back door at Joe Louis Arena after practice and was not available to respond to coach Terry Murray's assessment that Philadelphia's three-games-to-none deficit in the final against Detroit was "a choking situation." Forced to comment in Lindros's absence, veteran defenseman Eric Desjardins uttered the memorable, "Ai, yi, yi, yi, yi." And although Lindros had an NHL-best 26 points in the Flyers' 19 playoff games that spring, he is probably best remembered for not being in the dressing room to respond to Murray's use of the c-word. Inadvertently, Desjardins had summed up the perception of Lindros from that moment on: more ai, yi, yi than awe.

Now that Lindros is done, you can deconstruct his injuries one more time and project what his numbers might have been if he had been healthy. (He missed the 2000-01 season and played more than 70 games just four times in his career.) You can revisit his tragic flaw of sometimes rushing the puck with his head down, which was not hubris as much as bad habit carried over from youth when he was so much bigger than everyone, a mistake New Jersey defenseman Scott Stevens reminded him of with a shoulder to the jaw in the 2000 playoffs. (Lindros would never score another playoff goal after that concussion, his sixth.) But along the way, Lindros also sprinkled in four 40-goal seasons, added more than a point-per-game average in the playoffs and played a pivotal role in turning John LeClair into one of the top left wings of his generation.

Lindros, who when he let his guard down was delightful company, will stay in hockey with the players association, which should benefit from his role as ombudsman. (Maybe he can help take the union in a new direction, one that includes more concern for workplace safety issues.) If he has any regrets about having reached the end as a player, well, he shouldn't.

No, Lindros never earned a seat at the Big Guy's table with Gordie, the Rocket, Orr, Gretzky and Mario. But his career can't ever be dismissed as a failure simply because the world set a goal that exceeded his grasp. To borrow from lapsed hockey writer William Shakespeare, the fault was not in our star ... but in ourselves.