A Fight Between Friends

You ready?"

The late-night bull session had lasted more than three hours, and now the top two basketball recruits in the land -- the center from Oregon and the guard from West Virginia -- exchanged assassins' smiles over the lukewarm remnants of a pizza in their room at The James hotel in Chicago. It was nearly 4 a.m. on April 4, a few hours after Kevin Love and O.J. Mayo had been named MVPs of their respective teams at the Roundball Classic high school all-star game, and the two friends had traded thousands of words outlining their common dreams: forging Hall of Fame careers, winning NCAA and NBA titles and, as Love recalls with a laugh, "whipping each other's asses when we get to L.A."

But no two words were as deliciously charged as the ones Love spoke to end the evening: "You ready?"

"Man, what do you think?" Mayo replied, cutting the lights. "I'm always ready."

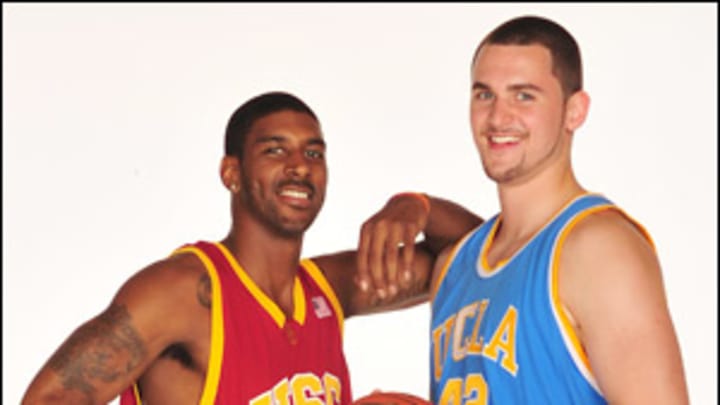

If the story of last year's regular season was Greg Oden and Kevin Durant, transcendent freshmen who flashed like comets through the college game, then the story entering this season is UCLA's Love and USC's Mayo -- with an added kick. After all, Oden and Durant occupied distinct orbits, playing in different regions for teams that never met on the court. Imagine that this time the most-talked-about freshmen play in the same city (Los Angeles) for bitter rivals (the Bruins and the Trojans) in the nation's top conference (the Pac-10). Imagine that their teams will face each other at least twice. Imagine that they are longtime pals who've been battling like a latter-day Larry and Magic ever since they first met in the eighth-grade AAU national championship game.

Imagine, not least of all, the City of Angels turning into a college sports town. "Now that Kobe doesn't know what he's doing, they're going to own the city," says Sonny Vaccaro, the recently retired grassroots hoops guru and founder of the ABCD camps. "You're going to start seeing the Denzels and the Jacks at college games. I can sense it already: [UCLA-USC] will be a major ticket."

To hear some pundits, in fact, Mayo versus Love represents nothing less than the Clash of Civilizations, college basketball division. It's East versus West; scorer versus passer; new school versus old school; city game versus suburban ball; the 'hood versus Mount Hood. Spend some time with the principals, however, and they seem more like kindred spirits, two more SoCal freshmen with iPhones on their belts, girls on their minds and In-N-Out burgers in their mouths. "We have that common respect," says Love. "People are like, 'O.J.'s way more this, and you're way more that,' and I'm like, 'Come on, man. We might come from different backgrounds, but we are very similar.' "

If one player gets his way, the slogan of the upcoming season will be Love and Basketball. If the other gets his, he'll happily turn every arena into the Mayo Clinic. So when Love and Mayo met again last summer -- in a pickup game at UCLA's Student Activities Center with a group that included NBA stars Kevin Garnett, Baron Davis and Sam Cassell -- the anticipation in the air was as palpable as their pregame handshake-hug. "O.K., we're ready now," Love told him. "Let's go to work."

*****

Ovinton J'Anthony Mayo was 11 years old when he started playing chess at Billy Scott's barbershop, a neighborhood gathering spot in Huntington, W. Va. The game fascinated him almost as much as the one that would start earning him national attention (and his first picture in SI) as a seventh-grader in 2002. Still does, too. "I try to make basketball like a chess game," says Mayo, a 6' 5", 205-pound combo guard. "If there's one mistake, one bad move, you want to expose it -- on the defensive end, too. It's about knowing what's going on three moves ahead of your opponents."

In terms of scoring, Mayo could play a role for USC that's similar to the one Durant, the first freshman to win player of the year, filled with Texas. The Trojans have one of the top recruiting classes, but the roster is painfully young overall -- coach Tim Floyd lost his top three scorers from last season -- and Mayo's 32-point outburst in the 96-81 upset loss to Mercer last Saturday may become the norm. Mayo doesn't possess Durant's Plastic Man length or off-the-charts hoops sense, but unlike Durant, a forward who sometimes struggled to receive the ball in the Longhorns' offense, Mayo should find it easier to latch onto the rock as a lead guard.

And once he does, Mayo slashes like a bishop, jukes like a knight and covers the court with the majesty of a queen. "I think he can play [point guard or shooting guard] in the NBA," says Floyd, who adds that none of the first-round picks he coached on the Chicago Bulls (including Elton Brand, Jamal Crawford and Eddy Curry) made a better first impression on him than Mayo did in practice. "O.J. can post, he can beat you off the dribble, he can play out of the screen-and-roll with poise," says Floyd. "He can make a perimeter jump shot, he has a midrange game, and he passes the ball well. And he can really defend."

The biggest question is whether Mayo will shoot USC out of games. At the McDonald's All-American game in Louisville in March, Mayo went 4 for 17, clanging the potential game-winner in the final seconds. But Mayo says he has enough confidence to keep firing, a lesson his idol, Kobe Bryant, reinforced last summer during the final moments of a deadlocked pickup game in L.A. Mayo had made three straight shots, but he passed up the deciding jumper, feeding an open shooter instead. Mayo's teammate missed; Bryant's team won. Afterward, Bryant pulled Mayo aside and offered some advice: "When you've got it going like that, take the shot!"

"What if he's open?" replied Mayo.

"It's different if you're throwing it to a player you feel can make that shot," said Bryant. "But throwing it to him just because he's open doesn't give the team the best shot of winning."

Mayo nodded. "It kind of made sense," he says. Translation: You're crazy if you think I'm passing in crunch time this season.

Love can put up big numbers, too. UCLA coach Ben Howland thinks the 6' 9" 271-pounder from Lake Oswego (Ore.) High has the chance to become the first freshman in Bruins history to average a double double in points and rebounds. Love can work the low blocks and step out to shoot the occasional three-pointer, but what makes him unique is his ability to whistle 50-foot outlet passes to fast-breaking guards -- a skill that has earned him comparisons with the best-passing big men of all time, players like Wes Unseld and Bill Walton. "He's going to be one of the best outlet passers people have seen in quite a while," says Howland. "He has great strength, and he can really fire the ball."

In some ways Love's profile resembles the one Oden had with Ohio State last season. Love may be three inches shorter, but like Oden, he's a throwback big man with enough talent surrounding him to challenge for a national title. And developing chemistry with his teammates shouldn't be an issue. In Love's first games alongside junior guard Darren Collison at a camp in New Orleans last summer, he fired court-length chest and overhead passes that Collison turned into layups without taking a dribble. "We just started connecting," Collison says. "I use my speed to get all the way down the court, and as soon as he gets the rebound he likes to throw it. We're talking full-court distance." Afterward, NBA scouts were stunned to discover that it was the first time the two had played together.

Best of all, Love's arrival should herald UCLA's transformation from a gear-grinding half-court attack into the fast-breaking college version of -- dare we say it? -- Showtime. "No matter what you do, you can't stop it," says Love, "because even if I hit my guy at half-court, the ball travels faster than anybody's going to run. My teammates will be there filling the lane, and it's going to be a three-on-two or two-on-one situation. Even if they send their players back [downcourt], they're never going to get an offensive rebound."

Love certainly isn't lacking in confidence. In the space of an hour he stakes a claim that would seem preposterous for any other collegiate post player ("I feel like I'm the best passer in the country"); apologizes in advance to the defenders his passes will bamboozle ("You'll see me laughing on the court sometimes this year. It's funny to me. I'm almost playing a game with them"); and expresses his desire to take the last shot when games are on the line ("I want everything to be riding on my shoulders").

If everything goes according to plan, Love explains, the acclaim will take care of itself. "When it comes to Los Angeles, there's Kobe Bryant, and then there's Kevin Love and O.J. Mayo," he says, lowering his right hand from eye level to chin level. "We're trying to be two young princes, big stars of L.A. But that comes with winning and playing well."

*****

The tale is already part of basketball lore. In November 2005 Tim Floyd welcomed an unexpected visitor to the USC basketball office whom he swears he had never met before. As Floyd tells it, the stranger asked him, "How would you like the chance to coach O.J. Mayo, the Number 1 prospect in the country?"

"Who wouldn't?" replied Floyd, who hadn't sent Mayo a single recruiting letter. "Who are you?"

"Rodney Guillory."

"Why would this young man listen to you?" Floyd asked.

"Because," said Guillory, a basketball event promoter in Los Angeles, "I've been his mentor since the seventh grade." They talked for 45 minutes, and that night Floyd took a call from Mayo. They discussed Mayo's interest in building USC into a national program while playing in the nation's second-largest media market. And though he had never met Floyd, Mayo committed to playing for the Trojans. Right on the phone.

"Inexplicable," says Floyd, who still can't believe his luck. Two other moments stood out from their conversation that night. According to the coach, Mayo refused to give Floyd his cell number ("I'll call you," Mayo said) and told Floyd that he would help take care of USC's recruiting (Mayo persuaded Davon Jefferson, a blue-chip forward from Lynwood, Calif., to join him). As the stories circulated across the country, Floyd's colleagues shook their heads in disbelief. "I found the whole thing comical, like something out of Hollywood," says one major-college coach. "But it certainly makes you wonder where all this is heading."

At a time when the NCAA is investigating the USC football program about potential violations involving former running back Reggie Bush and an L.A. marketing rep, questions have been raised about Mayo's relationship with Guillory. (In 2000 the NCAA labeled Guillory an agent's representative and suspended two basketball players, including USC's Jeff Trepagnier, for nine games of the 2000-01 season after they accepted plane tickets from Guillory.) When asked about Guillory's reputation, Floyd said the athletic department had conducted a background check, and he wasn't concerned about the promoter's ties to Mayo. "Not given what I know about Rodney and what he's learned from his mistake," says Floyd.

Guillory refused an interview request by SI, but Mayo vows that Guillory has done nothing to compromise his eligibility. "He's a great mentor," says Mayo, who lives on campus and has a bicycle instead of a car. "It's good for me to have someone I can trust and talk to here."

Yet Guillory isn't the first adult male to exert heavy influence on Mayo's life. Dwaine Barnes, a family friend whom Mayo calls "my grandfather," was Mayo's longtime summer-league coach and disciplinarian, a buffer who often kept the media at bay during Mayo's rise to national prominence. Barnes steered Mayo and his friend Bill Walker (another elite player now at Kansas State) from Huntington to nearby Ashland, Ky., where they were allowed to play high school ball as seventh- and eighth-graders at Rose Hill Christian School. Then Barnes steered them to North College Hill High near Cincinnati, where they lived with Barnes and won two state championships. "Failure isn't an option for O.J.," says Mayo's mother, Alisha, a medical assistant and single mother, "and Dwaine instilled that in him."

But Barnes's influence slipped as Mayo, only a high school junior, essentially began living alone in an apartment across the street from the North College Hill gym. "I had to figure out on my own what was the right thing to do, and it wasn't easy," Mayo says. "I learned how mistakes get magnified." Mayo was suspended three times during his junior year for various offenses, including fighting and missing class, and the drama only continued when he returned home for his senior season and won another state title with Huntington High. Mayo was suspended for three games in January for bumping a referee, though YouTube clips showed the ref flopping more easily than an Italian soccer player. Then there was a marijuana citation in March that was dismissed when another passenger in the car Mayo was riding in claimed responsibility for the drugs.

Depending on whom you ask in Mayo's world, his decision to attend USC (against the wishes of his mother and Barnes) was either a remarkable act of independence and bravery or the latest in a string of questionable choices. Floyd describes Mayo's move as a liberation. "O.J. was really sheltered from the media by the adults who were in his life until he got here," he says. "There [has been] so much intrigue about him since he burst onto the national scene as a seventh-grader. So when there wasn't a lot of access to him the media painted him with their own brush. I think as people get to know him, they're going to have great respect for him, for his story and for what he's trying to do with his life."

Now that reporters can spend more time with Mayo, Floyd hopes the public will stop hearing the term punk alongside his name and finally see the inquisitive student who scored a 29 on his ACT, who became the first recruit in Floyd's three-year tenure to test out of freshman English, who's taking a weekly three-hour journalism seminar, and who talks about going into real estate and opening restaurants in Huntington and elsewhere after his playing days. "Kind of like what Magic Johnson's doing," explains Mayo.

Mayo says he used to agree with the old Charles Barkley saw that athletes shouldn't be role models. "But now I understand," Mayo says. "I'll get introduced to kids, and they're nervous because they just want to be like you. It teaches you to be a role model for the next generation. Even when your situation looks so messed up -- your father's in jail, your mom's working two jobs just to make sure you've got food -- go to school and make your grades so you can accomplish your dream. And let your mom know: I appreciate what you've done for me."

These days Mayo's relationships with his own loved ones are more complicated than ever. Though he calls Barnes "one of the greatest people ever in my life besides my mom," he and his "grandfather" haven't been on speaking terms since he faxed his letter of intent to USC -- the same letter that Mayo's mother refused to sign. "I told O.J. years ago that as long as he worked hard, he could go to any college he wanted to," says Alisha. "He threw that back in my face on November 15, 2006. But I wasn't going to sign the papers. I thought it was too far [from home] for him. Then his dad went and [signed them]."

O.J.'s father, Kenny Ziegler, a former guard on a state championship team at Huntington High, has been in and out of Mayo's life, serving 20 months in jail for convictions that included drug possession and sexual assault. Ziegler showed up unexpectedly at the Trojans' first public practice on Oct. 12, and his continued presence in Los Angeles has raised concerns that trouble may be brewing between Guillory and Ziegler, with Mayo stuck in the middle. "I want us to have a better relationship. You only have one father," says Mayo, who has occasional contact with Ziegler. "But I'm balancing being a student and an athlete, so it's hard. I'm not sure if he lives out here or not."

Barnes did not respond to SI's interview request. Ziegler could not be reached. For her part Alisha says she still talks to O.J. three times a week and has even grown to like the USC coaches, though she's quick to add that she doesn't trust Guillory. "You can't trust people you don't know," she says. "But if that's what O.J. wants to do, I don't want to put any extra stress on him."

In fact, each day that O.J. Mayo spends in Los Angeles he feels better about his choice to head west. "I had to prove I could go out and make the right decisions, learn from my mistakes and come here to become a man," he says. "I'm not living 30 minutes from my house or having my mom come here and do my laundry and clean my room. It's time to take responsibility and grow up."

*****

Stan Love isn't sure how he'll cope. For more than a decade Kevin's father has captured his son's athletic achievements with his omnipresent video camera. Kevin's perfect game in Little League baseball? On tape. Kevin's dunk that shattered a backboard against Putnam High? On tape. Kevin's 2006 state-title victory against rival Kyle Singler of South Medford High (and now Duke)? On tape. Over the years Stan and his wife, Karen, and their three children -- Collin, Kevin and Emily -- have regularly gathered around the television and watched the highlights that Stan had compiled with care. "We've had a lot of fun with it," says Stan. "I've recorded some unbelievable stuff."

Stan won't be taking his camera to Westwood this season -- he figures the UCLA coaches will send him game tapes -- but he'll be welcomed to Pauley Pavilion in a way that Mayo's father might never be at the Galen Center. "My whole family has been great, but my dad has been the biggest inspiration for me," says Kevin of Stan, who was an All-America forward at Oregon before playing for the NBA's Baltimore Bullets and Los Angeles Lakers from 1971 through '75. Kevin was given his middle name, Wesley, in honor of Unseld, Stan's former Bullets teammate. "The eerie thing is that he's developed a lot of the unique things that Wes had," says Stan. "Especially that outlet."

That was hardly by coincidence. When Kevin was in the fifth grade Stan noticed that his son showed an aptitude for basketball detail, keeping track of how many fouls his opponents had in a game, for instance. Kevin began studying tapes of the NBA's superstars -- Barkley, Bird, Jordan, Kareem, Magic -- and Stan taught him to emulate Walton by securing a rebound, taking one or two dribbles (to draw in defenders) and throwing over the top for a fast break. Later, he challenged Kevin to match a famous Unseld trick in which he would bounce the ball off the backboard at one end of the court, grab it, turn in the air and throw the ball so that it hit the backboard on the other side of the court. Eventually, Kevin did it.

But if Mayo's story limns the dramatic twists of an urban power struggle, Love's sometimes has the suburban dysfunction in a Tom Perrotta novel. "Don't think that just because Kevin grew up in Lake Oswego that he always had a wonderful time," says Stan. The Loves still can't fathom why the stands at Lake Oswego High games were usually half empty until the state playoffs, why out-of-state crowds were more supportive of Kevin than his home fans, or why Kevin would be chosen the Gatorade national high school athlete of the year but didn't win the top athlete honor at his own school. "That hurt Kevin a lot," Stan says.

Ask Kevin to describe his hometown and he brings up the slight on his own. "Lake Oswego's a nice place, but I always got a bad rap there," he says. "The people never really respected me. I always did stuff in the community. But maybe you get hated in your hometown if you succeed."

No moment was more surreal, however, than the skirmish that occurred between Stan and Lake Oswego coach Mark Shoff during Kevin's freshman season. Stan and Shoff had clashed over the playing time of Collin, then a junior forward, and Stan hit the roof after Shoff kept Kevin out of the starting lineup (per school and team policy) the day after he had missed classes with an illness. The next day Stan was spotted posting FIRE SHOFF stickers in the lobby of the Lake Oswego gym. After the coaches notified Kevin of his father's actions, the Loves threatened to transfer Kevin to a rival high school and filed a restraining order against the Lake Oswego coaching staff.

Stan and Karen called publicly for Shoff's dismissal, but Shoff kept his job and coached Kevin to three Oregon player of the year awards without any more confrontations with Kevin's parents. ("It was a case of me being what I like to call a psycho-parent," says Stan Love. "I was out of line, and I apologized to Mark. He did a great job with Kevin.") "Our relationship ended up being a good one," Shoff says of Stan and Karen. "Kevin never disrespected any of our coaches. He was always a player who listened and wanted to get better. He was coachable."

*****

Now that the new season is upon us, it's time to focus on the basketball, to recapture the giddiness that two friends shared in that Chicago hotel room last spring, to anticipate the wondrous talents that Love and Mayo will bring to bear on the college game over the next five months. When they aren't playing on the same court they're two of each other's most ardent supporters. Love says of Mayo, "You could take everybody in the stands and on both teams and try to prevent him from getting into the lane, and he's going to get into that lane." Mayo on Love: "The way he rebounds and throws outlets and gets breaks started, he's a dream big man for a guard who likes to get up and down the floor."

But when USC and UCLA meet on Jan. 19 at Pauley Pavilion and on Feb. 17 at the Galen Center, Mayo and Love will put aside their mutual admiration. They have played each other a half-dozen times since Mayo's outfit beat Love's in that AAU championship.

"O.J.'s never beaten me since," says Love.

"We're going to try and stop that this year," says Mayo.

The game is on. You ready?

A leading soccer journalist and best-selling author, Grant Wahl has been with SI since 1996 and has penned more than three dozen cover stories.