SI Flashback: It's All About The Power

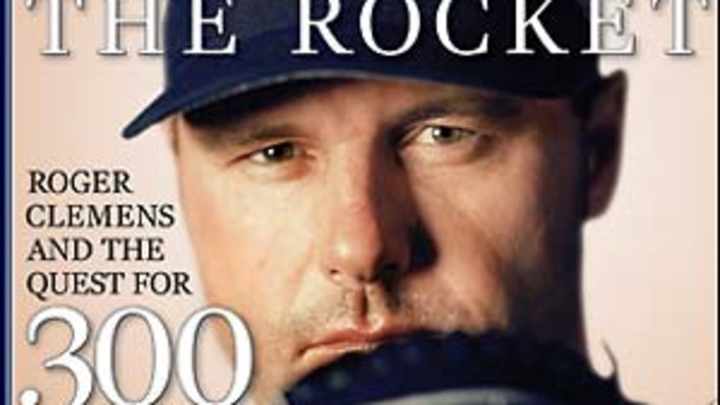

The hard rectangular case is black, with silver steel reinforcements at its edges and a silver steel handle on top. It is the size of a small suitcase. It stands, seemingly obedient, at home and away, day and night, at the foot of the locker of New York Yankees pitcher Roger Clemens. Stenciled in large white figures on the side is the code E-22. On each corner are smaller letters, also stenciled in white: M.I.B.

For four days the case remains shut, serving as an occasional table on which to rest mail, a bottle of water, a baseball cap or some other accoutrement of the mostly mundane life of a starting pitcher.

Everything changes on the fifth day. This is Clemens's day to pitch. Like a soldier wearing camou-flage paint into combat, he sports two days of prickly stubble on his face. He puts on his number 22 game jersey, which he does only on days that he pitches. The jersey is kept under lock and key the rest of the year.

Clack-clack! Clemens throws open the metal clasps to the case. "Everybody look away!" he says. "You'll get blinded! Y'all hitters, you'll forget everything you know about hittin' if you look in."

He sets the case down on its side and pulls it open. What's inside? Opponents want to know. "Do me a favor," Texas Rangers shortstop Alex Rodriguez tells a reporter. "Ask him what drives him."

Teammates also want to know. "There's got to be something in his inner being," says centerfielder Bernie Williams, who recently asked him how he maintained his intensity throughout two decades in the majors. "There's got to be something driving him that's bigger than the game itself."

What's inside a man who turns 41 in two months and who after more than 60,000 pitches still can throw a baseball with a ferocity that even 95 mph fails pitifully to measure? What's inside the greatest pitcher alive? Blasphemy be damned: Maybe his career has been better than those of the dead, too--the communion of diamond saints who never knew integration or the shock-and-awe slugging of today's players.

Clemens's next win will be the 300th of his career, a milestone that only 20 other men have reached. One of them, Tom Seaver, once said he was proudest that he could have finished his career with a 100-game losing streak and still have a winning record.

Seaver was 106 games over .500. Clemens (299-154) is 145 games over .500, better than every 300-game winner but six, all of whom have been dead for more than a quarter century: Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Kid Nichols, John Clarkson and Lefty Grove. Clemens's .660 winning percentage is better than that of every 300-game winner except the long-departed Mathewson and Grove. His relative ERA, which measures a pitcher against his league while considering ballpark factors, is better than those of all 300-game winners except Grove and Walter Johnson.

Clemens's greatest accomplishment, however, is that he is leaving the game exactly as he entered it 19 seasons ago. More than 4,000 innings after his first throw, he remains the consummate power pitcher. He is Dick Clark with a nasty heater. "It's not fair," Mike Borzello, the Yankees' bullpen catcher, tells Clemens.

"What?" Clemens says.

"When you leave, you should be able to give your stuff to somebody else."

The Upper East Side of Manhattan on a Thursday morning is a good place to begin to understand what's inside a man Hollywood would call a stock Texan. Raw, rainy and bleak, its blacktop shimmering wet under a low ceiling of gunmetal gray clouds, this is the New York of antique-silver gelatin prints. The weather is perfect for cabbies, awful for nannies pushing plastic-hooded strollers and of no consequence whatever to aging aces with the stuff young pitchers dream about.

Clemens has gotten his 299th win by beating the Red Sox 4-2 in Boston the previous night. The last of his 100 pitches was a dive-bombing 89-mph splitter to strike out Doug Mirabelli with the tie-breaking run at third base in the sixth inning. That was four pitches after Clemens took a line drive off the back of his pitching hand that ripped the skin off a knuckle, turned his middle finger numb and made the hand swell. Not once did Clemens rub or examine the back of the hand, which already sported a month-old burn mark from an iron. ("What can I say? I'm domesticated," he says.)

Upon striking out Mirabelli, Clemens pumped his fist, let loose a shout, marched into the dugout and yelled, "They're going to have to hit me in the head to get me out!"

Only 13 hours later he is out in the cold rain on an artificial-turf field working on No. 300 with his trainer, Brian McNamee, and his buddy and training partner, Ken Jowdy. Sherpas are slackers compared with Clemens between starts, when he grinds through what he calls his Navy SEALs workouts. ("The easiest day I have," he says, "is the day I pitch.") They begin with this "recovery day," he says, when he "flushes" from his body any poststart soreness, typically in his pitching shoulder, lower back, hamstrings and calves.

Over the next hour, with his pitching hand still swollen and bandaged, Clemens zips through a se-ries of exercises that includes 130 abdominal crunches, runs totaling 1 1/2 miles at a 6:40 pace, several sets of jumps with a four-pound jump rope, several football-style agility drills, ball-pickup drills and basketball-style line drills.

From the field Clemens briskly walks four blocks to a gym where he spends another hour doing rack-rattling lower-body weight training, such as squats and leg curls, and more cardio work on some combination of the treadmill, stationary bike and elliptical trainer. There is a reason why almost none of the moms or lobster-shift gym members gawk at the only six-time Cy Young Award winner in their midst: He is here almost every day. "I'm gonna break this thing!" Clemens says, straining atop the stationary bike. He's already broken one bike, and there is a glint in his eye as this one begins to emit the mechanical warning gasps of surrender. "Hear it? You hear it?" he says. "I'm gonna break it!"

The bike lives another day, which may not be true for Jowdy's confidence on the golf course. Working out is a social activity for Clemens. He craves partners, most of whom can't keep up with him or his needling, so he's devised a sort of rotation to keep him company. Fellow Yankees pitcher Andy Pettitte is one partner.

Former teammate Ted Lilly enlisted once but lost his lunch about halfway through the cardio portion. "I ate two sandwiches before I went out with Roger," said Lilly, now with the Oakland A's. "One stayed down. One didn't."

Today Clemens is calling Jowdy "Van de Velde," in honor of their golf match three days earlier. On the par-5 18th hole Jowdy was in the fairway in two, needing only a bogey to win. He took an 8.

"Hey, Van de Velde, you know how people get a brain freeze from a Slurpee?" says Clemens, who plays to a six handicap. "You looked like you had a head freeze in the car coming back. Wow, I thought you were goin' down. I was fixin' to hit the OnStar to get you some emergency help."

Clemens is especially excited today because, with 299 in hand, it is the first day he can concentrate on 300. His wife, Debbie, and four boys--Koby, Kory, Kacy and Kody--are flying in the next day.

His mother, Bess, who has emphysema and is recovering from a recent bout of pneumonia, will follow on the weekend. Fifty or so former teammates and friends will also be arriving.

No matter what his victory total, however, Clemens never acts his age. He is the high school jock who, $100 million later, still doesn't call anybody by his given name--Yankees shortstop Derek Jeter is "Jeet," catcher Jorge Posada is "Georgie," manager Joe

Torre is "Skip" and Jim Murray, one of Clemens's agents, is "Taco Neck," after his habitual head-tilt to cradle his cellphone while writing notes, which resembles the universal taco-eating position.

His pitches have nicknames too. Clemens throws, for instance, a "splittie" (splitter), a "Hook 'em, Horns" (curveball) and a "Racer X" (a fastball that rides back on the inside corner against lefties) but tries to avoid the dreaded "cement mixer" (a slider that spins too slowly). Even his truck has a nickname: Mean Machine. Befitting his outsized image, Clemens drives a Hummer H2. "The Mean Machine's great," he says from behind the wheel while mounting an offensive on Second Avenue. "People get out of your way."

Clemens drops off Jowdy at a diner and tells him to order Clemens's usual lunch while he parks the Mean Machine. Not long after Clemens sits down, he is served his Rocket fuel: a platter with a breast of chicken and a bacon cheeseburger nearly the size of a Manhattan studio apartment.

Somehow the conversation gets around to a hearing in the baseball commissioner's office over Clemens's famous ejection by umpire Terry Cooney in the 1990 American League Championship Series. Clemens remembers that all parties were carefully editing their recollections of the on-field language until commissioner Fay Vincent finally implored them not to, saying, "We're all grown men here."

"The stenographer was a little lady straight out of Little House on the Prairie," Clemens says. "She couldn't believe what she heard after that. The poor old woman's hands were shaking. I'm thinking, I hope Little House on the Prairie makes it."

His recovery-day work isn't done yet. Clemens works out again after he arrives at the ballpark at 3:30 p.m., usually strapping weights on his ankles for exercises designed to maintain strength in his groin area.

Day Two begins back on the artificial-turf field, as early as 7 a.m. The conditioning drills closely mirror those of Day One. At the gym Clemens substitutes upper-body weight work for the previous day's lower-body weight work. He moves through 12 different curls, lifts and pull-downs. "People who don't know get put off by lifting," Clemens says, "but I never lift more than 25 pounds above my head."

He follows the weight work with another 20 minutes of cardio on the treadmill and bike. Then he works out again at the stadium. He does a series of light-weight exercises for strength and flexibility in his pitching shoulder. He also throws for 12 minutes in the bullpen, using all his pitches: four-seam and two-seam fastballs, slider, curve and splitter.

On Day Three, Clemens runs through another full morning of crunches, agility drills and cardio, though his weight work is scaled back to a few exercises at the ballpark. He throws again in the bullpen, though this time he moves Borzello up to 55 feet, not the standard 60 feet, six inches. For this, too, he has a nickname: Williamsport. "I'm not looking for full extension," he says. "I just want to concentrate on staying on top of the ball, keeping my hand behind it. It helps you repeat your delivery."

When Clemens is satisfied with the muscle memory in his body, and especially his right hand, he tells pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre, "That's it." It's like tuning a piano. One day last month Clemens threw only 12 pitches before stopping his Williamsport.

Day Four, the day before he pitches, is a light day. Clemens plays catch in the outfield. He might jog lightly in the outfield if his body is sluggish. He may do light weight work for his shoulders. The hard part comes that night. "I don't sleep sound," he says of the eve of his starts. "I'll take Tylenol PM or something, and it doesn't help. I don't care if it's the seventh game of the World Series or a Sunday game in May--you don't sleep sound if you care about your work, because you have a lot of things going through your mind. I can relax [on Day Three]. That's my night to rest soundly.

"It's like when you're anxious before [pitching] a game in high school. You've got to take the rubber and control the frame. You're going to be the hero or the dog. You can't afford to have a bad performance."

Game day. This is what the sweat equity of the past days has been about. Monday marked Clemens's 584th start in the majors, and it did not give him his 300th win. He has fewer than two dozen starts left. There is no place for nicknames and levity now.

"Roger is a great teammate," Yankees first baseman Jason Giambi says, "but on the mound? He's one badass mother."

In the first inning of Game 4 of the 2000 ALCS, in Seattle, Clemens buzzed a fastball near the whiskers of Alex Rodriguez. And then he did it again. Rodriguez wheeled and yelled at Clemens, "Throw the ball over the f------plate!"

"I never heard him say anything," Clemens says.

Seattle manager Lou Piniella was furious. Rodriguez's mother later complained that Clemens was trying to hurt her baby.

"Another big misconception," Clemens says, shaking his head. "They don't understand: When you face a hitter and you're trying to get him off the plate, you throw at his hands. Say, like A-Rod. I'm trying to get a ball at his hands."

Clemens typically takes aim at a piece of his catcher: the mitt mostly but sometimes a shoulder or a knee. To get a pitch under the hands of a hitter he must aim toward the empty space between the catcher and the hitter. "So you're visualizing throwing in that open area," Clemens says of the brushback pitch. "And if you let that ball go off the fingertips one or two inches in the wrong spot, it's going to be up and in, heads-up, all that stuff. But I'm not going to miss over [the plate]. Because I've done that before. And with [Greg] Luzinski and [Dave] Kingman and those monsters, that's gone. I learned that when I was 21."

Says Rodriguez, "I knew he was trying to set a tone." Clemens threw a one-hitter that day against Seattle, striking out 15 batters. A few days later he sent Rodriguez's mother one of the gift baskets the Yankees' wives had given the Mariners' wives. "I really wasn't trying to hurt her baby," he says.

"Best game I've seen in my life," Rodriguez says. "I've probably watched on TV and played in 5,000 games, and it's easily the best I've ever seen. His 140th pitch in the ninth inning was 98 miles an hour. His splitter was 95 and nasty.

"Roger Clemens is a role model for me. He is where I want to be: the financial rewards, the family happiness, the Hall of Fame career, the work ethic. He climbed the mountain, and he's stayed there."

Tony Gwynn liked to distill his hitting style to one word: carving. That was his expression for al-lowing the ball to get deep into the hitting zone and then slicing it through "the 5.5 hole," between the third baseman and shortstop. For Clemens, the operative word is downhill.

"Perfect," he says. "I work downhill. Stay tall. Stay back. Work downhill." In his windup he does a deliberate two-step: a drop step with his left foot and a step in front of the slab with his right. He can no longer see the catcher as his chin drops--he is soft-focused on the third base side of the mound--but he visualizes the target. "When I try to pick up the target too early, my chin drifts," he says. "That causes the [left] shoulder to fly open. You pick up the target as you're going home."

The mound never seems so damn high as when Clemens is erect over the rubber with his left knee up, the ball still in his right hand inside his glove. Imagine the last ominous click you hear from the chain drive of a roller coaster as it crests that first hill. At that moment the maximum amount of energy is stored. What comes next is pure downhill fury. "I'm six-four, so I have leverage," Clemens says. "Use your leverage and reach out there and get somebody."

Down, down, down the slope of the hill he roars, the stored energy released in an explosion of 237 pounds of power while he keeps his huge, meaty right hand behind the ball, his fingers on top--not on the sides--and his arm extended toward the target.

Nothing is wasted. The speeding coaster stays straight on its rails.

"Roger is massive across the back and shoulders," Stottlemyre says, "but much of his power comes through his great lower-body strength and pushing off properly." This is why he invests four days of sweat in every start, a program he tapers after the All-Star break to stay strong for the rest of the season. He is, body and soul, a power pitcher."

"I know why I'm able to keep my fastball at the pace it is right now: It's because of the work that I do," he says. "If I was a control freak as far as location and movement go, I could ride a stationary bike and do a little whirlpool and stretch and probably be fine. I wouldn't have to worry about getting sore. For me to do this it's a four-or five-day recovery time."

He weighed 212 pounds when he made his big league debut in 1984.

In '88, after "melting at the 200-inning mark in August," he says, he decided to reinforce his founda-tion. "I put almost two inches on my legs and booty," he says. He has trained fanatically over the years, though in different ways. With the Red Sox, for instance, he ripped off four-or five-mile runs two or three times so often between starts, he says, that "I knew every crack in the path along the Charles River." When he left Boston for the Toronto Blue Jays after the 1996 season--with Red Sox G.M. Dan

Duquette famously writing him off as being in the "twilight" of his career--he met McNamee, who tweaked his workout. In seven years, McNamee recalls, Clemens has showed up late for only one workout and missed none. "I'm glad I still enjoy running and doing the stuff I do," he says. "It's not work. I enjoy it because I know it gives me results."

There is more to it than that, which is apparent when he is told that Rodriguez wants to know what drives him. "A-Rod doesn't have to look any farther than to his left and his right," Clemens says. "He has a kid at second to his left and a kid at third to his right, and he's setting the perfect example for them: that you don't just come in and pick up your paycheck every 15 days. It takes a lot of work. I'm doing it because ... I want Andy [Pettitte] to know."

He is packing his bags. His three-bedroom Manhattan apartment seems bare when you consider that it's been his in-season residence for three years. A framed picture of Clemens with Cal Ripken Jr. by the Babe Ruth monument at Yankee Stadium does not hang on a wall but leans against a window on the sill. A few boxes are scattered about. "I'm sending stuff home now," he says.

"It's getting emptier because I don't want it to be the end of October, hopefully, and then a big transition."

Two years ago Debbie figured that when Roger won his 300th, he'd find another pitcher or record to chase down. This winter, though, a certainty settled over him like the warmth of the spring sun. This would be his last season. "They're ready for me to come home," he says, "and I'm ready."

He found in that decision--a twilight of his own choosing--tremendous peace and comfort. Never has he been more playful, never has he so enjoyed the brotherhood of baseball. One day he's telling teammate Mike Mussina, whose flesh tone may actually be deepening beyond its usual pallor, to up his SPF factor. Another day he's yelling to a smiling Pettitte, "First time I've seen your teeth in a month. I was ready to hang a cryin' towel in your locker." He is allowing a crew from MLB Productions to film him behind the scenes this season for a sort of video scrapbook, including a planned trip next week to his father's grave in Ohio. "The neatest thing about shutting it down this year," Clemens says, "is that more guys, even from other teams, are coming up to me to ask questions before I go."

"Roger, from Day One of spring training, has never had a down day," says Stottlemyre. "You see a little extra spark every day at the ballpark. It's almost like, 'I know this is my last go-round.' He's always had a lot of energy. This year he's stepped it up." Iduna, the Norse goddess of youth and beauty, also kept a box close by. Hers was filled with golden apples.

Whenever the gods felt old age creeping up on them, Iduna opened the box--Clack-clack!--and gave them a golden apple. They took a bite and were filled with the magic of youth.

Inside his hard case, Clemens keeps the tools and totems of his craft. His steel protective cup. Old game balls. His game hats. A nameplate from his spring training locker in 2001, on which former teammate Allen Watson wrote that Clemens would go 22-6 and win the Cy Young. (Clemens went 20-3 and won the Cy.) Four game-ready black fielding gloves. Four mouthpieces in a lime-green plastic case.

"I bite down when I pitch," Clemens says. "My jaws and temples used to be real sore after games. I used a football mouthpiece until my dentist said, 'I can make you a thinner one that's more durable.' I go through about four a year."

And then there's a Men in Black visor. "It's the Men in Black case," Clemens says, finally explaining the stenciled acronym (if not the E-22, which, it turns out, is the equipment manager's code for Clemens's gear). "I got the visor at Universal Studios."

Torre says, "Roger takes me back to what Roy Campanella said: 'You have to have a lot of little boy in you to play this game.'"

There are no golden apples inside Clemens's case, so he labors lovingly at keeping the ravages of age at bay. The work allows him to stand tall on the mound and reach back to his youth for a young man's fastball. The baseball will resonate like a sweet memory in the mitt of Borzello. The two of them have a running gag about it. Borzello will shake his head over the quality of Clemens's stuff, the stuff that cannot be bequeathed, and Clemens will bark, "What are you shakin' your head about?"

"I've already told you," Borzello will say.

And at that moment of affirmation Clemens feels serene in the knowledge that all this work has brought him to the brink of 300 and will soon bring him home to his family, with almost no compromise. That is what's inside.