Weekly Countdown

Also in this column:• Why Doc leads Coach of the Year race• The NBA vs. the European game

MILAN, Italy --

5. The meeting. The lobby of the Quark Hotel on the south side of Milan was overwhelmed with stylish blazers, wavy hair and exasperated Italians speaking with quiet urgency into the cell phones pressed to their ears. Thursday was the deadline day for transfers in the Italian football Serie A -- among the world's most powerful soccer leagues -- and the team presidents and general managers, as well as the agents and players themselves together with the TV crews, Web site producers and radio and print reporters, were milling around and bumping into each other like caffeinated atoms.

Standing in the back of the lobby, dangling a pair of orange-trimmed sneakers from his long fingers and talking via cell phone to his mother, was Nicolas Batum, the 6-foot-8 French forward who expects to be playing in the NBA next year. After he hangs up his phone, we drink in the menagerie of self-importance alongside Arnaud Leproux, media director of the French club Le Mans Sarthe, for whom Batum will star in a Euroleague game tonight.

Leproux stares blankly at the vast navy-blazered sea of power brokers and says, "In the beginning they come in, and they are all hugging and kissing to greet each other. But now'' -- and here Leproux extends his hands before him in forceful demonstration -- "now you can see them saying to each other, 'No, you cannot do this to me!'

"Then you can see downstairs there are many couches arranged for them to have more private meetings and negotiations between the teams and the agents. And if they are serious, then each team has a private space or office where they can finish the deal.''

It is not unlike dynamics of the Red Light District in Amsterdam, I offer. "But here's the thing,'' I say, thumbing at the 19-year-old Batum standing next to me. "This guy has a chance to make more money in the NBA than any of the football players here. Here he is and they have no clue about his value.''

"Maybe in the future, yes,'' Leproux says. "But right now, I think there is more money here.''

4. We go downstairs. For the interview, we walk down a spiraling case of stairs around and under a modern chandelier arranged like long organ pipes made from three dozen tubes of lighted glass. The teal couches are occupied by the soccer executives and agents engaging in the foreplay of their pillow talk. One of the conference rooms has been rented by Euroleague TV, whose interviewer directs Batum to sit in a chair in front of the league's official backdrop displaying the logos of its commercial sponsors. It is a low-budget operation, and the pale fluorescent light overhead emphasizes the shadows under Batum's brow and his day-old beard. The poor lighting makes him look thin and tired.

"I want to be in the NBA next year,'' Batum tells me a few minutes later. He says he will definitely enter the draft in June, when he and Danilo Gallinari of Milan promise to be the first two international players chosen.

For Batum, the choice is simple: He could have joined the NBA last year but chose to wait; he doesn't plan to wait an additional year.

But the leaders of his French team are in a more nuanced predicament: acknowledging on the one hand that the best talents must seek the highest level of play, and yet wanting Batum to remain in Europe until he is a bigger star, to their benefit as well as his own.

"All of the team and all of the players wish the best for Nicolas to go to the draft and the NBA,'' Le Mans team president Jean-Pierre Goisbault says. "But personally, we don't want him to go to the NBA and stay on the bench like a lot of French players do right now. He has so much talent that it is better for him to stay one more year in Europe, to really dominate in Europe, and then to have a good role when he goes into the NBA. The situation that we know right now is that these players who are able to play basketball, they stay on the bench in the NBA and play two minutes in the garbage time and it's a disaster. We don't want it to be that Nicolas will do that.''

3. The father's lesson. His father, Henry Batum, was a professional player in France for 10 years. "He died on the court when I was 2 years old,'' Nicolas says. Henry Batum was at the free-throw line when he suffered a massive heart attack.

Unlike his son, he was a thickly built player, a 6-7 rebounder who played under the basket. "Me, I am a wing, so we have not the same game,'' Batum says. "I think he is watching me.

"I try to finish what he begins. I play basketball also for him. If he is there, I think his wildest dream is to watch me go in the NBA. So I try to make that for him.''

His mother, a nanny, raised Batum and his sister, who was two months old when their father died. "My mother is very, very important in my life,'' he says. "I think if I go to the NBA, she will follow me next year with my sister. Every time I make a good game, she is there. She is telling me, 'You are good, you will be good next year.' She is trying to keep me comfortable, to just think about basketball. Don't think of the girls, the agent, the money. Just think basketball.''

2. The Hoop Summit. Last April, in an All-Star game in Memphis between U.S. high school players and World Select team of young professionals, Batum exploded for 23 points (on 9-of-13 shooting from the field) with a trio of three-pointers, several skyscraping dunks and four steals. "One week before I was in the Hoop Summit, nobody knows me,'' he says, laughing. "And one week after, my phone rings every time. I was very surprised.

"But now I understand everything. I try to listen to good people to help me -- my agent [Bouna Ndiaye], my mother. So now it's cool for me and I want to be in the NBA next year.''

Per the routine, Batum is playing two concurrent seasons in Europe. In the French league, he ranks as one of the top players while averaging 12.8 points and 4.9 rebounds in 28.9 minutes for Le Mans. In the more challenging Euroleague, however, he has averaged 8.3 points, 3.2 rebounds and 2.7 assists in 26 minutes. Batum has been the uncertain leader of one of the league's youngest teams; a good game is followed by a bad night, and up and down he goes.

"We must give him time,'' says his coach, Vincent Collet. "He is really young. Two years ago he was 17, but he was not really 17 -- he was much younger than this. Now he is 19 and there has been a lot of improvement with his consistency. The most important thing for him is to improve more mentally than in his basketball, because he has been given many tools to be great. But sometimes I have to remind him.''

Batum's perimeter shooting is still at issue, and some scouts believe the unreliability of his jump shot may hurt him in the draft. But Batum maintains that he doesn't worry about where he is picked. "The most important thing is to go to the NBA,'' he says. "It don't matter the team. So if I am No. 1 or No. 10, it don't matter.''

And if it turns out that he moved to the NBA too early? Europeans who are buried on the bench, he says, should be willing to return home to renew their careers. "Boris Diaw plays, [Tony] Parker plays, maybe [the Lakers' Ronny] Turiaf plays a little bit,'' says Batum, referring to his fellow Frenchmen. "The other [French] players didn't play. So it would be better for them to go back to Europe and play in the Euroleague with clubs like Barcelona or Panathinaikos.''

But that would mean accepting less money, I warn him. "I say it every time: Basketball is not my job; it's my passion," he says.

1. The consensus. There is no consensus. More than a dozen NBA scouts are in Milan, and they appear to make up 10 percent of the audience. Both teams are out of contention in the Euroleague, and Gallinari, the 19-year-old star of Milan who is expected to compete with Batum for the top European pick of the draft, is sidelined by a strained knee.

"We all came to see the top two guys go at each other,'' an NBA scout says.

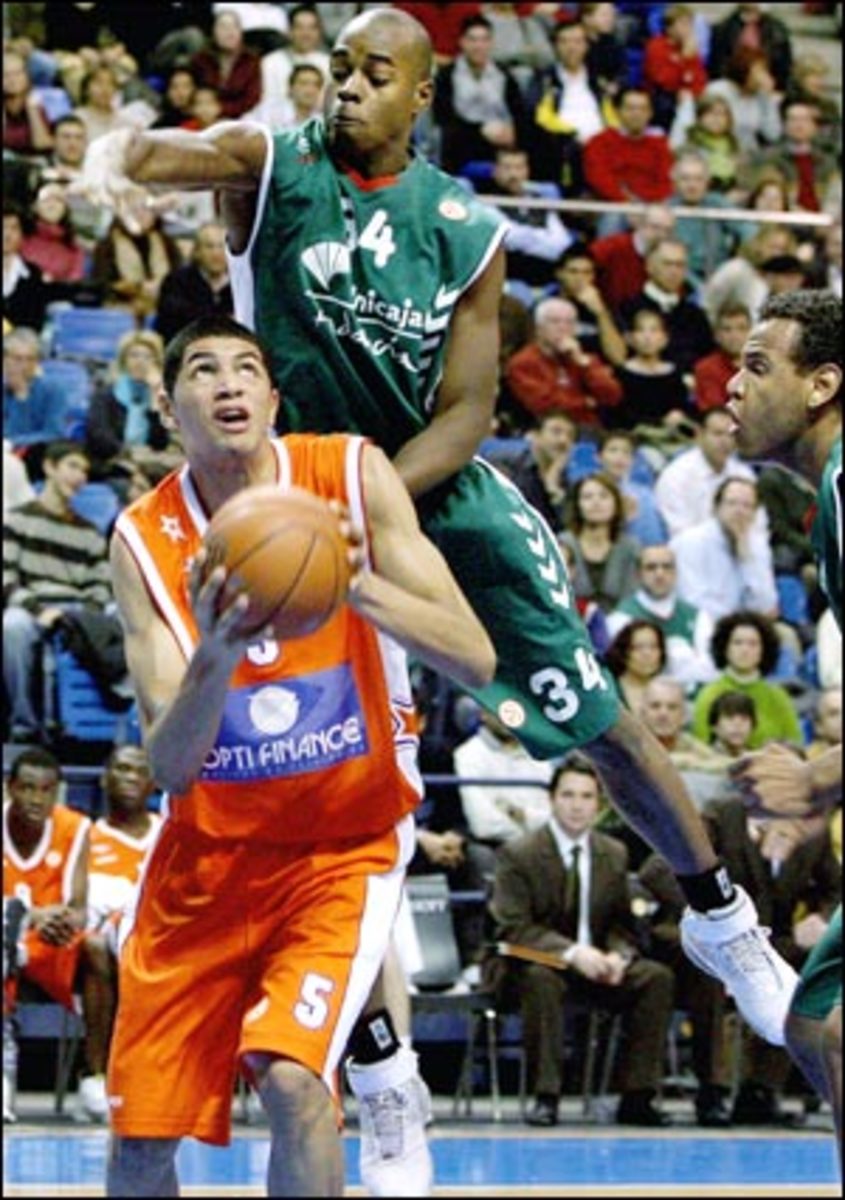

They focus on Batum instead. They watch Collet bench him after a disinterested beginning, then watch as he works himself into the game for 12 points (3-of-9 shooting), seven rebounds, four turnovers and three assists.

"He should have been in the draft last year, when he would have been a lottery pick,'' one international scout says. "Now I don't know where he'll end up. This is the sixth time I've watched him this year, and I have not seen him have a really good game yet. I know he's got it in him; I just haven't seen it.

"He should be making a big difference in the game, but he doesn't. He could be a hell of a player, but he's so passive. Every once in a while he'll do something, but then he disappears.''

But there are other perspectives. Over a stretch early in the second half, Batum makes a brief difference with a jumper, then a three-pointer, then a blocked shot to set up a teammate's three in transition as Le Mans opens up a 56-37 lead. They win 83-63 to finish 4-10 in the Euroleague, which will proceed to its second round without them.

"He has the ability to be an all-league defender after a couple of years,'' another scout says. "He has the wingspan of a pterodactyl, and even when he looks like he's loping, he's moving past other guys and just gobbling up space. He's going to be one of the top five athletes in the draft.

"There are times when he makes jump shots that he looks like a young Grant Hill. I don't know if he'll ever be a great scorer. He's a pretty good passer and not a bad ball-handler for his age, but he is a bit tender -- not a fiery kind of kid. He's one of the top seven or eight guys in the draft.''

And if he were to stay in Europe for another year? "His agent is known for doing the unexpected, for making a deal with a team to put his guys into the draft early,'' the scout says. "Why hold him back? Then teams will spend more time looking for more holes in his game. He should come out this year.''

And so he will.

4. How do you not put Nate McMillan on top for Coach of the Year? As a Celtics fan I'd love to see Doc win it, but even though it's the biggest turnaround for a team this season, that credit has to go more to Danny Ainge and to a lesser extent Kevin McHale. Meanwhile, McMillan, after losing the No. 1 pick in the draft, has taken the youngest team in the league and turned it into a playoff contender in the West. Keeping a young team confident is much more difficult than winning with KG, Paul Pierce, etc.-- Alex, Boston

Like you, I'm amazed by McMillan's success with his young team, but I disagree with your conclusion. Rivers' mission was more difficult. So far, he has been able to marry three stars who were used to neither sharing nor winning in recent years. The Celtics used to be a shallow, one-dimensional offensive team, but now they're leading the league in defense with Pierce and Ray Allen playing the best defense of their careers. Rivers is bringing out the winning qualities in Rajon Rondo as the second-year point guard of a veteran team, and he's doing it with no backup at the point (though that may change soon). A thin bench was expected to be another weakness that has yet to hurt the Celtics.

I'll have no complaints if the Blazers keep this up and McMillan wins the award, but my perspective is different from yours. McMillan entered the season with no expectations and therefore no pressure. Contrast that with Rivers, who looked like he was in a no-win situation: His recast team was expected to do well, and if it failed, then the blame would go to the coach. The Celtics needed a strong start more than any other team, but nobody expected them to be this good. Rivers has exceeded expectations.

3. Why is it that the Raptors are prepared to "strip Andrea Bargnani down to the core in order to rebuild him" into a center? Was this why they drafted him No. 1? Why does Sam Mitchell's handling of Bargnani look a lot like how he destroyed Rafael Araujo, starting before he was ready and then quickly sitting him, and in Bargnani's case, when he'd be better off at the 4 with Rasho Nesterovic (a true center) at the 5 and Chris Bosh at the 3?-- Tony Irwin, Burlington, Ontario

I wouldn't bring Araujo into your argument. He was "destroyed'' the moment the Raptors made the mistake of picking him No. 8 in the 2004 draft, turning his Toronto career into a mini-referendum on GM Rob Babcock.

You can't move Bosh to small forward to make life easier for someone like Bargnani. Bosh is the Raptors' best player, the foundation for everything they do. Not only would Toronto be messing with its strength, but a rash move like that also would send a bad message to the entire team by awarding the power forward minutes to Bargnani instead of making him earn them.

I don't have the impression that the Raptors want to rob Bargnani of his identity as a perimeter shooter. Instead, they want to supplement his skills with the ability to post up, exploit mismatches inside and become a versatile complement to Bosh. The question here is whether they need a big-man coach like Boston's Clifford Ray -- who recently helped Al Jefferson and previously worked with Dwight Howard in Orlando -- to learn the post-up moves to round out his game. Bargnani's recent slump is a natural part of his transition from a one-dimensional shooter to a complete player, but he needs to develop the inside game while he's young. The older the player, the harder it is to coax him into the paint.

3. Quite the lovefest you had there with Sam Mitchell. Are any coaches actually nice to reporters, or do they mostly treat you with veiled tolerance and short fuses? Who are among the best/worst? (Gotta love coach Sam's tailor, though. And the way his team is playing shows that his COTY award wasn't a fluke.)-- Keith Sutton, Winnipeg, Manitoba

I'd actually say that Mitchell is an excellent interview -- a bit difficult at first, obviously, but smart and entertaining as he warms up.

I've written about a lot of sports in more countries than I can remember visiting, and I tell friends that among all of the professional leagues, the NBA players are the best to deal with. That's probably because most of them have attended college and have learned how to carry themselves in diverse social settings, and also because well-spoken stars like Julius Erving and Michael Jordan have served as role models. Therefore, it's no surprise to me that the NBA coaches are even more accessible. I would rate more than half of them as excellent interviews, including Rivers, McMillan, Mike D'Antoni, George Karl, Byron Scott, P.J. Carlesimo, Jerry Sloan, Eddie Jordan ... with apologies to others who belong on the list, I think I've made the point.

Gregg Popovich can be difficult at times when TV cameras are around, but when those lights turn off, he becomes as smart and engaging as anyone I've ever met. That he is more comfortable with print reporters than with TV people is, to me, a compulsion of sheer brilliance and exquisite taste, and an example that everyone in sports should follow.

Some coaches severely limit their access to the press, such as Pat Riley and Isiah Thomas. Isiah is someone who makes a better impression in a one-on-one interview than when he is being interviewed by a pack of reporters. His press conferences are taking on a last-days-of-Rumsfeld look.

1. Will Grant Hill be able to have a major impact for the Suns in the postseason, or will he burn out before that?-- Paul of Menifee, Calif.

Does anyone have worse luck? Hill's recent bout of appendicitis sidelined him for two weeks. If he can regain his strength, his latest misfortune may serve to shorten his season -- and that may enable him to remain fresh throughout the playoffs, with his health playing a key role for the Suns.

3. More sincere fan support. After living in Europe for six years in the mid-1990s and covering a lot of European basketball in that time, I was shocked by the relative apathy of NBA buildings. NBA fans expect to be entertained. The Europeans have a different relationship with the game: They expect their team to win, and so they channel their energy to either demand victory or to complain about losses.

Fans in Europe don't need to be told when to cheer for their team by scoreboard "noise meters'' or Hollywood movie clips. They bring their own trumpets and bass drums and sing homemade songs in honor of their favorite players.

But let's be reasonable too. If NBA crowds seem to be dumbed down by comparison, it's because the NBA has marketed itself as less of a discriminating sport and more of a mainstream entertainment in order to sell more tickets. One thing European basketball needs is to sell more tickets.

The downside of intensive fan support is that the Europeans can get carried away. There's a reason that the team benches are protected by curved housings of Plexiglas that look like bus stops. In many countries, outraged fans will throw heated coins at players, light up flares (that sometimes ignite their own seats) and force riot teams of police to surround the court in their outfits of helmets and shields. I remember attending the equivalent of a Euroleague playoff game between the top two teams in Athens, and afterward the players from the losing team were warned against returning to their homes that night. The next day one of the players reported that his house had been stoned by unhappy fans.

The result is more pressure on the players to perform at the highest levels. As much as some NBA teams hate to lose, they don't feel anything like the pressure of the top teams in Europe.

2. Fewer timeouts. The NBA has more timeouts because it sells far more TV advertising, which is a crucial weakness for the European leagues. Nonetheless, the result is that the European game is played to a smoother flow, especially in the last two minutes. You don't see European coaches calling one timeout after another in crunch time. For an American spectator accustomed to drawn-out endings, the tension of a game in Europe builds naturally -- and concludes sharply.

1. More player skill. The Europeans who come to the NBA have superior fundamentals because they work at it. They have no choice. The best players sign with professional clubs as teenagers and practice twice a day until they enter the NBA. The system in Europe does not assure youngsters of playing time until they earn it, and the coaches in Europe have more authority over their players than do the coaches in college or the NBA.

Americans train less with their college teams because of NCAA rules limiting practice hours in hope of providing student-athletes with time for their studies. That rule is a noble though half-hearted attempt at emphasizing the priority of academics, and it's issues like those that make our system more complicated than the straightforward basketball structure of the European clubs. Another issue in the United States is the role of AAU and other summer basketball programs, in which the younger players play in games rather than practice as the Europeans do. The AAU programs have enhanced the advantages of the Europeans in training their players in the fundamentals.

2. A unified professional league. Basketball is a minor-league spectator sport in Europe, compared to soccer, because basketball earns so little commercial investment. The Euroleague (as well as the national basketball league in each European country) is a niche entertainment, much like soccer in the United States

If the top clubs were to form an exclusive European league in which they only played each other -- essentially an NBA of Europe -- then perhaps they could draw international sponsorship.

The problem is that the idea is too late. All of the best European players have fled overseas to the money and prestige of the NBA.

So now European basketball must find a profitable model that isn't based on having the best European players. The NCAA has succeeded in doing this around the huge success of its March Madness tournament. Likewise must European basketball come up with a formula that suits its best interests, but it won't be easy given the old-world Olympic-styled politics that continue to haunt the sport.

1. Superior refereeing. American fans may laugh at this, as much as they complain about the officiating in the NBA. But to experience true sporting frustration, try being a basketball fan in Europe, where in many countries the crowds are convinced that their referees have been bribed. Rumors of referees taking money are commonplace throughout much of European basketball.

The issue goes back to the days -- as recently as the 1990s -- when the home team was held responsible for the "hospitality'' of the referees. There wasn't money to cover the costs of the officials, so the home team was expected to take care of their needs. As a result, many European clubs would take the referees out to dinner the night before the game, in addition to providing them with a complimentary gift (which, believe it or not, was entitled within the FIBA rules). I remember a player telling me that he happened to see the closet where his European club kept its store of gifts to be provided to referees -- it was stacked with expensive watches, pens and jewelry.

When it comes to impartiality and not playing favorites, the NBA referees are the ideal. No other basketball country comes close.

Note the crucial difference between fixing games in the NBA and Europe. Former NBA referee Tim Donaghy was working illegally with criminals who were trying to make money from betting on the games. In Europe, the fixers don't fix games in order to bet on them or profit by them; they fix the game simply because they want their club to win.

1. Omer Asik, a center for Fenerbahce Ulker of Turkey. One NBA scout predicts that the 21-year-old Asik will climb into the first round.

"He keeps having good games,'' the scout says. "He's a true 6-11, he's long and lean and he has a good sense of timing for rebounds and blocking shots. He's skinny and needs to get stronger, but he has the kind of body that can bulk up.

"At the start of the year, he was on nobody's list. But he has been having good performances.''

Asik had nine rebounds and two blocks in a recent Euroleague game at Panathinaikos. Overall, he is averaging 6.5 points, 5.0 rebounds and 1.3 blocks in 18 minutes per Euroleague game.

"His style of play is a little bit like Horace Grant,'' the scout says. "He's an inside player -- he plays the sides of the lane from the free-throw line down. He has some good moves, he's a good jumper and he has a nose for the ball. Most important is that he has the means to keep improving. He will be a good value for a team picking near the end of the first round.''