On the road to recovery

What price, clean sport?

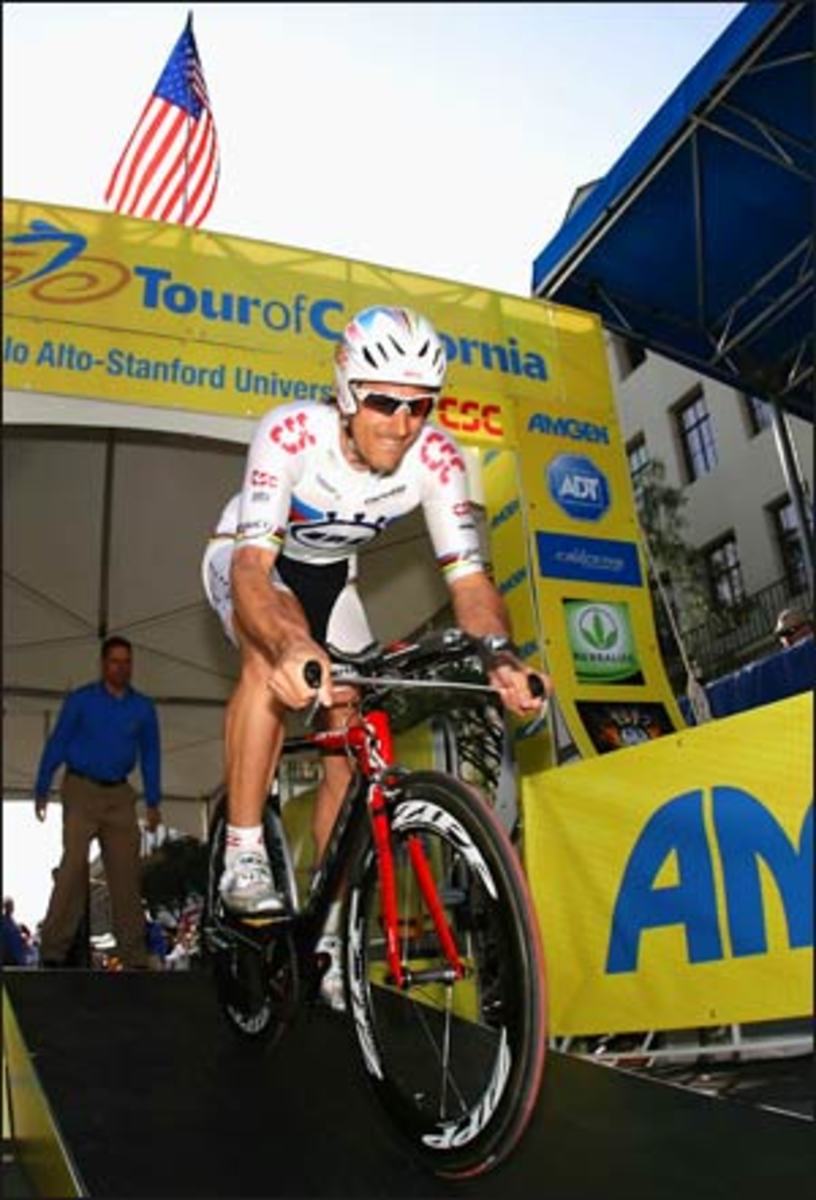

Ask Fabian Cancellara, the reigning world time-trial champion who destroyed the field in Sunday's Tour of California prologue -- a 3.3 km. appetizer for the seven stages to follow.

Rocketing from this city's tony downtown onto the Stanford campus, the Swiss rider finished in 3:51, more than four seconds ahead of the runner-up. On such an abbreviated course, that qualified as a Secretariat-caliber blowout. .

Cancellara's dominance came despite a rude interruption the night before. Ten minutes into his massage at the team hotel, there was a knock on the door. Some drug testers had a plastic cup with his name on it. "That means my massage is over," recalled Cancellara. "But that's the rules. For me, I don't care. I do my job, I do my best."

Cancellara is but a single star in a constellation at this race. Sponsored by pharmaceutical colossus Amgen, the third edition of the Tour of Cali boasts the most formidable collection of cycling talent ever to compete on American soil.

The seven world champions making their way south to the finish in Pasadena will include Italian strongman Paolo Bettini and Belgian uber-stud Tom Boonen, both of Quickstep. Further ratcheting up the star power was Rock Racing, which, for reasons soon to be made clear, lured Italian sprinter Mario Cipollini out of retirement to don its skull-emblazoned jersey. For a man a month shy of his 41st birthday, a guy who hadn't raced for three years, the Lion King looked pretty good, finishing a respectable 44th.

The prologue could not begin quickly enough for race officials, chiefly because it deflected the focus from the riveting sideshow by Michael Ball. He's the mercurial owner of Rock Racing, a continental squad -- that is, a cut below the ProTour teams also racing here -- in its second year of existence. He's also a scrappy, combative ex-bike rider whose Las Vegas roots tend to show.

A half-hour before the prologue began, Ball was strutting like a generalissimo outside the team's enormous black coach, which was bracketed by Rock Racing's distinctive, if not exactly practical, or fuel-efficient, team cars: a small fleet of Escalades. With a quartet of models behind them, three Rock riders sat at a table signing team posters, chatting easily with fans who lined up five-deep to talk to them.

If those riders seemed especially relaxed for guys on the cusp of a week-long ordeal, that was because they'd been chucked out of the race a day earlier.

Some background: For this year's race, the Tour of California adopted, in its words, "the most comprehensive anti-doping protocol in cycling history." One of the strictures placed on the 17 teams: Each was required to guarantee that none of its members were the targets of any ongoing doping investigations.

That was a problem for Rock Racing. During the past offseason, Ball signed a trio of riders with sketchy pasts. Santiago Botero, Oscar Sevilla and Tyler Hamilton have all been linked to Operacion Puerto, the two-year-old doping scandal that has ensnared scores of pro riders. Although all three deny wrongdoing, and are currently licensed to ride by cycling's governing body (UCI), Tour of California officials made the call to exclude them from this event.

This led to Saturday's semi-surreal press conference, in which Ball -- clad in the form-fitting, Lycra kit sported by his riders, as if he were the manager of a baseball team -- figuratively manned the barricades, railing against The Man on behalf of exploited cyclists everywhere. Channeling Samuel Gompers, he urged the formation of a rider's union, and decried the sport's fixation with ... well, with identifying cheaters, and punishing them.

"The past is the past," he said. "We have a moment right now to change this sport. Let's move forward. If it means giving these guys amnesty, do it. Stop digging up graves."

It isn't just ghoulish, this obsession with punishing dopers, in Ball's view. It's bad business.

"This sport is going to wither on a vine and die," he warned. "Sponsors are bailing out. If things continue with these conditions, I can't do anything else but exit. It doesn't make any sense business-wise."

Rock Racing will try to get through this 650-mile race with five riders, while the other 16 teams started with eight. Today's stage starts in Sausalito and ends in Santa Rosa, the hometown of defending Tour of Cali champion Levi Leipheimer. Levi's been down in the dumps since it was announced last week that his new team, Astana, would be excluded from the Tour de France. A win on his home turf today will take a bit of the sting out of that awful news.

The peloton will arrive in Santa Rosa via my backyard, almost. Gliding along U.S. 1, past Stinson Beach and Olema -- epicenter of the 1906 earthquake that leveled San Francisco -- through Point Reyes Station (pity they can't stop for a scone at the Bovine Bakery), and along Tomales Bay. The riders will be plying the same rural byways on which I train. At roughly half the speed.

I'm happy to share these roads, just as I'm pleased with the direction in which this sport is going.

Dump on this sport all you want, but give it its due. Cycling is working hard to get clean. First-time offenders aren't suspended for 10 days, as was the case in baseball until 2006 (It's now 50 games). They're out for two years, minimum. As of '08, the UCI requires its members to obtain "biological passports" -- a series of tests that establish an athlete's baseline profile. This forensic approach makes it much easier to detect when a rider has, say, transfused his blood or micro-dosed with EPO.

Going against the grain, as his DNA apparently commands, is Ball, whose team's jerseys feature a skull wrapped in a crown of what appears to be barbed wire. What's up with that?

"These guys have been crucified in the media and by the governing bodies," he told me recently. "They're not martyrs, but they've been crucified. And it's just wrong, man. This whole idea that there now has to be a black cloud that follows them for the rest of their careers is asinine. I mean, it's just a sport. Those governing officials are eating their young."

Ball is correct, in the sense that there is a definite backlash in this sport right now, as cycling lurches to put its sordid past behind it. That's bad for Hamilton & Co. It's bad for Astana, which, despite an offseason makeover, will not ride in the Tour de France -- a clear case of many clean riders being punished for sins they didn't commit.

It's not necessarily bad for cycling