The Four Tops

Four seconds. That's all it took. Four seconds for UCLA freshman forward Kevin Love to bury Xavier for good after the Musketeers had mounted a comeback with an 11-2 run in the second half of last Saturday's West Regional final. Four seconds for Love to snatch the ball out of the net, take one step out-of-bounds -- his right foot planted, his left foot inches above the floor -- and snap an immaculate, 70-foot chest pass to teammate Russell Westbrook for a layup and a 14-point lead. Four seconds to crush Xavier with basketball's answer to a 60-yard touchdown throw. For one glorious, fleeting moment the old-school chest pass was as sexy as a Dwight Howard slam dunk. "I love hearing the oohs and aahs you get from the crowd," Love says, "because you rarely ever hear them for a pass. You usually just hear them for a dunk."

It was a remarkable pass by a special player in an unprecedented NCAA tournament, the first in which all four No. 1 seeds have advanced to the Final Four. But Love's once-in-a-generation outlets won't be the only singular skill on display this week in San Antonio, where the Bruins will join Kansas, Memphis and North Carolina in "as high quality a Final Four as there's ever been," says Jayhawks coach Bill Self. In a bracket with chalk deposits the size of the cliffs at Dover, each team features a star with an unconventional signature move that could unhinge an opponent this week, especially an unfamiliar one. (None of the Big Four faced each other this season.) In the end, each weapon could be decisive in close games between teams with remarkably similar (and rarefied) talent levels.

No Final Four in recent memory has showcased a more diverse bag of tricks. North Carolina junior forward Tyler Hansbrough has made a mockery of low-post fundamentals with his go-to move, an unorthodox (but highly effective) hybrid of a jump hook and a turnaround jumper that Tar Heels coach Roy Williams calls "the shot put." Kansas junior guard Mario Chalmers specializes in reading an opponent's eyes and springing into passing lanes for steals, an art he learned from his mother, Almarie, his YMCA coach during grade school in Anchorage. And Memphis junior swingman Chris Douglas-Roberts perfected his signature move, a herky-jerky midrange floater, on the asphalt courts of his native Detroit.

"Old-man tricks," Tigers point guard Derrick Rose calls the various ball handling maneuvers that Douglas-Roberts uses to penetrate the lane in Memphis's dribble-drive motion offense. "Earl the Pearl [Monroe] is my guy," says CDR, whose repertoire includes a freaky inside-outside dribble, a more traditional crossover and a series of unpredictable, hunched-over feints that Michigan State's Travis Walton, who tried in vain to guard him last week, called a "snake move."

"I just have an unorthodox kind of game, like everybody from Detroit has," says Douglas-Roberts, a first-team All-America whose 25 points helped Memphis torch Texas 85-67 in Sunday's South Regional final. "We like to create our own shot and take a lot of scoop shots and in-between shots." But once the 6' 7" Douglas-Roberts approaches the basket, his favorite move is clearly the running teardrop ("My floater is always in my back pocket," he says), which he can loft above the outstretched arms of taller defenders with either hand from the baseline, the middle of the lane and any other nook or cranny the defense provides. "He'll shoot it from 12 to 14 feet to where it's not a true teardrop floater, it's more of a push floater," says Tigers assistant coach John Robic. "But he's so confident in it, that's what he wants to shoot."

He'll need that chutzpah in Saturday's national semifinal against UCLA, especially if the Bruins decide to use the same quirky one-man zone (with a stationary big man clogging the lane) that worked to perfection the last time these two teams played, a 50-45 UCLA win in the 2006 West Regional final. Then again, neither the 37-1 Tigers nor Douglas-Roberts is the same as two years ago. One big difference: CDR's three-point shooting has risen from 31.0% two seasons ago to 41.6% this year. "Chris has a consistent [outside] shot now," says teammate Doneal Mack. "So if he sees you back off, he's hitting it."

By contrast, if UCLA's Love spies too many Tigers attacking the rim, he'll make them pay with his court-length passes, aesthetic wonders so simple and clean that they seem to come straight out of a glossy European design magazine. With apologies to Davidson's jump-shooting Stephen Curry and Western Kentucky's buzzer-beating Ty Rogers, the most awe-inspiring highlight of the 2008 NCAA tournament didn't even take place during a game. In a sequence caught by CBS cameras that's fast becoming a YouTube classic, Love stood behind the baseline practicing chest passes at the Honda Center in Anaheim the day before the Bruins' first-round game against Mississippi Valley State. Normally this would be about as exciting as listening to coach Ben Howland ruminate on the finer points of the defensive stance. But as Love released the ball with a flick of his wrists, it flew over the free throw line, over the half-court line, over the other free throw line, over the rim and down through the net.

Swish. The Bruins, who'd seen Love's 94-foot parlor trick before, turned away and chuckled. But first-time observers whooped in disbelief. It was no fluke, but rather the result of years of training. Growing up, Love did fingertip push-ups to strengthen his wrists, and by his sophomore year at Lake Oswego (Ore.) High he could fire chest passes from one basket to the other. "I'll tell you the play that got me," says Kerry Keating, who recruited Love to UCLA and is now the coach at Santa Clara. "During a high school game he took a made basket, got out-of-bounds and with his momentum going away from the court flicked a chest pass 75 feet. I looked at people in the gym and asked, 'Do you know how hard that is?' "

As soon as Bruins speedsters Josh Shipp and Westbrook see that Love has gathered a rebound, they bolt to the other end of the floor like wide receivers taking off on fly patterns. "All we have to do is run," says Shipp. "We know the ball is coming right on the money." If they're covered, Love can also fire a shorter pass to point guard Darren Collison for a more traditional fast break. And though UCLA scores only about two baskets per game off Love's booming outlets, the constant threat of one causes foes to change their strategy. If they send fewer players to the offensive glass in hopes of preventing Bruins run-outs, then they won't grab as many rebounds.

Truth be told, Love's outlets seem better suited for Carolina's go-go attack than for the slower tempo of UCLA's defense-first schemes, but after visiting both schools Love opted for Westwood. ("It was amazing playing pickup with him," recalls Tar Heels guard Bobby Frasor. "He was throwing [outlet passes], and you're just catching them in stride.") A Tar Heels front line of Love and Hansbrough might not have been fair, however, with the former controlling the defensive blocks and the latter owning the offensive end with his unique shot put move.

Indeed, Hansbrough looks positively Olympian when he catches the ball down low, turns to his left and -- instead of keeping his left shoulder closed, in the way of most jump-hook shooters -- opens his upper body and left arm toward the basket. Then, instead of releasing quickly from above his head, Hansbrough waits a beat before shooting from a lower point just behind his right ear. He might as well put chalk on his neck. "When I first saw it our freshman year," says teammate Danny Green, "I was like, 'What the hell is that?' "

The result may appear almost as unnatural as Hansbrough's on-court dance after he hit the game-winner against Virginia Tech in the ACC tournament, but there's a method to his quirky delivery. Psycho-T is so strong that he can ward off defenders with his left arm, sometimes bamboozling them by initiating contact, and he's big enough that he can avoid most blocked-shot attempts despite opening up to the basket. And the low release point? "That comes from him wanting to get fouled," says Tar Heels assistant coach Joe Holladay. "He can hold the ball longer, and he'll wait until he gets hit. He gets three points more often than most three-point shooters."

Hansbrough admits that he'll have to change his form once he moves to the NBA, the better to combat taller, more athletic defenders, and he has a tendency to force shots through double- and triple-teams because "he's so competitive, he wants to score over three guys," says Holladay. But at the college level, as Williams says, "he makes it so many times and it's so hard for people to get to it that we haven't done anything to change it." Despite the shot put connotation, it's still a soft shot with plenty of backspin, and Hansbrough relied on it to hit a game-winner at Virginia in February and two key baskets over Louisville's 6' 11" David Padgett in the Heels' 83-73 East Regional-final win last Saturday.

Besides, Hansbrough never has been much for style points, anyway. "If it's working, I'll stay with it regardless of how it looks," he says. "If I'm going to make a free throw by shooting it from between my legs each time, then I'd do that."

If Saturday's showdown between North Carolina and Kansas had a name, it would probably be the Roy Williams Existential Angst Invitational. Ol' Roy says he still has emotional scars from his famously tortured decision in 2003 to leave Kansas, the school he took to four Final Fours, for his alma mater, which he guided to his first NCAA title, in '05. But if everyone gets too wrapped up in a reverie over Williams's first game against Kansas since the Decision, the Jayhawks' Chalmers can snap them out of it in a flash with his uncanny knack for stepping into passing lanes for steals.

Chalmers led the Big 12 in swipes this season, averaging 2.43 per game, a year after setting the Kansas single-season record with 97. "Mario's off-the-ball instincts are as good as anybody's I've ever been around," says Self, who notes that the 6' 1" Chalmers is aided by large hands and an unusually long wingspan. But to hear Super Mario himself describe it, his signature skill is almost supernatural. "I try to read people's eyes," he says, "to see what they're looking at and read their minds." Then he springs into action, darting between a passer and his intended recipient, most often after slipping through a screen and anticipating a slow bounce pass or crosscourt pass.

Chalmers's father, Ronnie, is the Jayhawks' director of basketball operations, but both he and his son credit Mario's mother for his ball hawking binges. She knows the game, having played at Winston-Salem (N.C.) State and Methodist College in Fayetteville, N.C. "When I played in high school and in the Air Force, I was always a scorer, but [Almarie] was more of a defensive stopper," says Ronnie. "I say to my wife, 'You take credit for the defense, I'll take credit for the offense.' You always trust a woman's intuition. A lot of times my wife is thinking much further ahead."

But Chalmers's skill carries plenty of risks. The opposing point guards he'll face this week -- Carolina's Ty Lawson, and either UCLA's Darren Collison or Memphis's Rose if Kansas advances -- can punish him in the blink of an eye if he overreaches. "A lot of times if you make the steal, [it's a] momentum-changing play," says Self. "But it can get your big guys a foul, because a guard will gamble and miss, and then the other player drives the ball and the big guys have to come over and help." Not to worry, says Chalmers: He and fellow guard Russell Robinson "have a connection," so that one knows when to cover for the other if he oversteps his area of responsibility.

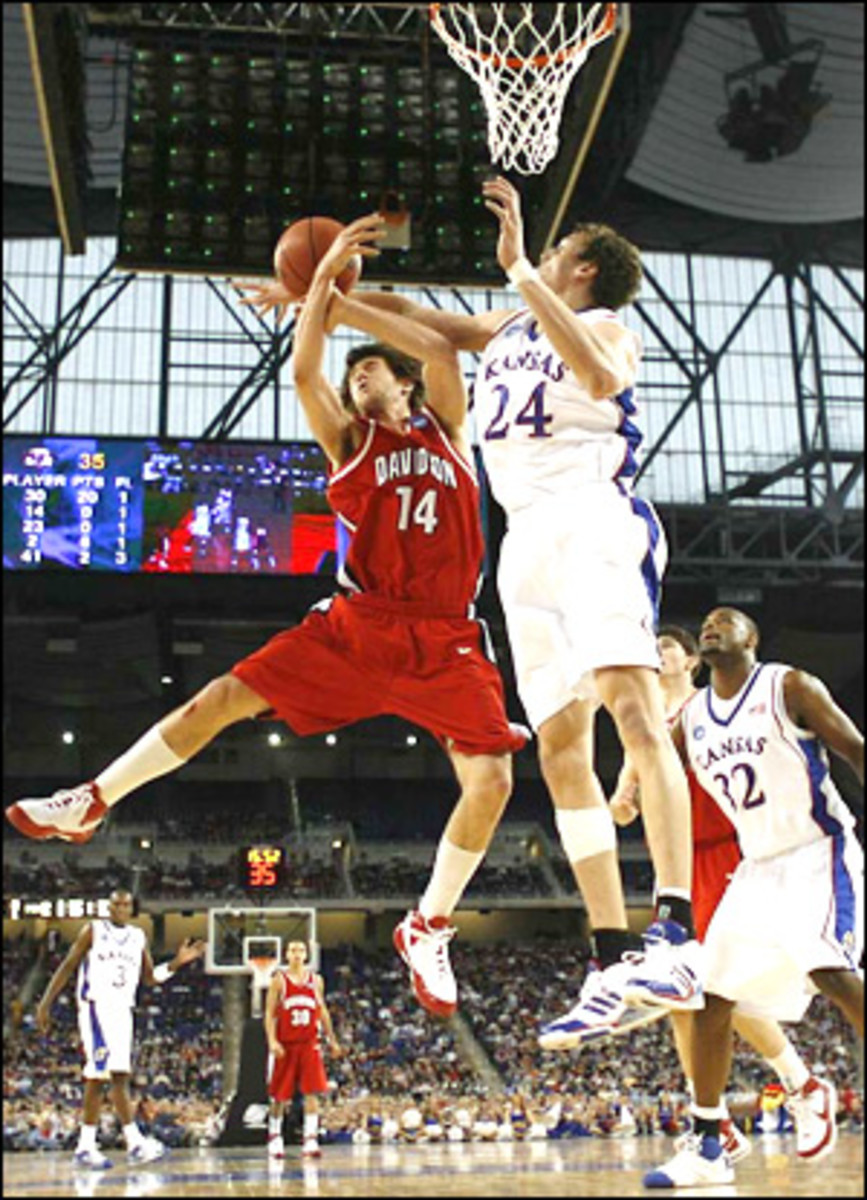

Yet for all the unique styles that will be on parade at this year's Final Four, it may help to recall that the heroes of NCAA tournaments past have often been called on to reveal new and unexpected talents in the crucible of the sport's biggest stage. In the tournament's first two weeks we have already seen potential for such enhancements. Hardly a skywalker, Love turned into a shot-blocking monster during UCLA's closest call, a second-round squeaker over Texas A&M, swatting seven in the second half. When Kansas was struggling to score against Davidson in Sunday's Midwest Regional final, Chalmers hit three first-half three-pointers. Likewise, Douglas-Roberts thumbed his nose at skeptics of Memphis's abysmal 60.7% free throw shooting by nailing 14 of 17 from the line on Sunday, part of a 30-for-36 team effort.

And Hansbrough? All he did was step out to drain four shots from between 16 and 18 feet against Louisville, a doomsday scenario for any Carolina foe. It was enough to make you wonder: Why does Psycho-T so rarely shoot a Psycho Three? "I don't know, man," says Hansbrough, who's 0 for 6 from long distance this season after going 3 for 8 during his first two years. "Threes just haven't fallen for me this year. Hopefully I'll knock one in sometime."

Who knows? It might just be on Monday night at the end of a Final Four for the ages.