In appreciation of Bud Selig

Here are two stories about Allan H. (Bud) Selig, one that you probably know, one that you may not. The funny thing is that they're really the same story, even if they happened about 60 years apart.

The first story goes back to the late 1940s, when Buddy Selig was in the sixth grade and he showed up with his team to play a neighborhood baseball game against his friend, Herb Kohl. As it turned out, Herb would later become a U.S. Senator for the state of Wisconsin. Buddy would become the commissioner of baseball. But that's trivia.

"Who is this guy?" Herb said as he pointed at a giant pitcher Bud brought to the game.

"What do you mean?" Bud said.

"I mean, who is this guy? I've never seen him before."

Bud looked annoyed. "Come on, he's just a kid from the neighborhood. My pitcher is sick. Come on, let's stop talking and play some baseball."

Years later, Bud still remembered that giant kid's name -- Jack Halser. And Jack went out and threw so hard that nobody on Herb Kohl's team ever even touched the baseball.

"We never even had a chance," Kohl said.

*****

The second story happened on Monday night, moments after rain and mud and howling winds forced Selig to make yet another historic decision -- to suspend a World Series game for the first time ever.

The game was suspended in the middle of the sixth inning, with Tampa Bay and Philadelphia tied 2-2. But the situation was almost very different. Philadelphia led the game 2-1 going into the sixth inning, just as the rain had turned the infield into a rodeo ring.

Members of the Philadelphia grounds crew rushed out and dumped bag after bag of Diamond Dry on the field, sort the way you might pull out a whole roll of paper towels to control a particularly nasty coffee spill. They managed to add more mud to the swamp and get the field just playable enough to allow Tampa Bay to score the tying run.

So, naturally, Bud Selig was asked what would have happened if Tampa Bay had not scored that tying run. According to baseball rules -- you know, the kind they have in rule books -- it would have been an official game. Would the game have been called and baseball's world championship given to Philadelphia in a shortened game?

"No sir, I wasn't going to let that happen," Bud said as he looked out over the huddled mass of sportswriters and broadcasters. And later: "It's my judgment ... it's not a way to end a World Series game."

The sportswriters looked at each other and shrugged. No, it was not a way to end a baseball game. But what exactly did he plan on doing about it?

Bud said: "The game would have been in a rain delay until weather conditions allowed us to continue; and that might have been 24 hours or 48 hours or who knows?"

An indefinite rain delay. Nobody had ever heard of such a thing. This was brand new, the Bud Doctrine, and the sportswriters wondered if the commissioner of baseball had the power to, you know, sequester an entire World Series for as long as necessary when there had not been one public statement made to the point beforehand.

Bud made it very clear: "I think I'm not only on solid ground, I'm on very solid ground."

Nobody even had a chance.

*****

Bud Selig was born to be a friend. That's why they called him Bud in the first place. When school teacher Marie Selig brought Allan Huber home from the hospital, the first thing she said to her older son Jerry was this: "We brought you a little buddy."

The name fit. Friendship would be his great skill; Bud always could get people to like him. He wanted to teach -- he got degrees in history and political science from the University of Wisconsin -- and even now you can see that he has the cliché mannerisms and absentmindedness of a history professor. He will often answer questions with lectures, and he will often bring up stories from long ago, and he will never hesitate to correct what he perceives to be a mistake.

Bud has another habit -- he calls people by their first names. That comes from another part of his life, the car-selling part. His father, Ben, and a partner had opened a car leasing company in Milwaukee back in '48, only the third auto leasing company in the United States. Ben asked his son to help out with the business for a while after college. Bud found that he was good at it. That's why critics, even now, will call him a "used car salesman," but that's unfair. Bud never liked cars all that much. It's just that people liked him.

Bud liked baseball. That's all. When he was a boy he would not talk about playing on a major league baseball team but, instead, owning one. He bought stock in the old Milwaukee Braves back in '63, when he was 29. He was furious when the Braves went South to Atlanta, and he led the charge to get the Seattle Pilots out of hock and bring them to Milwaukee. They were called the Brewers, just like the minor league team Bud grew up watching in town.

He loved being owner of the Milwaukee Brewers. He worked in a small office at the ballpark. Every day, at lunchtime, he got a hot dog smeared with ketchup and a Diet Coke from Gilles Frozen Custard. He got his hair cut at Tony Lococco's every Friday. He wandered through the press box more or less every game just to talk to the sportswriters, just to say how great Robin Yount looked or to ask why Mike Caldwell wasn't throwing too well. He had opinions, and he liked sharing them, and everybody liked him.

Then, later, he became baseball commissioner and that last part ended.

*****

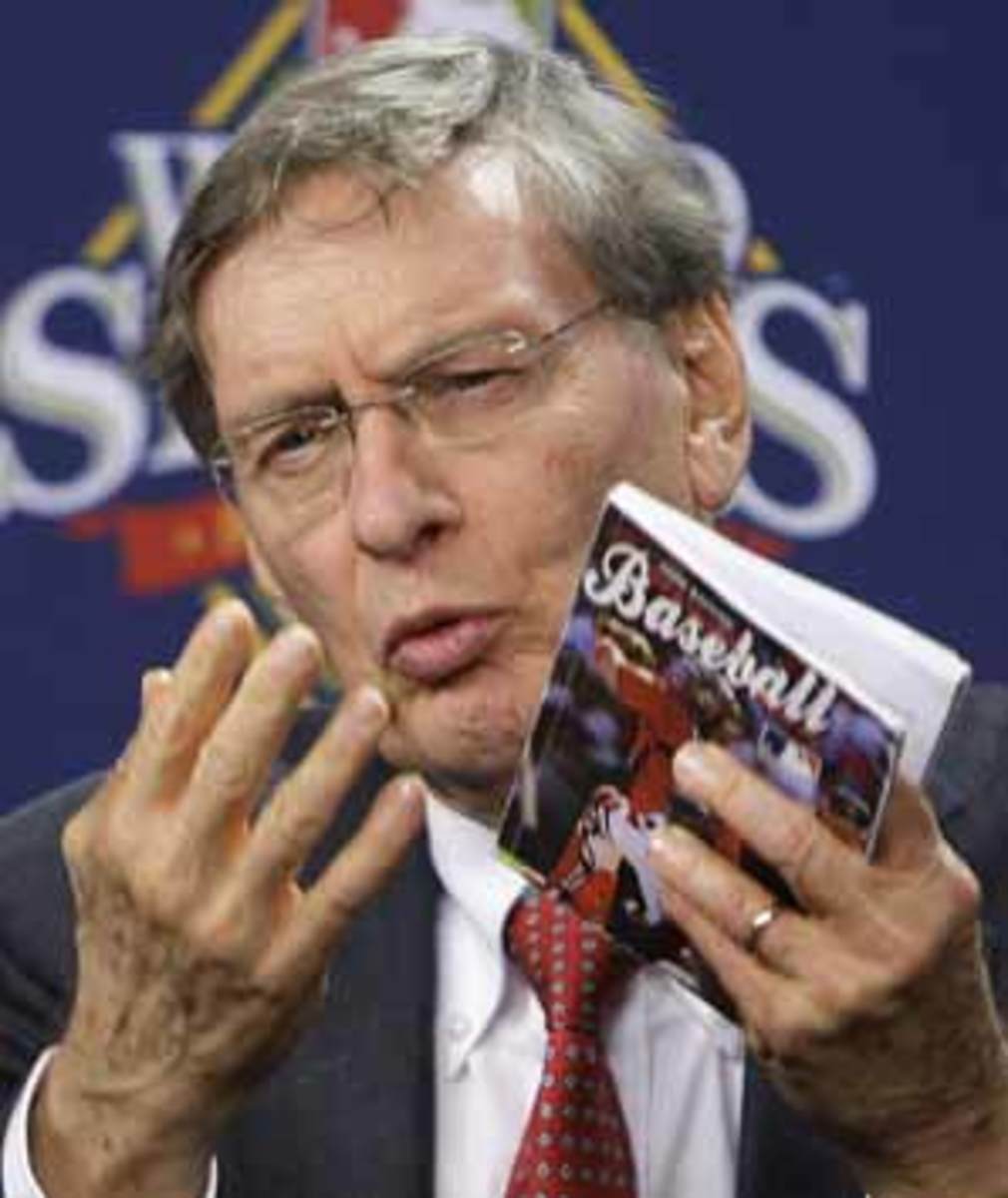

Bud Selig sat behind the microphone, and he had that look on his face, that beautiful and now familiar look of sheer befuddlement. He was trying to explain his odd atmospheric theory that just because the baseball season goes later into the year does not mean that the risk for bad weather is higher. Or something. It was kind of hard to follow.

"Well," he said, "as an amateur meteorologist, let me assure you, it rains in November, and it rains in mid-October. You can get warmer weather as the fall goes on."

Nobody really had any idea what he was talking about. Bud had that same beautiful look on his face when he sat in front of Congress to talk about a steroid mess that he had not seen coming. He had that same look when he sat in front of reporters and talked about why the 2002 All-Star Game had ended up a tie. He had that same look when he was trying to explain what was happening during that awful baseball year of 1994 when the players went on strike, and he had to cancel the World Series.

You may think I'm joking when I call that puzzled look "beautiful," but over time I have come to genuinely like Bud Selig, for all his quirks. I have not often agreed with his decisions, but in looking back it seems that often he was right and I was wrong. I thought the wild card would steal some of the tension out of pennant races, and to some extent it has. But it has added its own tension too, and most people really like it. I thought that interleague play was a gimmick that would lose its freshness after a few years, and to some degree it has. But it's still an event when the Cubs play the White Sox, the Mets play the Yankees, the Royals play the Cardinals.

I thought that Bud would never get his arms around the steroid problem, but now the sport probably has the strongest testing policy in pro sports. I thought that it was dumb to give the All-Star Game winner homefield advantage in the World Series ... but it's certainly no dumber than the longstanding policy of just alternating years, and anyway it has added just a touch more interest to the game.

I thought Bud was too partisan and too insensitive to govern the uneasy peace between owners and players. But suddenly you look and baseball has not had a strike since 1994, and everybody seems to be making money.

So yeah, in the end, I've come to like that confused look because there's something real about Bud Selig. People often comment how he just doesn't seem like a commissioner, he doesn't have any of the polish of NBA commissioner David Stern or the cool forcefulness of NFL commissioner Roger Goodell. That's no doubt true. He still babbles off point, he gives himself powers that nobody seems to believe he has, he stubbornly insists that sometimes the weather gets better later in the fall.

But more and more, in this age of pre-packaged candidates and prepared statements and tortured spinning of every word, Bud Selig seems more to the point. He is incapable of politics. He is sensitive to every criticism. He does not look his best during a crisis. He is just trying to do the right thing. He seems a whole lot like me and just about everybody I know.

"If I told you tonight what I think of meteorologists ...," Selig grumbled as he tried to explain why they had even tried to play Monday night's World Series game. The meteorologists, apparently, had given Bud a bum forecast, one that called for very light rain throughout the night. The rain was not light at all.

And so, while one of those other slick commissioners or practiced politicians would have been up on the podium speaking in platitudes and ducking the subject, Bud Selig sat up like every American guy in every barber's chair who has ever had a picnic or an afternoon of golf rained out, and he blamed the weatherman.

"Had it been what three different weather services told us it would be," the commissioner of baseball muttered with a little edge in his voice, "we'd be at the end of the game right now. And we wouldn't be sitting here."