When signing a Dominican prospect, it's buyer beware

SANTO DOMINGO, Dominican Republic -- The kid's mother had no teeth. The baseball scout sat with her in her home in the small village, trying to decipher the sounds she was making. The unintelligible words made his job even tougher. It used to be that a scout's role was to identify a player -- could he hit, run, throw and catch? -- but as he sat across the table from the woman trying to understand her, the scout was engaged in what has become the newest part of his job: literally trying to identify a player.

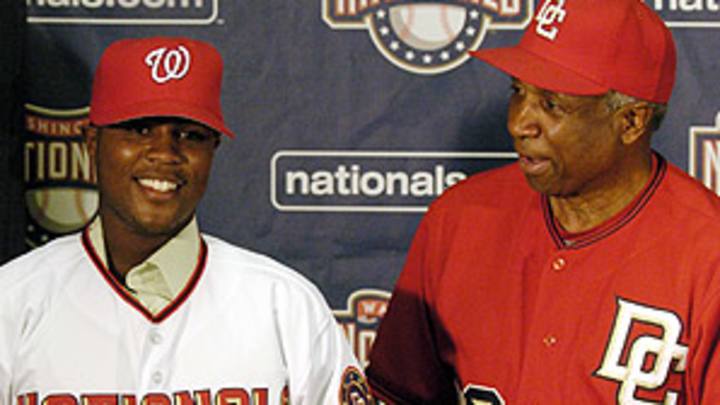

When signing a teenage prospect, scouts in the Dominican Republic have always worried about what they might get, but now they must worry about who they might get. Two weeks ago SI.com revealed that Washington Nationals prospect Esmailyn Gonzalez, who had been signed to a team-record $1.4 million bonus in 2006, was really Carlos Alvarez, and that he was four years older than he had been purported to be. In the wake of the scandal Nationals general manager Jim Bowden resigned and Bowden's special assistant, Jose Rijo, was fired.

Teams have long sought to verify the identities of Latin American prospects before doling out signing bonuses and finalizing contracts. Because age 16 to 17 is the sweet spot for such prospects -- and therefore the period when they stand to make the most money -- many players and their handlers are willing to alter documents to make them appear younger or, in rare cases, older. Teams would often not discover the fraud until long after signing such players, after the clubs had housed and fed them in their Dominican academies for a year or two. When the prospects developed enough to join farm teams in the U.S., the clubs would apply for a work visa for them, only to have officials at the U.S. consulate discover fraudulent birth records.

In 2003 Major League Baseball made a move to tackle identity and age fraud when the commissioner's office in Santo Domingo contracted with local private investigators to verify information about potential signees. But now, six years later, many major league teams are complaining about the system, describing the investigations as perfunctory, riddled with incompetence and subject to the very corruption that they were designed to stop.

After news broke of Gonzalez's true identity, his handler, Basilio Vizcaino, Rijo and Nationals assistant general manager of player development Bob Boone blamed the Dominican investigators who had been subcontracted by MLB. "The thing that seems most unfair to me is how bad the vetting process is down there in the Dominican for the ages of young players," Boone told The Washington Post. One scout told SI, "If [Esmailyn Gonzalez's] investigation comes back and he's 20 instead of 16, he goes from a $1.4 million signing bonus to 10 grand."

SI interviewed front office personnel from five major league teams this week; four said that they had lost money on players who had passed the investigations conducted by MLB subcontractors but were later determined to be a different age, person or both. Last Tuesday the commissioner's office in Santo Domingo summoned the Dominican academy directors of all major league teams to a meeting. There, Ronaldo Peralta, the head of MLB's Latin American office, apprised them of overhauls in the investigations process, and announced the hiring of new investigators and the firing of others. Ironically the dismissed investigators were some whom teams respected most (teams had been free to choose which investigators worked on their cases).

Two of those let go, according to MLB's vice president of international operations, Lou Melendez, "got too much work and got sloppy." Under the new procedures MLB would assign the investigators, and clubs would no longer be able to pay for investigations in cash -- each costs from $300 to $600, depending on the amount of work involved. The latter change comes after an employee in the Santo Domingo office was fired for the "mishandling of funds," according to Melendez.

It marked at least the second round of investigator dismissals in the past year. Last spring Major League Baseball terminated three investigators. Among them was Jose Antonio Frias, Peralta's brother-in-law, who was dismissed for accepting a bribe to fix an investigation, according to Melendez and two other sources familiar with the investigation. Frias declined to comment to SI, citing a confidentiality agreement that he said he had signed with MLB. Says Melendez, "That was one guy. To leave the reader with the conclusion, 'Oh, it was his brother-in-law [so Peralta] must be on the take, too,' would be really wrong because he's not. He and his wife, they were destroyed by this." Peralta agreed to SI's interview request on Sunday morning, pending approval from MLB vice president of public relations Pat Courtney, but Courtney e-mailed SI on Sunday night to say that Melendez's comments were all that Peralta and baseball would have to say on the matter.

"Who's the person who put [Frias] in that position? Ronaldo Peralta," says one scout. "And who's crying for the Lerner family [owners of the Nationals] or for those teams who have lost money?" The scout says that the investigations his team paid for that were conducted by Frias have had to be conducted and paid for again because the U.S. consulate -- which requires reports of the investigations to accompany all prospects' work visa applications -- has rejected the initial reports. The scout says that a couple of his team's prospects, already under contract, are tangled up in visa issues because of suspect investigations.

Scouts say that the investigations aren't just needed to protect owners' investments, but also to safeguard scouts' reputations. A prospect who is older than he says may dominate his younger opponents. Alvarez, for example, won the Gulf Coast League MVP award and batting title, hitting .343 last season. Says one scout, "I have to look at these kids and say, 'Wait a minute, those kids aren't 18.' But my boss is looking at the numbers saying, 'Where were you on this kid?'"

Attempted fraud in the Dominican Republic has skyrocketed along with the number of prospects from the country and the money being paid to them. In 1990 major league teams signed 281 players and issued roughly $750,000 in signing bonuses to Dominican prospects. By 2008 more than 400 players had inked deals, receiving roughly $45 million in bonuses. "When you have that much money going into a country and you have buscones [street agents] who will stoop to any means to perpetuate [fraud], anything is possible," says Melendez. MLB now subcontracts with six Dominican investigators, all of whom are trained by the U.S. consulate and have backgrounds in law or law enforcement. The dismissed investigators, however, had similar qualifications.

Arlina Espaillat Matos, an attorney, conducted investigations for big league teams for six years until last month, and she says that the work is far more difficult than it may seem. The Dominican Republic has few computerized records. Birth certificates in many places are still handwritten and kept in binders. In some remote villages Espaillat Matos cut through sugarcane fields to talk to prospects.

In one tiny town she says she walked into a store and approached a woman working behind the counter. When she asked the clerk the name of the boy whom the shopkeeper had supposedly known all of her life, the woman peeked down at a piece of paper she was hiding beneath the counter. "It looked like a WANTED poster," Espaillat Matos says. "It had a picture and a name, a birth date and a list of answers to questions an investigator might ask." When Espaillat Matos asked about the names of the boy's parents, the clerk's eyes darted back to the flyer, which Espaillat Matos later learned had been handed out all around town, along with an appeal to not so much lie for the boy but to help him achieve his baseball dreams and a big league paycheck.

In her career vetting Dominican prospects, Espaillat Matos says that she encountered doctored hospital records and school documents, as well as school principals and neighbors who had been paid off to swear that a prospect was who he said he was and was as young (or old) as he claimed. The toughest cases, she says, are when a player -- usually at the insistence of his buscon -- assumes someone else's identity by using that person's school report cards and vaccination and baptismal records.

"There is so much money [in signing bonuses] now that the entire town can be paid off," Espaillat Matos says. Some of that money, she says, has been offered to her to falsify a report. She says she has never taken a bribe.

Today's large stakes have inspired ingenious schemes, however. In recent months scouts say they've seen a rash of Dominican prospects posing as Haitians. Records in Haiti, the neighboring country and the poorest in the Western Hemisphere, make paperwork in the Dominican Republic look organized. A Haitian birth certificate is easier to alter and harder to verify.

Melendez says the investigations are reducing fraud, and points to a significant drop-off in voided contracts as evidence: 60 percent when the investigations started in 2003 compared to roughly 17 percent today. Some of that decline, however, may be due to more sophisticated schemes that haven't been caught by MLB or the consulate. Alvarez, after all, received a visa to play in the U.S. for two minor league seasons. Melendez also trumpets a new policy that suspends for one year players who are caught with fraudulent paperwork.

Several scouts interviewed by SI suggest that once a player has been revealed to have used false papers, all teams should be notified. Currently that information is proprietary, due to the competitive nature of scouting, and the results of investigations are not shared among teams. Melendez says that MLB has proposed sharing reports of investigations in the past but that teams fought it, not wanting to tip their hands about which players they were scouting. Says Melendez, "The office [in the Dominican] wasn't set up as an investigatory office. Their job was to regulate the business of doing baseball in Latin America, to enhance MLB's image in Latin America."

Staff Writer, Sports Illustrated Staff writer Melissa Segura made an immediate impression at Sports Illustrated. As an undergraduate intern in 2001, her reporting helped reveal that Danny Almonte, star of the Little League World Series, was 14, two years older than the maximum age allowed in Little League. Segura has since covered a range of sports for SI, from baseball to mixed martial arts, with a keen eye on how the games we play affect the lives we lead. In a Sept. 10, 2012, cover story titled, The Other Half of the Story, Segura chronicled the plight of NFL wives and girlfriends caring for brain-injured players. In 2009 she broke the story that MLB had discovered that Washington Nationals prospect Esmailyn Gonzalez, who had been signed to a team-record $1.4 million bonus in 2006, was really Carlos Alvarez and he was four years older than he had claimed to be. Segura graduated with honors from Santa Clara University in 2001 with a B.A. in Spanish studies and communications (with an emphasis in journalism). In 2011, she studied immigration issues as a New York Times fellow at UC-Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism. Before joining SI full-time in 2002, she worked for The Santa Fe New Mexican and covered high school sports for The Record (Bergen County, N.J.). Segura says Gary Smith is the SI staffer she would most want to trade places with for a day. "While most noted for his writing style, having worked alongside Gary, I've come to realize he is an even more brilliant reporter than he is a writer."