Major conference tourney champs not an indicator of NCAA success

North Carolina, the freshly crowned ACC regular-season champion, will advance to the NCAA tournament for the 41st time -- probably as a No. 1 seed -- regardless of how the Tar Heels do in this week's conference tournament, which begins Thursday in Atlanta. That much is certain.

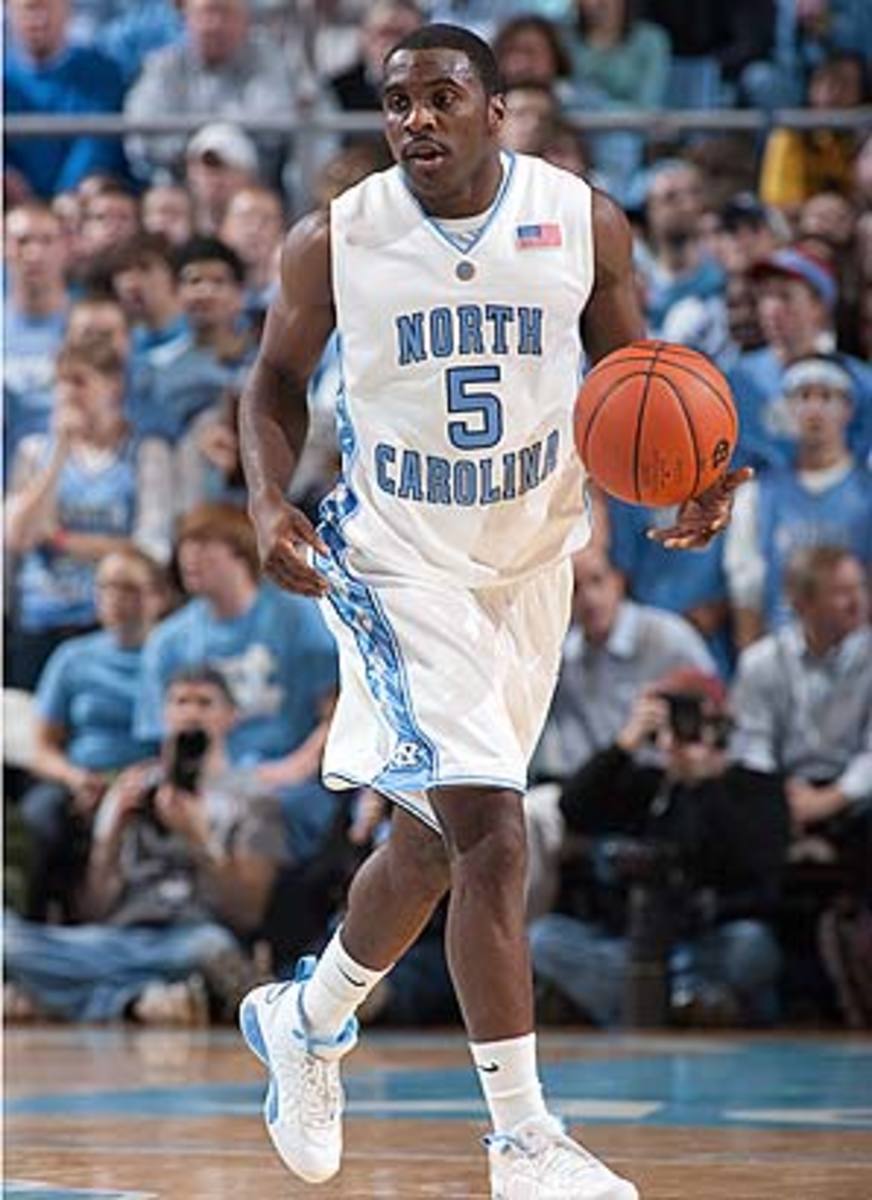

But what's less clear is the future health and effectiveness of point guard Ty Lawson, who left practice last Friday with the aid of a crutch after injuring his left big toe. X-rays were negative, and he certainly did not seem limited too much Sunday night, scoring 13 points dishing out nine assists and grabbing eight rebounds in a 79-71 win over Duke. But the risk of re-injury is always present.

Lawson is the motor that runs the Tar Heels offense. He averaged 16.0 points and a league-leading 6.4 assists per game during the regular season, and his importance was underscored last year when he missed six games with a sprained ankle. In his absence, UNC lost to Duke (one of only three losses all season), needed double overtime to beat Clemson and slipped past woeful Virginia by a point.

Now the Tar Heels are facing the prospect this week of playing three games in as many days to repeat as conference champs. Should Lawson play his usual 29.4 minutes per game and risk further injury with great NCAA positioning already assured? After all, only four of the ACC's last eight national champions won the league tournament.

"I do think there's a lot of pressure and a lot of emphasis placed on the ACC tournament," UNC coach Roy Williams said last week before Lawson's toe injury. "To me, it's draining for you."

And the broader question is, for a bonafide national title contender, a school that has locked up a high seed in the NCAA bracket, how much is there to gain by exerting itself to win a conference tournament?

The NCAA opened the Division I tournament field to more than one team from each conference in 1975 (and expanded the bracket to 64 teams in 1985). In the 34 seasons since, the importance of winning the league draw as a predictor of NCAA success has declined.

Consider this downward trend: From 1975 to '86, 18 of the 25 Final Four teams (72.0 percent) who played in a conference tournament won it. But since 1993, less than half (28 of 57, or 49.1 percent) of all Final Four teams won their league's postseason. Seven national champions have failed to win their conference tournament, including three this decade (Maryland in 2002, Syracuse in 2003 and North Carolina in 2005). Last year was a tournament anomaly, not only because it was the first time all four No. 1 seeds reached the Final Four, but also because it was also the first time since 1983 that each semifinalist won its league tournament.

Williams has led two North Carolina and four Kansas teams to the Final Four -- and last year's Tar Heels were the first of the six to win their league tournament. "The conference tournament is great for everybody financially," Williams said. "It's great for the fans. I'm not so sure it's great for the players or the coaches, [because] you have to adjust everything in your NCAA preparation depending on how well you did at the conference tournament."

Here are three main reasons why the league postseason has declining meaning for March Madness:

• Conference tournaments take a toll. Though physical fatigue is unlikely to carry over into an NCAA first-round game on Thursday or Friday, it can affect practice on Monday and Tuesday, which "may hurt your preparation," West Virginia coach Bob Huggins said.

And, of course, injuries happen. Huggins, who was Cincinnati's coach in 2000, saw that firsthand when Kenyon Martin, the consensus national Player of the Year, broke his leg three minutes and four seconds into a Conference USA quarterfinal. Cincinnati was playing St. Louis, a school it had defeated by 43 points just five days earlier, but lost that game without Martin and effectively ended the No. 1 Bearcats' national title hopes. (Tulsa upset Cincy in the second round of the NCAAs). "Kenyon breaking his leg was furthest thing from anyone's mind," Huggins said.

In 2006 Syracuse made a miracle run through the Big East tournament, winning four straight days at Madison Square Garden to lock down an NCAA berth. But five days later, with Orange star Gerry McNamara hobbled by a leg injury worsened in Big East play, Syracuse was upset in the first round; McNamara failed to score a field goal.

• There's more parity in the NCAA bracket. Winning a league such as the ACC or Big East is no longer a strong gauge of a team's national standing. With more teams like George Mason in 2006 and Davidson in 2008 lurking in the bracket, this rise of mid-majors has decentralized basketball's power structure away from the BCS conferences. Though no mid-major has won the national title, there's less predictability in the NCAA draw.

• Not all conference tournaments are created equal. Final Four teams from the BCS conferences are far less likely to have won their league's postseason (41 of 79, or 51.9 percent) than teams from the other conferences (15 of 21, 71.4 percent). BCS leagues have more depth, and many mid-major conferences -- 13, including George Mason's Colonial and Davidson's Southern Conference -- conclude their tournaments the weekend before Selection Sunday. George Mason had 12 days to rest and prepare for its first-round NCAA game; Davidson had 11 days off before the Big Dance and upset the Big Ten tournament champ, Wisconsin, in the Sweet 16.

For North Carolina and for any of the this year's grab-bag of top teams, they should be sure to keep their eyes on the real prize, which doesn't take place this week.