Jordan's historic day in Boston gave rise to Hall of Fame leader

I was 24, Michael Jordan was 23. He was sitting on a padded table in the trainer's room at the Chicago Bulls' practice facility in 1986, a few days before he would score an NBA-record 63 points in a playoff game at Boston.

He was telling me the story of how he had forced the Bulls to let him play. In the third game of his second NBA season, he had landed awkwardly on his left foot and broke the navicular tarsal bone in front of his outer ankle. It was a clean break of the same tiny bone that had ruined Bill Walton's career.

"Basketball took up 90 percent of my day," he said. "It made up my routine. It was hard for me to cope."

Jordan left Chicago in order to heal in North Carolina. He was in a walking cast the day after Christmas and fitted with nothing more than a brace in January. Before the Bulls knew it -- long before -- he was playing pickup games with friends in Chapel Hill.

"It was the type of atmosphere I wanted," he said. "I didn't want someone hovering over me, looking at me, waiting for me to get hurt."

He was five years away from the first of his six NBA championships. There were no charts of progress, no trainers or doctors with a plan for each afternoon. He wore whatever sweats happened to be clean, lifted weights, then played every day until he was exhausted. The only big-time touch was the shoes wearing his name. "Those games were how I got my confidence back," he said.

He returned to Chicago for a CT scan that revealed what he already knew: The foot was healing properly. He told Bulls general manager Jerry Krause that he had been playing full-court games in North Carolina. "He didn't believe me at first," Jordan said. A Cybex test proved that the muscles in Jordan's injured left leg were stronger than those in his right. In March, he requested a meeting with hesitant Bulls administrators and three doctors, in hopes of persuading them to let him play.

While Walton had suffered a stress fracture, Jordan had been the victim of a single freak accident, the only major injury he would suffer in a lifetime of basketball from public school through 15 NBA seasons. He wondered if management would take him seriously. "I have a boyish face," he said in 1986. "I look young."

He appeared at the meeting behind clear, non-prescription glasses "to look older and let them know I was serious." He wore sweats "to let them know I've been lounging around, ready to play." He listened to the doctors proclaim there was a 10 to 20 percent chance that he would reinjure the foot.

"Everyone's talking about the 10 percent risk," Jordan said. "What about the 80 to 90 percent chance that it will be a success?"

Bulls owner Jerry Reinsdorf stared at Jordan. "Let's say you've got a headache and you have a bottle of Tylenol," Reinsdorf said. "Let's say one of the 10 pills has cyanide in it. Sure, there's a 90 percent chance of success, but are you willing to take that 10 percent risk?"

"That's a good example," Jordan said, "but I don't have a headache."

He was reactivated two days later, having agreed to play a restricted amount of each game. The Bulls lost the first five games of his comeback while he was trying to accomplish too much in his short window of playing time. Other games were lost when he was benched in the fourth quarter.

"It was ludicrous," Jordan said. "Nobody really understood my point of view. I took everything into account. I saw the risk. If I'm willing to accept that, then somebody should back me up. I'm smart enough. I'm able to make my own decisions."

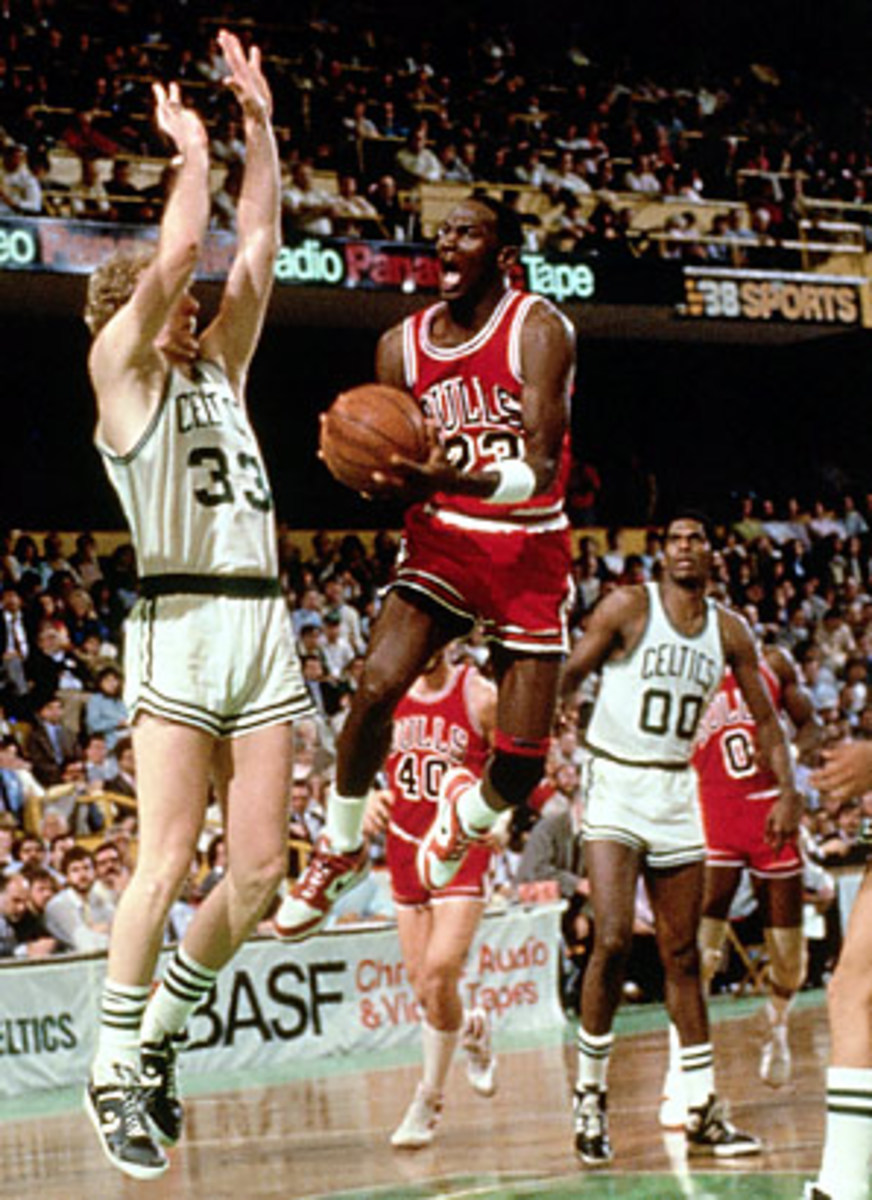

The Bulls were a 32-win playoff team and trailed 1-0 in the first-round series when Jordan led them into the old Boston Garden for Game 2 against the eventual champion Celtics. Of all that he would ever accomplish -- the nine championships in college, professional and Olympic basketball, the duels with would-be rivals and the virtuoso performances that come to mind with his entry to the Hall of Fame -- I am most glad I was there for his afternoon in Boston. Twenty-three years later and I have yet to see anything quite as dramatic as Jordan's clearing the rim in a blink. He rose up there from down here with no visible in-between. Each leap drew gasps from a full house that had no interest in watching him succeed yet sat mesmerized nonetheless. He dunked like a frog's tongue snapping at flies.

I also remember that he was a gentleman. We spent at least an hour and a half discussing his story, and on the eve of his coming-out party in the Garden he came over to thank me for the article I had written in the Boston Globe about his injury and recovery.

"Last year I probably would have been more passive through something like this," he told me in 1986. " As I get older, I'm going to take more and more leadership."

He was just beginning to realize himself.