The changing perception of Federer

The most painful thing for a champion is when you realize that someone else has passed you by.

The most difficult thing for a champion is to try to change your game. After all, you became the best playing this way. Change what works? No, the hubris of having become the best almost demands that you stay the course. Or you quit.

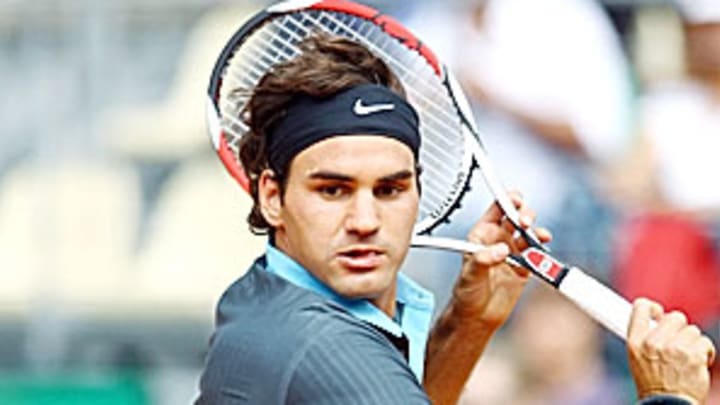

And so we have ... Roger Federer.

It was hardly but a year or so ago when the only question was whether he was the greatest tennis player of all time. And there was no argument whatsoever that his game was the loveliest ever. But now it seems that he might not even be the best of his own era.

How quickly it has happened. How bizarre. Federer is, after all, still ranked second in the world. It was only last September when he won his 13th Grand Slam tournament, at the U.S. Open. He's been in 14 of the last 15 major finals. That's otherworldly. No, he's not a tragic figure. Away from the court, he appears level and happy, a newlywed with a baby on the way. He's rich and healthy Even, it seems, rather quite a normal human being.

And yet, now he is demonized. Federer could not beat Rafael Nadal on clay in the French Open. Then, at Wimbledon last summer, Nadal beat Federer on grass. And at the Australian Open four months ago, Nadal overpowered him on hard courts. And suddenly, Roger Federer didn't own a court anymore. Who had ever seen a champion lose his world so visibly, so sorrowfully as he did in Melbourne this year? The tears flowed, as Nadal tried to console him. "God, it's killing me," Federer moaned, turning away from the microphone.

Looking back, it's almost eerily the same as what happened to Bjorn Borg, whodominated the game as much in the late 1970s as Federer these past few years. But just as Federer cannot win the French on clay, Borg could not win the U.S. Open on hard courts. And when John McEnroe took Centre Court at Wimbledon away from Borg and then beat him once again in New York, Borg walked away from the game at age 26. He was still great, but someone had solved him. And, well, that was killing him.

Everybody has advice for Federer. Get a coach, Roger. Use a larger racket. Whatever, change. Do something new, Roger. Do something different. But maybe it's hardest for him to adjust because he knows what everyone has told him, that he is the most beautiful tennis player who ever lived.

And then, Sunday, in Madrid, in the last tune-up for the French Open, Federer beat Nadal. On clay. Straight sets. Granted, Nadal had a sore knee, and he was worn down from a grueling semifinal against Novak Djokovic. Still, is it possible this one victory can restore Federer's confidence?

Power rules almost every sport today. It is all that is stylish. Nadal is power. Beauty is now but a bagatelle. How do you get prettier when you are already the fairest of them all, and that isn't enough anymore?

Frank Deford is among the most versatile of American writers. His work has appeared in virtually every medium, including print, where he has written eloquently for Sports Illustrated since 1962. Deford is currently the magazine's Senior Contributing Writer and contributes a weekly column to SI.com. Deford can be heard as a commentator each week on Morning Edition. On television he is a regular correspondent on the HBO show Real Sports With Bryant Gumbel. He is the author of 15 books, and his latest,The Enitled, a novel about celebrity, sex and baseball, was published in 2007 to exceptional reviews. He and Red Smith are the only writers with multiple features in The Best American Sports Writing of the Century. Editor David Halberstam selected Deford's 1981 Sports Illustrated profile on Bobby Knight (The Rabbit Hunter) and his 1985 SI profile of boxer Billy Conn (The Boxer and the Blonde) for that prestigious anthology. For Deford the comparison is meaningful. "Red Smith was the finest columnist, and I mean not just sports columnist," Deford told Powell's Books in 2007. "I've always said that Red is like Vermeer, with those tiny, priceless pieces. Five hundred words, perfectly chosen, crafted. Best literary columnist, in any newspaper, that I've ever seen." Deford was elected to the National Association of Sportscasters and Sportswriters Hall of Fame. Six times at Sports Illustrated Deford was voted by his peers as U.S. Sportswriter of The Year. The American Journalism Review has likewise cited him as the nation's finest sportswriter, and twice he was voted Magazine Writer of The Year by the Washington Journalism Review. Deford has also been presented with the National Magazine Award for profiles; a Christopher Award; and journalism honor awards from the University of Missouri and Northeastern University; and he has received many honorary degrees. The Sporting News has described Deford as "the most influential sports voice among members of the print media," and the magazine GQ has called him, simply, "The world's greatest sportswriter." In broadcast, Deford has won a Cable Ace award, an Emmy and a George Foster Peabody Award for his television work. In 2005 ESPN presented a television biography of Deford's life and work, You Write Better Than You Play. Deford has spoken at well over a hundred colleges, as well as at forums, conventions and on cruise ships around the world. He served as the editor-in-chief of The National Sports Daily in its brief but celebrated existence. Deford also wrote Sports Illustrated's first Point After column, in 1986. Two of Deford's books, the novel, Everybody's All-American, and Alex: The Life Of A Child, his memoir about his daughter who died of cystic fibrosis, have been made into movies. Two of his original screenplays have also been filmed. For 16 years Deford served as national chairman of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and he remains chairman emeritus. He resides in Westport, CT, with his wife, Carol. They have two grown children – a son, Christian, and a daughter, Scarlet. A native of Baltimore, Deford is a graduate of Princeton University, where he has taught American Studies.