Iowa's Harrison Barnes storms onto national stage as top recruit

CHARLOTTESVILLE, Va. -- Late one morning a few weeks ago, Stanford coach Johnny Dawkins was showing Harrison Barnes, the nation's top basketball prospect, around campus when he looked at his watch. It was 11:15. Their next meeting was at 11:30 with "Professor Rice." Punctuality, Dawkins stressed, was important to the faculty.

Barnes's mother, Shirley, who works as a secretary in the department of music at Iowa State University, asked which subject the teacher studied. Dawkins smiled. "Oh, it's Condoleezza Rice," he said. "You probably saw her in our brochure."

The former Secretary of State's name caught Harrison off guard. He dropped the cup of water he was holding in his left hand. A cookie he was holding in his right followed. "I was a little taken aback," says Barnes, who holds a 3.4 GPA and writes out academic questions in a notebook before visits to colleges. "I didn't want to gawk, but she was the world's third most powerful person."

Barnes is a natural networker. Before attending the NBA Players' Association Top 100 Camp at the University of Virginia last week he was to be fitted for golf clubs, but the social climber had to postpone due to the flu. On his summer reading list is Secrets of the Mind of a Millionaire: Mastering the Inner Game of Wealth. To pay for his travel to summer AAU tournaments, the budding entrepreneur mows lawns, shovels driveways and sends out handwritten fundraising letters. "He finds a goal," says Vance Downs, who coaches him at Ames (Iowa) High, "and then he's unforgiving in pursuit."

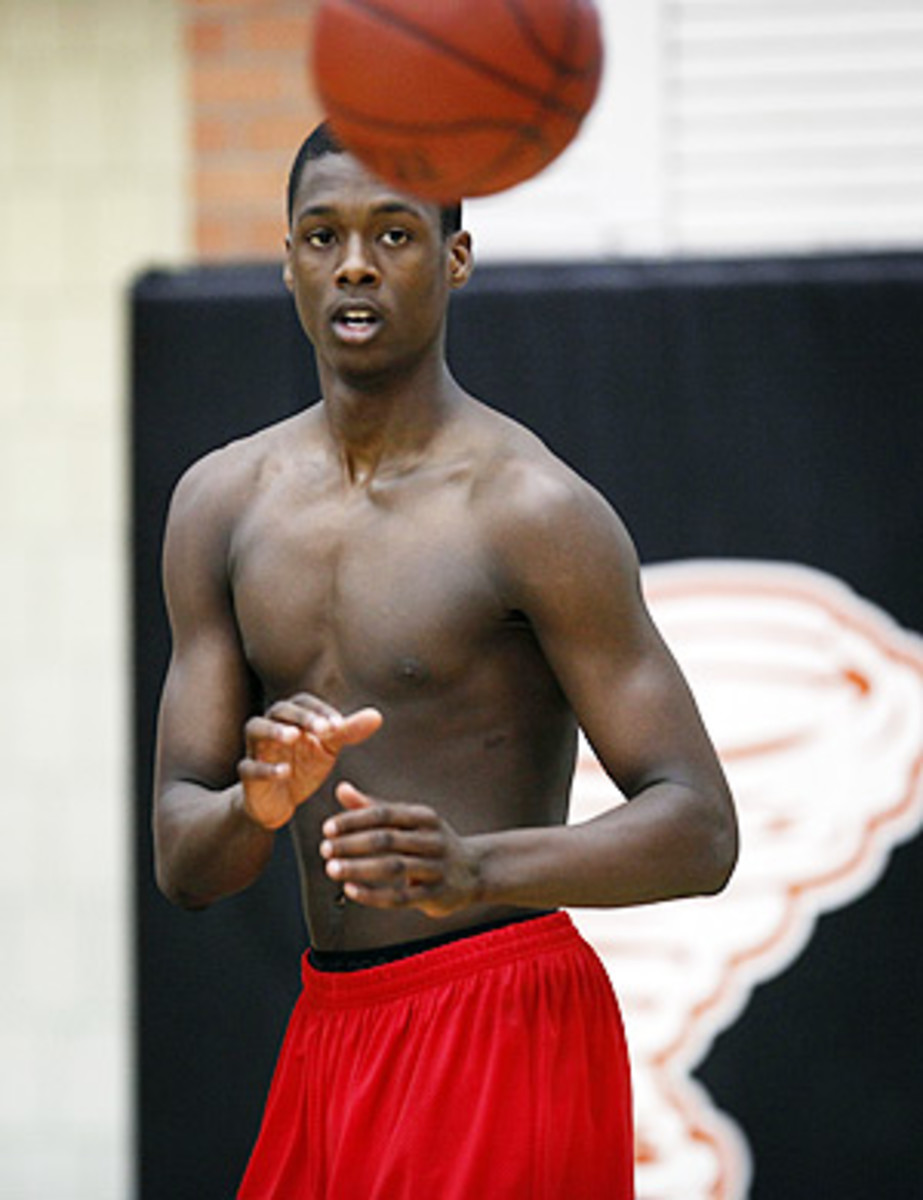

College coaches have been chasing the 6-foot-6 swingman for two summers. The hometown Cyclones were the first to offer a scholarship, and the rival Hawkeyes followed suit. After terrorizing opponents with his rebounding, ballhandling and 6-11 wingspan at the Nike Hoops Jamboree last spring, he returned to a flood of interest. Before leaving that weekend, his mother had asked a neighbor to collect the family's mail. Upon their return, 50 letters from one school alone had piled up.

Shirley planned for her son's success before he was conceived. In 1987, she started taping Chicago Bulls game to store Michael Jordan's greatness in the case she one day had a son. She would sit in front of the television with her remote control, pause recording during commercials to save space on the VHS tape and return once play resumed. The practice continued well past Barnes's birth on May 30, 1992, when he was named Harrison Bryce-Jordan Barnes. The taping stopped only after the legend retired for good.

Barnes's electric moves made him a star three years ago. As a Little Cyclone at the only high school -- public or private -- in Ames, Barnes swept past his freshman competition on the first day of tryouts. Downs phoned his mother that night and asked permission to bump her son to the varsity. When she saw her son that night, she said nothing of the conversation. As he packed for school, though, she made a subtle suggestion. Freshmen practiced later than the varsity, allowing him time to return home between dismissal and taking the court. Still, she said he should bring his sneakers. Ever obedient, he did not question. After classes, Downs informed him of the change. A smile broke across Barnes's face. "I should have known," he says.

Within a week an assistant called Downs to the side of the court where big men were being drilled. All of 14, Barnes's footwork proved steps ahead of his teammates'. Downs pivoted and walked away in amazement. "I couldn't let him know how impressive that was," the coach says.

The boy with the Baptist upbringing and the burnished grades (five advanced placement courses including physics) has made believers of locals and national talent appraisers alike. After losing the state championship game on a 16-foot buzzer beater as a sophomore, he showed up at the school gym the next morning before six o'clock. Downs, who had told his players to take time off, awoke to a missed call from his star a few hours later. He wanted to be let into the gym. "We're not going to win a title by taking days off," said Barnes, who led the way to last winter's title win.

Barnes hasn't played much high school ball outside Iowa. State association rules prohibit schools from scheduling more than 21 games in a regular season and limit out-of-state travel to Illinois, Nebraska, South Dakota, Missouri, Wisconsin and Minnesota. Exposure will come in mid-December when ESPN broadcasts a game. "My jaw just about dropped to the desk," Downs says of hearing about the telecast agreement.

Still, coaches have come to Iowa to see Barnes. In January, North Carolina coach Roy Williams had taken off from Chapel Hill to observe a game against Fort Dodge High when the contest was canceled due to weather forecasts calling for a "ground blizzard". Winds had picked up and though there was not a snowflake in the air at the time of the cancellation, visibility was expected to make roads impossible to navigate.

Unannounced drop-ins can add a dash of surprise to the process, too. While in North Carolina last October, Barnes and his mother visited Duke. "Sometimes it's good to see how things are when there are no plans to see you," the mother says.

On the first day that coaches could be on the road in April, there was Williams with assistant Steve Robinson fresh off their second national title . NCAA rules forced the early birds to sit inside their SUV for a while but when the magic hour arrived, the two entered the lobby to awestruck Iowans, who asked for autographs.

Barnes knows how to calm the corn-fed crowds. Following a win at Mason City -- the team's longest road trip at two hours -- the star did not want to leave until each signature request was met. A teammate threw a jacket over his head and hurried him onto the bus with an Almost Famous feel. "It's a bit of a circus at times," says Downs, who noted standing-room-only crowds at each game.

The showmanship traces its roots to his mother's early lessons. Around choral and band sessions at her office since he was a child, he picked up the cello first and considers Beethoven's Für Elise his favorite music to play on the saxophone. Still, all the resume-building, from his membership in DECA -- an international association for students interested in marketing and entrepreneurial activities -- to his self-founded bible study group , Word on Wednesday, have led him to this point. Eleven schools remain on his watch list. "It would be premature to say there is a favorite at this point," says Barnes, who visited UNC last week before flying home from the NBAPA camp.

The words "I don't know" have always been taboo in the two-story starter home Barnes shares with his mother and 10-year-old sister Ashle Jourdan. Self-sufficient since childhood, his mother's mandate has always been for him to figure things out on his own. When coaches call, she defers to the decision maker. "They need to have that relationship with Master Harrison," she says.

One assistant, who the family will not name, pens handwritten letters. "They never get lost in the pile," Shirley says.

In basketball, as in business, Barnes knows how far the personal touch can go.