Media glare continues to suffocate Brazil's stars

In the 1974 World Cup Brazil took such a beating from Holland that four years later it was obsessed with imitating the "total football" of the Dutch, with their constant positional changes and intense pressure on the ball. It didn't work. As one Brazilian journalist commented, "in a team game like soccer you need to have the right cultural base to introduce modifications."

But there's another plant from Holland that is thriving in Brazilian soil -- the reality show TV programme 'Big Brother,' where previously anonymous citizens are confined in a house and gradually eliminated by the viewing public. Developed by a Dutch company, the format has proved a global success -- but especially in Brazil, where the 10th version of the show has just come to a close. The recent grand final attracted nearly 155 million votes, announced as a world record for this type of programme. "Big Brother Brasil" grips the country with extraordinary intensity. Over the last few weeks it has been a constant theme of conversation at bus stops and in bars.

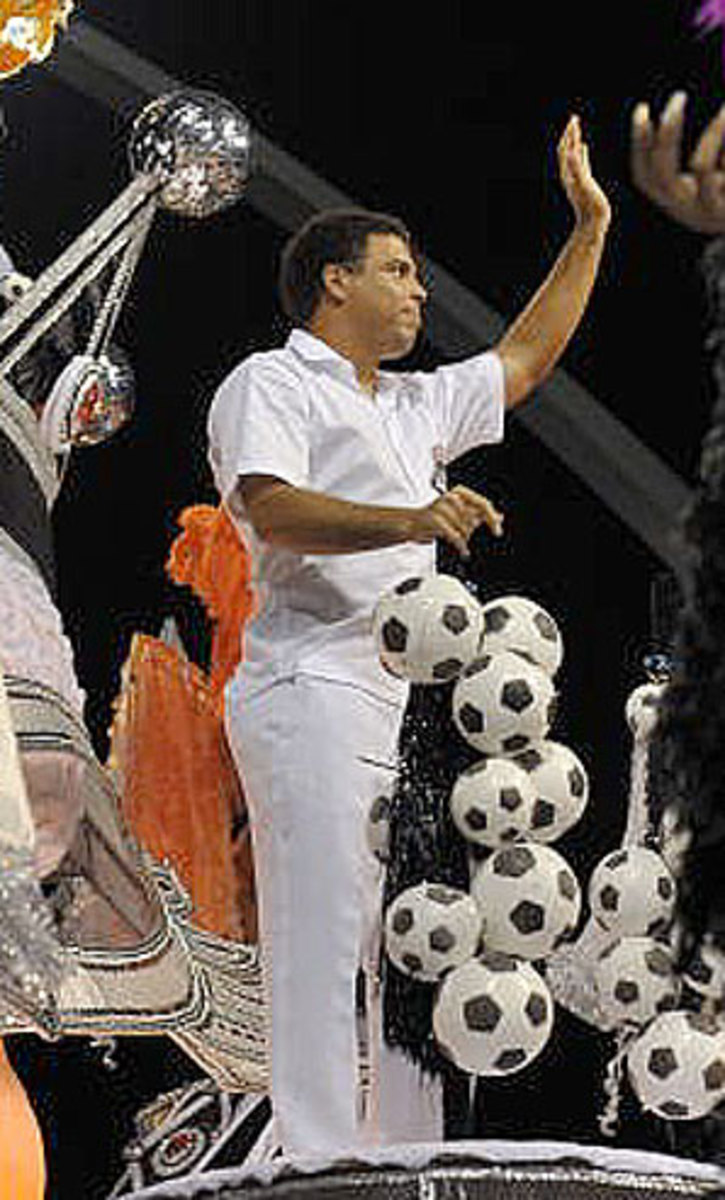

And, I'm sure, in the locker rooms of top soccer clubs. Many players are fans of the show. One of the illustrious visitors to the show's house this year was the great Ronaldo, currently, of course, with Corinthians in Sao Paulo. He showed that he had been following closely the antics of the "brothers," and told them that he could easily relate to the sense of claustrophobia inevitably bred by being confined in the house. It is hardly surprising. Soccer players spend a lot of time copped up, especially in Brazil. As well as the travelling there is the "concentracao," the period of time they are locked up in hotels before each match. It can put a strain on relationships. Ronaldo told the "brothers" that he had found it difficult to share a room with his old friend Roberto Carlos during the squad's preseason work. It meant putting up with the great left back's rusticated taste in Brazilian country music.

But the forced and confined co-existence is not the only point of identification between the reality show participants and big-name soccer players. There is also the constant invasion of their lives. The cameras are always watching -- as Flamengo's high-profile strike duo of Adriano and Vagner Love recently discovered.

Both of them had to give statements to the Rio police to explain alleged links with drug dealers. Vagner Love was filmed on his way to a dance in one favela (Rio's improvised hillside neighbourhoods) with what appeared to be an armed escort from the drug trade. Adriano, meanwhile, was asked to clarify how a motorbike he had allegedly bought came to be registered in the name of the mother of a drug dealer from another favela.

As it happens, both of these players have roots in the favelas, where the historic absence of the state has left a power vacuum often filled by the drug dealers. They have grown up with people who have chosen this way of life. The majority of Brazil's soccer players, though, are not favela kids. Many come from the suburbs -- forget the North American link with affluence. These are the working-class districts on the periphery of the big cities, where, as the rich areas and therefore the consumers are further away, the drug trade is not so intense. Even so, some high profile players from these areas are known to have links with drug dealers. National team goalkeeper Julio Cesar was asked to explain himself on these grounds to the Rio police a few years back. Another current Brazil international allegedly went through a phase of dedicating some of his goals to a drug dealer.

The mutual fascination is perhaps not hard to understand. In "King of the World," one of the all-time great sports books, David Remnick explains that "the underworld likes boxing because boxers themselves are outsiders ... since boxers come into the game from the margins, they are approachable by men from the margins of business." Much of this applies to soccer players in a land like Brazil, with vastly unequal income distribution and a precarious welfare state. National team coach Dunga likes to motivate his big stars by reminding them that before they made their names nobody ever gave them anything for free. The drug dealers feel the same way. They too have made their climb the hard way.

And so the drug dealers and some of the soccer stars form a kind of alternative aristocracy. The players lead very regimented lives -- full of training sessions, trips, games and the need to keep in shape. They look at the drug dealers and see freedom. The drug dealers are aware that the most profound emotion they generate is fear, based on their capacity to back up their power with violence. They look at the soccer stars and see people who are loved for themselves.

None of the players mentioned in this piece have been accused of a crime as a result of this relation. Their explanations appear to have satisfied the police. Of course it is not a crime merely to associate with criminals. Whether it is good for their image is another question -- and it is a question from which, increasingly, there is no hiding place.

Mini cameras, mobile phones that don't only take photos but can also record videos, internet sites which make images available to the public -- all feeding an ever-growing curiosity in celebrities and their lives. Should the big-name player step off the straight and narrow, the chances are that someone will be recording it.

As Ronaldo himself is well aware. A couple of weeks after his visit to Big Brother Brasil he played a poor game, and Corinthians were beaten. After the match he was verbally abused by a fan. He was fat, out of shape, he was robbing the club, and so on. No response.

Then the fan brought up an incident from Ronaldo's past -- when he picked up a prostitute and drove to a motel only to discover that the service supplier in question was in fact a transvestite. In days gone by, he might have got away with it, but in the confusion the transvestite filmed him and placed the images on the internet. No hiding place. It was an international news story, and now, when the angry fan reminded him of the affair, Ronaldo snapped, and responded by giving him the finger.

And that, too, was filmed and became a news story, forming the first serious crack in the relationship between Ronaldo and Corinthians supporters.

The TV show might have ended on Tuesday, but the lesson for Brazil's high-profile soccer players is that Big Brother is still watching you.