There's no escaping sports

Since I withdrew, game-worn, from full-time sportswriting in 2007, the question I've gotten most is: "Do you miss sports?" I wonder if these same people ask retired weathermen if they miss weather, or ex-food critics if they miss food, or recovering nudists if they miss nudity.

Because missing sports is not an option. I couldn't miss them if I tried. And I have tried. But sports, it turns out, are always there. Even when I think they're not, they're present -- silent and odorless and invisible but emphatically present, like radon gas.

Sports were in the pauses on the other end of the phone when I spoke to my Dad in Minnesota one late-summer night while he watched the Twins in his armchair. We had a long conversation punctuated by even longer silences, and only after I hung up in Connecticut did I see on the ticker that the Twins' pitcher was carrying a perfect game into the ninth inning. I called back. "We spoke for a full hour and you never thought to mention that Scott Baker was throwing a perfect game?" I said. And my septuagenarian father, sounding like a chastened child, said in the smallest possible voice: "I didn't want to jinx him."

The composer Claude Debussy said that music is in the silence between the notes. Sports, I've discovered, are like that, too.

Cloistering myself to write a novel, I tried to miss sports, to make them go away. ("Miss it! Miss it!" my conscience told me, impersonating D'Annunzio in Caddyshack.) But even when I didn't know it, I was breathing sports in, like secondhand smoke.

I was inhaling secondhand sports. When one of my brothers had a heart attack on the third hole of a Florida golf course, it had nothing to do with sports, really, until I learned that he had not merely finished out the hole: He had finished out the round, scoring a 91 with what felt like an 800-pound gorilla on his chest. When I asked him why he hadn't gone immediately to the ER for the measures that would save his life, he said, from his hospital bed: "I was sharing a cart."

This is the best illustration I know of Minnesota Nice, the courtesy and self-effacement common to natives of the Gopher State. But it's also testament to the motivational powers of breaking 90. Which my brother would have done, he assures me, if not for "the two bad holes when I was having a heart attack."

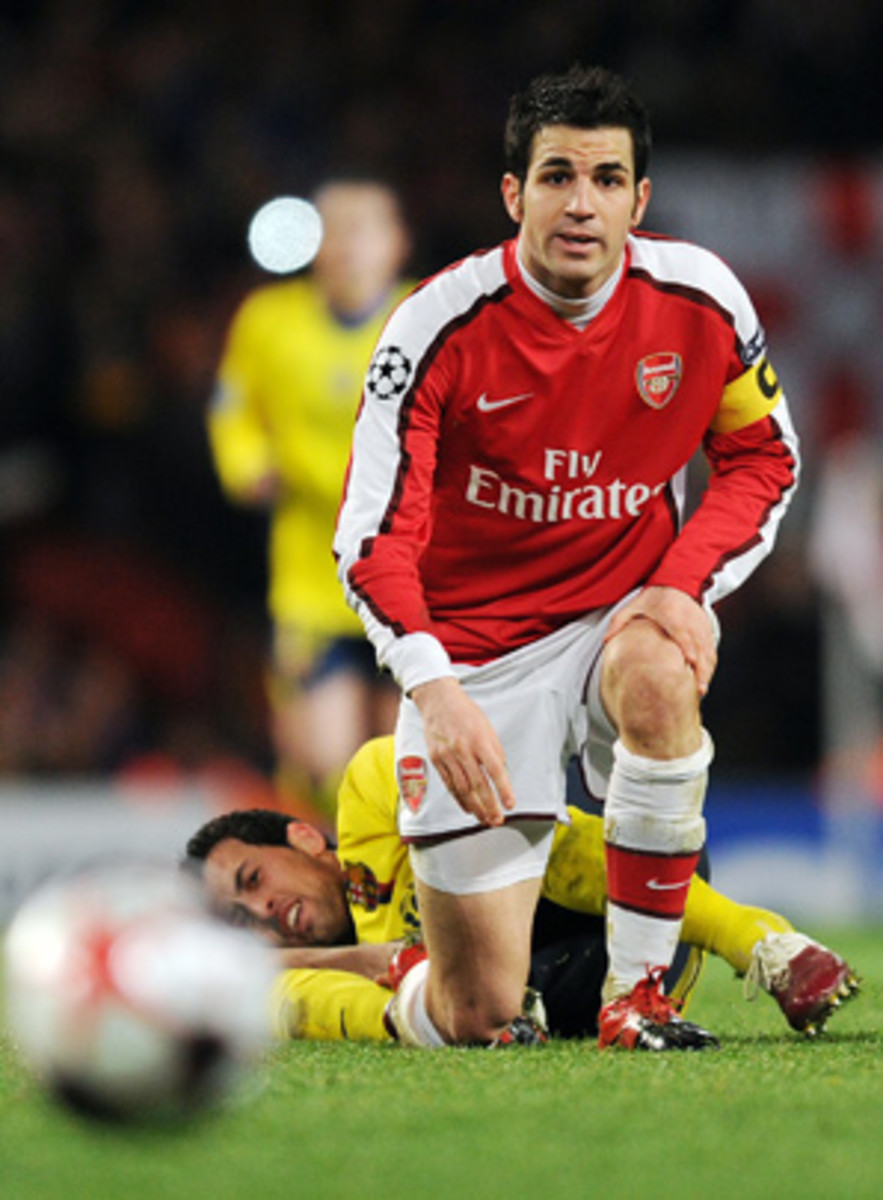

Sports are always there. When I fled the country, sports hunted me down. A short visit to London necessitated a trip to Emirates Stadium, to sit in the locker of Cesc Fabregas, the favorite athlete of my three children and captain of the only sports team they really care about: Arsenal. I sat on the little seat cushion that the Spanish midfielder sits on, hoping his greatness might transfer gluteally to me, and imbue me with reflected glory, for my children have never seen writing as a serious or glamorous profession. "What do you want to be when you grow up?" I asked the five-year-old, and she said after a short interval: "Nothing. Not anything. Because you're not anything, Dad, and I want to be like you."

And so sports have proven unshakeable. Trying to leave sports is like trying to leave the mafia. Only worse, because at least death gets you out of the mafia. Not so with sports. When my Uncle John (Bullet) Burns died in Cincinnati in April, he was buried with his beloved Xavier University basketball tickets in his breast pocket and a can of Cincinnati's finest beer, Hudepohl Delight, at his side. Uncle John wasn't taking any chances on the veracity of the polka title, "In Heaven There is No Beer."

If death gives us no respite from sports, what chance do I have of avoiding them on Earth? In 2008, I attended the wake of Manchester (Conn.) Journal Inquirer sports columnist Randy Smith, and knelt over his open casket to find him accompanied, for all eternity, by his putter. Two years later, I still picture Smith on Cloud 9, having just made a long birdie putt on Cloud 8.

If sports, like death, are inevitable, then I've learned to happily submit, to succumb, to say uncle. Uncle John, to be specific, buried with his hoop tickets, his Hudy Delight and a copy of the Daily Racing Form. When his sweet chariot swung low, comin' for to carry him home, he wanted to know if the horse pulling it liked a fast track, and if it would tire over the final furlong.

In an age when the Internet has given everyone a creative outlet -- even those bereft of a creative inlet -- I'm lucky that sports remain a wellspring, now and apparently forever. There's some comfort in knowing that. When the bony finger of Death taps us on the shoulder, it will be sheathed in the foam finger of Sports, softening the blow.