Odom finds identity with second world championship team

Such is the course of your 24/7 public life when you become a citizen of Kardashian World, as Odom has done with his marriage to Khloe, who is one of the Kardashians, though I know not which.

It all gives rise to the supposition that the man is a little, well, loopy.

Actually, he is.

But it also obscures the fact that Odom is an extremely cerebral and versatile player, a guy who during the NBA season might in one moment be on the perimeter getting the Lakers into their triangle offense and in the next be battling Tim Duncan underneath.

And there is this, too: Only one person in the basketball-playing universe managed to be a "world" champion twice within three months -- Lamar Odom.

Among the several members of the U.S. team who benefited greatly from the gold-medal showing in the FIBA World Championship that ended Sunday in Istanbul -- Russell Westbrook, Andre Iguodala and Rudy Gay come to mind -- Odom got as much out of it as anyone besides, of course, Kevin Durant, whose MVP play put him on a whole other planet. It wasn't about how many pairs of American eyes were watching the action: On Sunday, about 50 times more people watched the Dallas Cowboys-Washington Redskins game than the midday telecast of the U.S.-Turkey final. It was about what the 9-0 championship record meant internally to each player, what it did for his confidence level and his perception of himself as a player.

For we tend to think of pro athletes as finished products, masters of their own domain, supremely confident about their own talents. Certainly many of them act that way, some to the point of delusion. But inside, away from the chest-pounding surety, most are plagued by the same nagging self-doubts as all of us, the same necessity to prove themselves, notch an identity, figure out a way to either become somebody or stay on top just a little longer.

I think that describes Odom, who turns 31 around the 2010-11 season opener. For the first five years of his career (four with the Clippers, one with the Heat), his sackful of talents seduced GMs and coaches into believing that he could be The Guy. Well, he can't be The Guy. It's not Odom. He has spent the last six seasons safely in the shadow of Kobe Bryant and other Lakers teammates, and, while it's comfortable there, more in tune with his complementary game, he has sometimes gotten lost in the L.A. shuffle, his good-but-not-great-at-everything game overlooked in a town built on glitz.

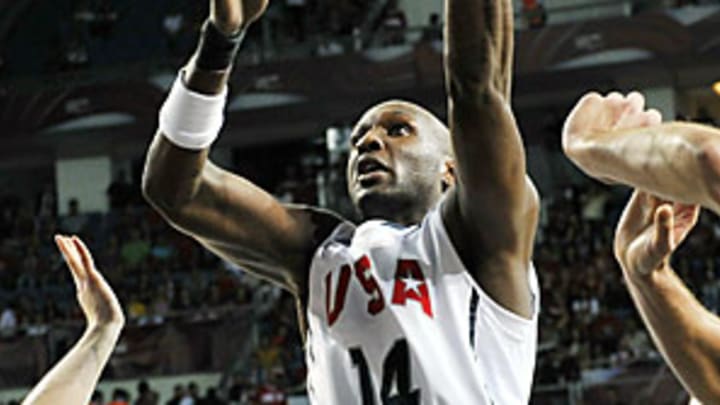

This championship team gave him an identity. He was a leader, a rock, a tough guy and, predictably, a bastion of versatility who averaged 7.1 points (fifth on the team) and 7.7 rebounds (first), while averaging 22 minutes, fourth most behind only Durant, Chauncey Billups and Derrick Rose. He was at his best in the semis and finals against, respectively, Lithuania and Turkey when he registered games of 13 and 10, and 15 and 11.

Even as the U.S. struggled to finalize its roster a month ago, Odom's role was clear: Coach Mike Krzyzewski made him a co-captain and the leader of a defense that never quit. His collar would be blue. He would be asked to station himself near the basket, getting touches from time to time on offense but mostly serving as a defensive stalwart on a team bound to build its identity at that end of the floor. Krzyzewski even used the phrase "relegated Lamar to the post" in acknowledging that Odom was asked to sacrifice his body and a good portion of his offensive stats in the service of this guard-oriented team.

"If Lamar didn't play well for us down there, we don't win," U.S. assistant coach Jim Boeheim said after the victory over Turkey that brought the gold medal. "He rebounds, he rotates, he deflects more balls and helps more than any post player we've ever had. He's a great teammate. Lamar talks. He's fired up. He's done everything we've asked of him."

His backup at center, Tyson Chandler, said that the defensive emphasis didn't just happen.

"Nobody realizes it, but it's harder for an All-Star-type team to come together defensively than offensively," said Chandler, who mostly rode the pine in favor of Odom's experience in the final two U.S. games. "Offensively, you can always run a pick-and-roll or isolate somebody, but defensively you have to have a group that really buys into it and wants it. Coach preached it every day, and Lamar was a big part of that. He's a master at positioning, knowing where to be before the play gets started."

Odom tended to guard bigger players in the man-to-man defense the U.S. played most of the time. He invariably gave up a hoop or two in the beginning of the game, but he would make adjustments as the game went on, wearing them down with smarts and, as Chandler notes, positioning.

"What most people miss about guys like Lamar," said Boeheim, who has coached at Syracuse since 1976 and has never been with an NBA team, "is their ability to make adjustments on the fly. That's what the pro game is all about. These guys make game-to-game adjustments and even minute-to-minute adjustments. Lamar is as good as anyone I've been around in that part of the game."

Still, one could hardly expect a citizen of Kardashian World to be all work, no play, even during a tournament as grueling as the Worlds, and he concedes that "part of the deal in international play is increasing your brand."

And how would he do that?

"Well, you have to understand that the power of networking and meeting the right people is very important," Odom said. "There's no limit on how far you can take that thing. No one ever thought Magic Johnson would become this multimillion-dollar man off the court, right? Who's to say who you're going to meet at dinner over here, right? Maybe a sultan."

I asked Odom if that happened.

"I wouldn't tell you if it did," he answered.

If it did, I'm sure the Keeping Up With the Kardashians cameras were rolling and we'll see it down the road.

Special Contributor, Sports Illustrated As a member of the Basketball Hall of Fame, it seems obvious what Jack McCallum would choose as his favorite sport to cover. "You would think it would be pro basketball," says McCallum, a Sports Illustrated special contributor, "but it would be anything where I'm the only reporter there because all the stuff you gather is your own." For three decades McCallum's rollicking prose has entertained SI readers. He joined Sports Illustrated in 1981 and famously chronicled the Celtics-Lakers battles of 1980s. McCallum returned to the NBA beat for the 2001-02 season, having covered the league for eight years in the Bird-Magic heydays. He has edited the weekly Scorecard section of the magazine, written frequently for the Swimsuit Issue and commemorative division and is currently a contributor to SI.com. McCallum cited a series of pieces about a 1989 summer vacation he took with his family as his most memorable SI assignment. "A paid summer va-kay? Of course it's my favorite," says McCallum. In 2008, McCallum profiled Special Olympics founder Eunice Shriver, winner of SI's first Sportsman of the Year Legacy Award. McCallum has written 10 books, including Dream Team, which spent six seeks on the New York Times best-seller list in 2012, and his 2007 novel, Foul Lines, about pro basketball (with SI colleague Jon Wertheim). His book about his experience with cancer, The Prostate Monologues, came out in September 2013, and his 2007 book, Seven Seconds or Less: My Season on the Bench with the Runnin' and Gunnin' Phoenix Suns, was a best-selling behind-the-scenes account of the Suns' 2005-06 season. He has also written scripts for various SI Sportsman of the Year shows, "pontificated on so many TV shows about pro hoops that I have my own IMDB entry," and teaches college journalism. In September 2005, McCallum was presented with the Curt Gowdy Award, given annually by the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame for outstanding basketball writing. McCallum was previously awarded the National Women Sports Foundation Media Award. Before Sports Illustrated, McCallum worked at four newspapers, including the Baltimore News-American, where he covered the Baltimore Colts in 1980. He received a B.A. in English from Muhlenberg College in Allentown, Pa. and holds an M.A. in English Literature from Lehigh University. He and his wife, Donna, reside in Bethlehem, Pa., and have two adult sons, Jamie and Chris.