The most important three-week period in sports history

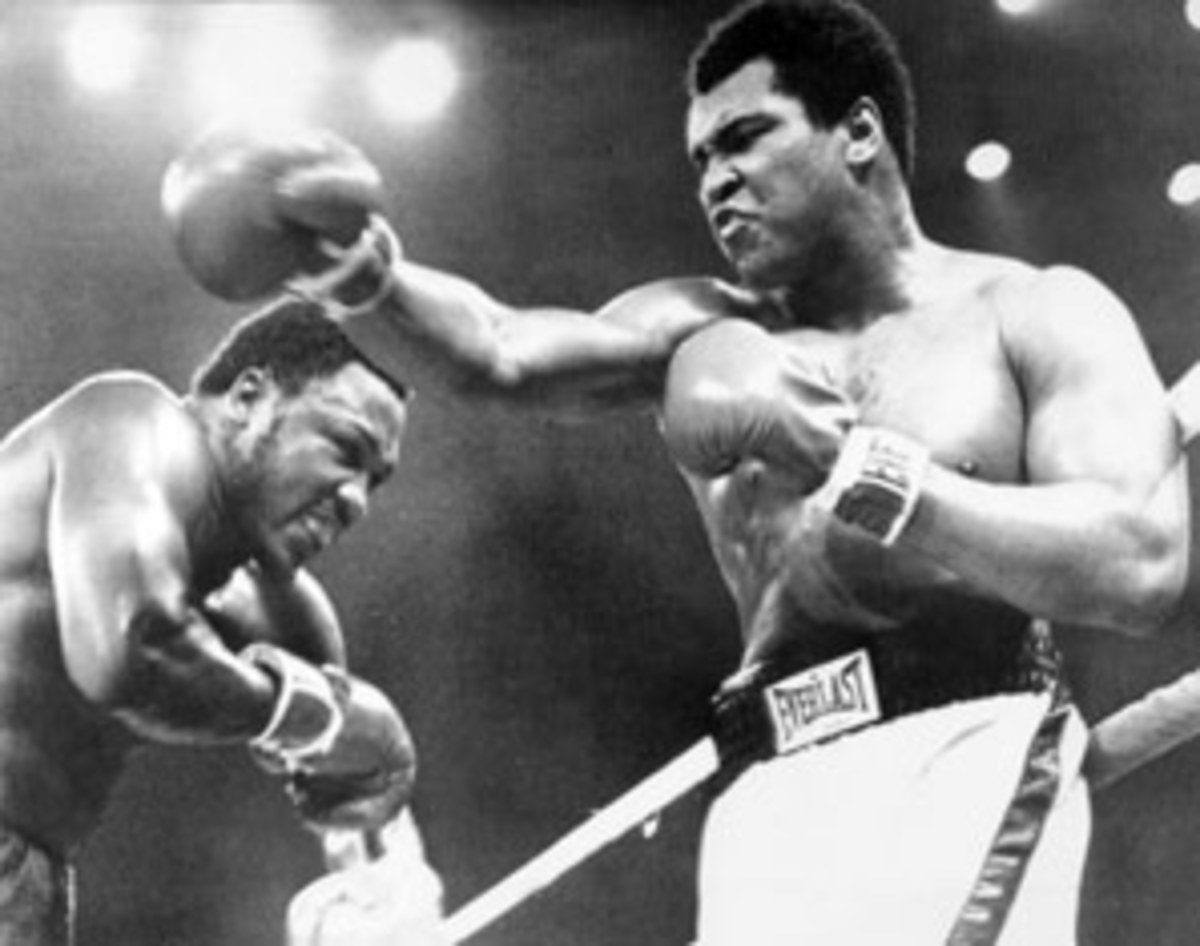

The weeks in question were rung in, literally, at 10:45 a.m. local time on Oct. 1, in Quezon City in the Philippines when a bell opened the third heavyweight title fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Ask not for whom that bell tolled, boxing. It tolled for thee.

By the time the Thrilla in Manila was over, after 14 epic rounds, so was a glorious era of sports, in which heavyweight boxing was bigger than anything, a globetrotting carnival that commanded the world's attention, luring legions of press almost anywhere. A year earlier, Ali had fought George Foreman in Zaire. The fight in the Philippines was almost contested in Cairo.

Unlike most Super Bowls, Ali-Frazier III proved worthy of Roman-numeral bravado and "world champion" hyperbole. But the greatest heavyweight fight of all time left the sport with nowhere to go but down. And boxing, as ever, obliged. Never again would there be a heavyweight rivalry as compelling. Never again would the most famous man in the world be a prizefighter. The sports landscape was changing. Its riches were being redistributed.

Six days after the fight in the Philippines, on Oct. 7 -- the day the Reds swept the Pirates to advance to the World Series -- the Major League Baseball Players Association filed a lawsuit on behalf of pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally. Messersmith won 20 games for the Dodgers in 1974 and had the audacity, afterward, to request a no-trade clause in his contract. Owner Walter O'Malley refused and Messersmith, behind union boss Marvin Miller, challenged the reserve system that bound a player to his team in perpetuity. Six years earlier to the day, on Oct. 7, 1969, Curt Flood was traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies, prompting him, unsuccessfully, to challenge the reserve clause.

This time around, of course, the players would win. Messieurs Miller, Messersmith and McNally would help usher in -- six days after boxing was ushered out -- the modern era of professional sports, with all its Messersmithian messiness. Free agency made the games more just and more mercenary, wildly rich and ever in danger of devouring themselves. For athletes, from that day forward, the stakes would only get higher.

Indeed, five days after the Messersmith suit was filed -- on Oct. 12, 1975 -- Marion Jones was born in Los Angeles. Two days later, Floyd Landis was born in Farmersville, Pa.

Both Jones and Landis would become world-class athletes, winning the most prestigious competitions in their respective disciplines. Track star Jones, the five-time Olympic medalist, and cyclist Landis, winner of the 2006 Tour de France, came to physical maturity in the mid-1990s, when steroids were upping the competitive ante in many sports. Both athletes would be stripped of their honors after testing positive for performance-enhancing drugs. Both would deny -- then admit to -- having cheated. And so the two athletes, born two days apart, would become twinned again, this time as emblems of an era.

But only in hindsight. Thirty-five years ago, Americans weren't thinking of PEDs. They were very much thinking of Reds. The World Series between the Reds and Red Sox opened on Saturday, Oct. 11, 1975. It was an eventful day. Oklahoma beat Texas 24-17 to keep its national title hopes alive in football. Young lovebirds Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham were married in Fayetteville, Ark., in a ceremony that would have profound implications on future news cycles. (Liz Taylor and Richard Burton, dominators of previous news cycles, were also married that day, for the second time.)

That night, Ali's television sidekick, Howard Cosell, hosted a show on ABC called Saturday Night Live, featuring, among others, Joe Frazier and Joe Namath. Debuting the same night was a show called NBC's Saturday Night, which wouldn't take the name Saturday Night Live until Cosell's show was canceled.

But what transfixed America that Saturday was Game 1 between the Reds and Red Sox, whose respective aces, Don Gullet and Luis Tiant, took dueling shutouts into the bottom of the 7th, setting the table for an exceedingly compelling Fall Classic. The series was headed for late autumn. Baseball itself was already there, metaphorically, its cultural dominance waning in a blaze of color.

Delayed by three days of rain, the series wouldn't get to its famous Game 6 until Oct. 21. But by the time Sox catcher Carlton Fisk was waving fair his 12th-inning, hop-off home run, it was 12:34 a.m. on Oct. 22: Three weeks to the day after the Thrilla in Manila, and the very same day that the Reds and Sox would contest Game 7 of the Series.

No sport would have a better 24 hours than baseball had then. More than 70 million Americans would watch the Red wins Game 7, putting it in the company of Super Bowl IX as the two most watched sporting events in U.S. history at the time.

Understandably, few people noticed what else happened that afternoon, between the end of Game 6 and the start of Game 7: Owners in the upstart World Football League quietly voted to disband. Unable to challenge the NFL's hegemony, the league simply gave up.

The decision proved prescient. Thirty-five autumns later, the NFL looks invulnerable; free agents and confessed performance-enhancers will play critical roles in baseball's postseason; another Clinton wedding has recently released its grip on the national news cycle -- and few Americans could tell you, under penalty of death, which Klitschko brother is heavyweight champion of which boxing organization.