The role of race in sports movies

A few weeks back, the New York Times ran an insightful piece about the absence of black nominees at the Oscars this year. Among the ten Best Picture nominees, not a single one has a major black character. Particularly with The Fighter in the ring contending for Best Picture -- and with even odds-on favorite The King's Speech following a crowd-pleasing underdog-finds-unconventional-coach-and-surmounts-adversity formula -- it's probably as good a time as any to discuss the role of race in sports movies.

The Fighter is a prime example of the triumph of the white underdog, a theme that rings through most sports pictures. The Rookie, Seabiscuit, Miracle, Million Dollar Baby, Cinderella Man, Invincible, The Greatest Game Ever Played, Secretariat, even the ABA comedy Semi-Pro -- they all revolve around white folks beating the odds to make the team, win the big game, big fight or big race.

Especially given both the demographics and prominence of African-Americans in the Republic of Sport, you'd be within your rights to ask: Where are the people of color in these movies? Sure, there are some black athletes rendered on the big screen. Glory Road, The Express, Ali, to name three. But much more likely: when black characters show up in sports movies it's not as the hero/athlete -- never mind the coach or executive -- but rather as the mystical, and mystifying, All-Knowing Black Guy (AKBG).

Who's that, you ask? You actually know him well. He's become a stock character in sports movies, the font of wisdom who's typically a subordinate but able to see what the protagonist cannot. He may be a drifter, or destitute, or disabled, usually residing on society's margins. He has his limitation (and thus knows his place?), yet our hero desperately needs his help. Luckily, the AKBG is there to serve.

Morgan Freeman has, of course, made a career of playing this role, the omniscient narrator who possesses both wisdom and clairvoyance -- his half-blind janitor/trainer Scrap in Million Dollar Baby being one example. But, really, name a sports movie and odds are good the AKBG figures in the (all but inevitably happy) ending. It's Will Smith as mystic-drifter-caddy Bagger Vance explaining to Matt Damon, that he "can't see that flag as some dragon you got to slay. You got to look with soft eyes. See the place where the tides and the seasons and the turnin' of the Earth, all come together."

It's Fortune the stadium janitor (Charles S. Dutton) telling Rudy to stop with the self-pity about failing to make the Notre Dame football team and instead recognize how lucky he is simply to be getting a college education. It's Chubbs -- also disabled, also a caddy -- telling Happy Gilmore that golf is little different from hockey, requiring only talent and self-discipline.

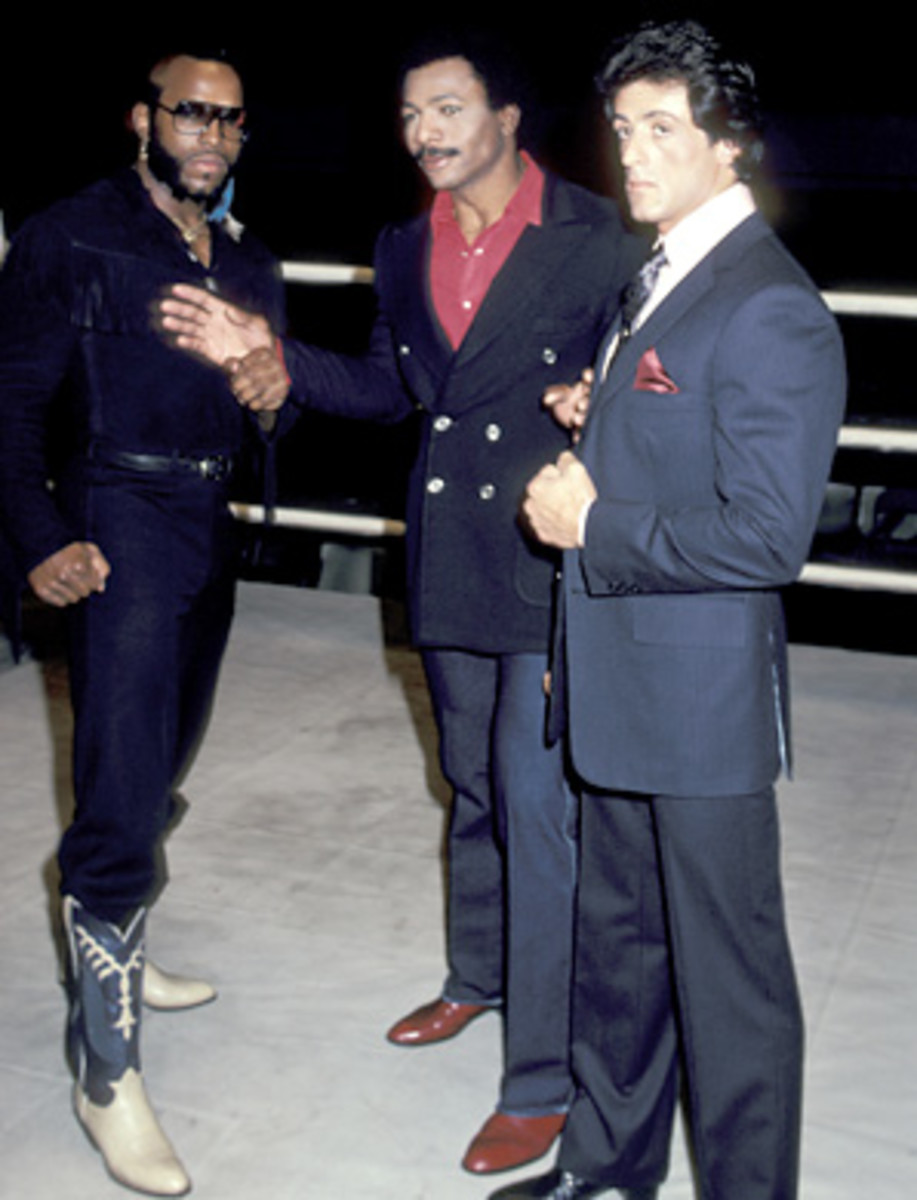

Chubbs is played by Carl Weathers, who did a previous turn as the AKBG in Rocky III, returning to train and inspire the Italian Stallion. It's not entirely clear why Apollo Creed would be motivated to impart wisdom to the man who ended his career. (And we won't even begin to try to dissect Apollo's bizarre request at the movie's conclusion to fight his new friend/boss behind closed doors). Yet there he is, the AKBG kicking wisdom about the "Eye of the tiger," sagely explaining that "There IS no tomorrow," exhorting Rocky to victory as they race on the beach in short-shorts, joyfully embracing in the ocean foam when Rocky finally breaks the tape.

Perhaps the best recent example of the sports movie All-Knowing Black Guy is Eddie Sweat (Nelsan Ellis) in Secretariat. Sweat is an endearing groom who sleeps in the stables and is said to "hear the horses' thoughts through his hands." As dawn breaks before the Kentucky Derby, it is Eddie who perspicaciously tells the audience: "You 'bout to see somethin' you ain't never seen before!"

What's up with these unlikely muses, so far down on the societal org chart, giving inspiration to the protagonists? At a minimum, the AKBG present a device through which the movie can offer a potential history lesson. But even there, the filmmakers let the opportunity slip by and, well. Pull punches. In Happy Gilmore, Chubb explains that in the 1960s he was primed to become "the next Arnold Palmer."

"What happened?" wonders Happy.

"I wasn't allowed to play pro anymore."

"Because you're black?"

And here we arrive at -- to use the voguish phrase -- a teachable moment, a chance to address segregation and the evils of exclusionary clubs.

"Hell, no," says Chubb. "An alligator bit my hand off!"

If this trope sounds familiar, well, it is. In The Sandlot, James Earl Jones plays the role of Mr. Mertle, a former pro baseball player, now blind and living modestly. The kids stay the hell away from Mr. Mertle, mostly because of his intimidating dog, The Beast. In the third act, the kids arrive at his house desperately hoping to retrieve the baseball signed by Babe Ruth that The Beast had taken. Mertle surprises the kids, first with his gentle manner and then by handing over a ball signed by the entire 1927 Yankees team. Mertle explains that he was a contemporary of "George" (Babe Ruth) and shows a picture of himself in a Pittsburgh uniform. "He was almost as great a hitter as I was," Mertle tells the kids. "I would've broken his records, but ..."

Again, despite crafting an opening to discuss baseball's color line, the movie offers a much less tendentious reason for Mertle's disappointment; he crowded the plate, got hit by a pitch and went blind.

That photo we see of Mertle in a Pittsburgh uniform, posed alongside Ruth? Presumably, it's when he played for the Crawfords of the Negro Leagues and Ruth passed through on a barnstorming tour. But how is The Sandlot target audience -- boys, ages, say, 8-16 -- ever to infer that? They're not. It's as if the filmmakers are drawn to the fascinating-but-uncomfortable realities of our racial history but at the last minute lose their nerve and back off the plate, as it were.

It's no doubt true that from a less racially-specific perspective, the AKBG is simply part of a time-tested Hollywood conceit: create some misdirection, defy some superficial expectations. It's the same reason why the salt-of-earth midwesterners invariably know the truths and life lessons that elude the ambitious, slick pedigreed elites from either coast. (We await the movie in which the investment banker travels to the Ozarks and imparts his worldliness and mastery of financial markets on the naive locals.)

But, again, the unsettling question: Why are these sports movie AKBGs always so marginalized and secondary, and so very focused on the success of the hero? To be charitable, one could argue that the wisdom of these frequently beaten-down, disabled AKBGs is a testament to the (mostly unconvincing) notion that a hard-knocks life is the best teacher. According to that logic there are actually benefits derived from being trapped in poverty, disabled, beset by discrimination -- a view that might comfort the (mostly) white filmmakers who put out these movies and the (mostly) white audiences who consume them. More cynically, could it be that without one form of life disability or another, the AKBG might be too capable, too formidable for the white-centric narrative and the anxious white imagination?

Perhaps, in the end, one of these sports movie All-Knowing Black Guys again knows best. As Chubbs says to Happy Gilmore as he snuggles behind the hero and offers him a swing tip, "It's just easin' the tension, baby."