Killebrew ahead of his time

Harmon Killebrew, who passed away Tuesday morning at the age of 74 after a battle with esophageal cancer, was one of the greatest home run hitters in baseball history, a fact that has been somewhat obscured by the power surge of the last two decades. Before Mark McGwire passed him in 2001, Killebrew ranked fifth all-time with 573 career home runs, and of the four players ahead of him at that time, only Babe Ruth had homered more often than Killebrew's once every 17.2 plate appearances. McGwire was the first of six players to pass Killebrew's career total in the last decade, but Killebrew's eight 40-homer seasons, a total since tied by Hank Aaron, Barry Bonds, and Alex Rodriguez, remain second only to Ruth's 11.

What made Killebrew's clouts all the more impressive were both the tremendous height and distance of their flight paths and the period in which he hit most of them, the pitching-dominated 1960s. From 1963 to 1968, the last six years before the mound was lowered and a time in which the strike zone was defined as extending from a batter's knees to his shoulders (it currently tops out at the middle of the chest, and those strikes are rarely called), Killebrew and Willie Mays led all of major league baseball with 219 home runs. What's more, Killebrew suffered major injuries in two of those seasons, losing 48 games to a separated elbow in 1965 and 66 games to a leg injury in 1968, and had 226 fewer plate appearances than Mays during that span. Over the course of that entire decade, Killebrew led all players, out-homering Hank Aaron 393 to 375 in 619 fewer plate appearances.

When the mound was lowered in 1969, Killebrew, who had worked extra hard that winter in an attempt to come back from his injury in '68, had his finest season, leading the majors with 49 home runs and 140 RBIs, the American League in walks (145, 20 of which were intentional) and on-base percentage (.427), and taking home the AL Most Valuable Player award while leading the Twins to the first of two consecutive division titles in the newly-created American League West. Killebrew received MVP votes in 11 different seasons, finished in the top four six times and made 11 All-Star teams.

Killebrew spent 21 of his 22 seasons with a single team (the original Senators, who moved to Minnesota in 1961), played on three first-place clubs, including the 1965 pennant winners that pushed the Dodgers of Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale to seven games in that year's World Series, and was widely regarded as one of the nicest men in the game, but he wasn't elected to the Hall of Fame until 1984, his fourth year on the ballot. That last likely had to do with his .256 career batting average and poor defensive reputation, evidenced by his continued movement around the diamond, from third base to first base, to leftfield, and back around.

Indeed, Killebrew was in effect a designated hitter before the position was invented, and a player whose value at the plate was largely tied up in home runs and walks. In that way, he was ahead of his time. The last couple of decades have given birth to a plethora of so-called Three True Outcome players, players who see roughly 40 percent or more of their plate appearances end in a home run, walk, or strikeout (known as the three "true" outcomes because they don't involve the vagaries of fielding). Killebrew, who averaged 38 home runs, 104 walks, and 113 strikeouts per 162 games over the course of his career, saw 39 percent of his plate appearances end in one of those three outcomes. Among players with 4,000 or more plate appearances to begin their careers prior to 1967, only Mickey Mantle (40.2) had a higher Three True Outcome percentage. Now, Killebrew doesn't even crack the top 20.

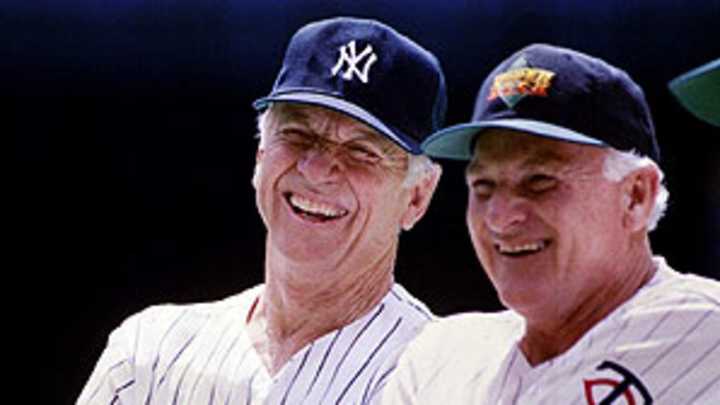

For younger generations, the best way to understand Killebrew is to think of Jim Thome, a comparison that seems to be inescapable now that Thome, one of the six men to pass Killebrew on the all-time home run list, plays outdoor baseball in Minneapolis with a Twin-Cities logo on his cap. Both the Idaho-born Killebrew and Illinois-born Thome belied their gentle, Midwestern demeanor with raw, Bunyonesque strength. Both came up as third baseman and later moved across the diamond to first. Both hit for modest averages while specializing in the three true outcomes (Thome, a career .277 hitter, has produced one of the three in a whopping 47.6 percent of his plate appearances).

The biggest difference between the two on the field, beyond the facts that Thome bats lefty and Killer hit righty and that Thome is a fair bit larger than the 5-foot-11, 210-pound Killebrew was, is when they played. The last two decades have produced a bounty of similarly skilled and similarly productive first basemen, a product of the offensive explosion of those decades (whatever you attribute it to, from small ballparks to expansion pitching to performance enhancing drugs, which Thome has never been associated with) and an increased appreciation for such Three True Outcome hitters. In Killebrew's day, strikeouts were anathema, walks didn't appear on the backs of baseball cards, and hitters were judged by their batting average above all else. As Rogers Hornsby famously declared during Roger Maris's pursuit of the single-season home run record in 1961, "It would be a disappointment if Ruths' record were bested by a .270 hitter." Killebrew finished tied for third in the AL in home runs that season, behind Mantle and Maris, with 46. He hit .288.

The 1961 season was Killebrew's first in Minneapolis's relatively hitting-friendly Metropolitan Stadium, but Killer didn't need the help. In his career, he hit just nine more home runs at home than on the road. In his two full seasons playing for the Senators in Washington, DC's cavernous Griffith Stadium (it was 350 feet down the left field line and 380 feet to the left field gap during those two seasons), he hit 72 home runs, 34 of them coming at home, including an AL-leading 42 in 1959 (a season in which he hit .242).

Though it has been obscured by recent history, that is Killebrew's legacy as a player: the home run. Few hit as many, as far, or as often as he did. More than that, however, he was one of the game's true gentleman, and a man before his time in his understanding of the value of getting on base and loading up for the longball. That last goes back to a spring training conversation the teenaged Bonus Baby Killebrew had with Ralph Kiner, one of the few men of his era to go deep more often than he did. As Killebrew recounted for former commissioner Fay Vincent in his oral history We Would Have Played for Free just a few years ago, he started his career as a high-average hitter who would spray the ball all over the field, but Kiner told him that if he moved up on the plate and tried to pull the ball more, he could hit for power more consistently. Using the simple logic that "home runs do drive in runs," Killebrew took Kiner's advice and the most prolific home run hitter of the 1960s was born.

Cliff Corcoran is a contributing writer for SI.com. He has also edited or contributed chapters to 13 books about baseball, including seven Baseball Prospectus annuals.