Special Report: Scandal. Shame. A search for answers at Penn State.

Too small to be considered a full-fledged town, the borough of Mill Hall, Pa., abuts a winding creek in the shadow of the Allegheny Mountains. Most of the 1,500 or so residents work nearby and cheer for Penn State. That includes Steven Turchetta, the athletic director and until recently the football coach at Central Mountain High. Turchetta, known around Mill Hall as Chet, carries himself with the easy grace of a former jock, and he was excited to coach his Wildcats team alongside Jerry Sandusky.

A defensive coach at Penn State for 32 years, including 23 as coordinator, Sandusky was a revered figure, responsible for the program's Linebacker U reputation and at one point the man in line to succeed Joe Paterno -- if and when JoePa ever retired. But in 1999, Paterno told Sandusky he would not, in fact, be the next head coach, and Sandusky abruptly announced that he would retire after the '99 season at 55. Though at an age when many coaches are still in their prime, Sandusky never returned to the college sideline, instead working full time at The Second Mile, a charity for at-risk children that he founded in '77. In 2002, Sandusky began volunteering at Central Mountain High, working with players and sitting in the booth during games. By '08 he was a full-time volunteer.

Turchetta had noticed, though, that something was amiss. Sandusky would get into shouting matches with Central Mountain students, and Turchetta would have to defuse the conflicts. He also found Sandusky to be "clingy" and "suspicious" with one freshman boy in particular. Sandusky sometimes came to the school and pulled the student out of class to meet with him privately.

In 2009, the boy's mother made a troubling report to the school. When he was 11 or 12, her son had met Sandusky through The Second Mile, which had grown into a nationally renowned nonprofit with assets of close to $9 million. Now, several years later, the mother became suspicious when her son asked her about "sex weirdos." She notified the school, and the principal brought the student into the office to discuss the situation, whereupon the boy told the principal that Sandusky had been sexually assaulting him. After the school informed the mother, she notified the local child protective services agency, which launched an investigation into Sandusky. Central Mountain officials promptly barred him from the school. When asked under oath about Sandusky's behavior in the years leading up to the victim's 2009 revelation, Turchetta provided unsparing and unambiguous answers.

Joe Miller is a Penn State fan too -- if not to the extent of his father, who on fall Saturdays was a 50-yard-line usher at Nittany Lions home games. A worker at the local paper factory, Miller, 44, has served as a wrestling coach in Mill Hall. Like Turchetta, he was aware of Sandusky's glowing career at Penn State and thought even more highly of his charitable work. Every year Miller and his wife, a school guidance counselor, contributed to The Second Mile. Miller, though, had once seen Sandusky lying on a weight room floor, face-to-face with the boy in question, with his eyes closed. Miller, too, when asked by investigators about what he'd seen, gave a precise and independent account.

Both Turchetta and Miller knew Jerry Sandusky. At some level they knew what their testimony could mean for his reputation. What they could not possibly have known was that their accounts would help set in motion the most explosive scandal in the history of college sports, one that would make a mockery of the recent drumbeat of NCAA outrages. Rogue boosters? Players selling jerseys for tattoos? Heisman-caliber quarterbacks available for purchase? By the end of last week those transgressions seemed quaint.

Once notified of the events in Mill Hall, a combination of Pennsylvania legal and child welfare agencies began a multiyear investigation into Sandusky and his conduct with boys as young as 10 years old. On Nov. 4, Pennsylvania attorney general Linda Kelly and State Police Commissioner Frank Noonan filed a grand jury report that depicted the 67-year-old Sandusky -- in 23 pages of stomach-twisting detail -- as the embodiment of unadulterated evil, a coldly manipulative serial sexual predator. Often through the access he gained by way of The Second Mile, the report alleges, Sandusky first built trust and relationships with young boys -- vulnerable, socially at-risk kids from his own foundation -- then sexually assaulted them. The report alleges that between 1994 and 2009, Sandusky abused eight boys, though a source tells SI that multiple others have consulted lawyers.

The report asserts that Sandusky traded on his status as a Penn State football demigod. Many of the alleged assaults occurred either in the university's football facilities or at football functions. The Nittany Lions program became Sandusky's bait. He brought victims to games at State College, allowed them to attend coaches' meetings, facilitated their meeting players, cast them in instructional videos, and in one case took a boy to the Alamo Bowl, in San Antonio. Sandusky was charged with 40 counts of various sex crimes, seven of them involuntary deviate sexual intercourse, a felony. In an interview with NBC on Monday, his first public statement, Sandusky admitted that he "horsed around" and showered with boys but denied the criminal allegations.

In addition to the charges against Sandusky, Penn State's athletic director, Tim Curley, 57, was charged with perjury and failure to report Sandusky's alleged child abuse in a 2002 incident. So was Gary Schultz, 62, who as Penn State's senior vice president for finance and business oversaw the campus police. While Paterno wasn't charged, his testimony is recounted in the grand jury report. After its release Paterno was widely condemned by the public -- and, implicitly, by law enforcement -- for what appeared to be, at best, galling obliviousness. "I don't think I've ever been associated with a case where that type of eyewitness identification of sex acts [took] place where the police weren't called," Noonan told reporters, echoing the speculation already expressed by so many others that Penn State administrators had covered up Sandusky's crimes to protect the image of the university. "I don't think I've ever seen something like this before."

*****

Within hours of the report's release, the scandal began metastasizing. By the following Monday, Curley had taken administrative leave and Schultz had resigned. As a media swarm descended on State College, every tin-eared statement by a Penn State official accelerated the crisis. On Wednesday, Graham Spanier, the school's president since 1995, was fired for his actions and inactions in the Sandusky matter. Asked whether Spanier might face indictment as well, Kelly responded, "It's an ongoing investigation."

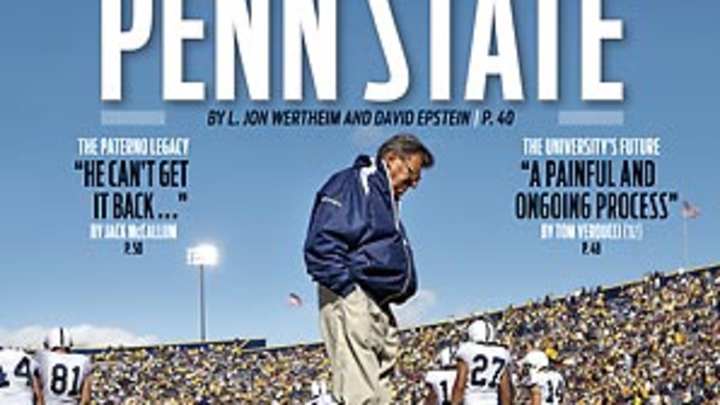

Momentous as those abrupt moves may have been, they were rendered mere footnotes on Wednesday night when the Penn State Board of Trustees announced that it had fired not only Spanier but also Joe Paterno. The notion was, in some ways, unfathomable. Here was the most successful coach in the history of college football -- arguably the most unfireable person in all of sports -- gone, and not of his own volition. What's more, the man known as much for his moral authority as for his record 409 wins was being shown the door over an ethical failure that even he conceded was a horrible lapse in judgment. "It is one of the great sorrows of my life," Paterno said in a written statement earlier in the day. "I wish I had done more."

Doing more at the time would have brought a raft of bad publicity; having done less will leave an ineradicable stain. "Penn State will never fully get its reputation back as the guys in the white hats," says Charles Yesalis, a retired Penn State health policy and sports science professor. "Part of that was smoke and mirrors." Adds Mary Gage, former director of the undergraduate fellowships office at Penn State, "It's amazing to think what one man can do to a whole heroic institution if the reaction is faulty."

*****

For most of his more than six decades at Penn State, Joe Paterno would walk to work from his four-bedroom house on the fringe of campus, the kind of gesture -- an authentic, unpretentious throwback -- that endeared him to so many in Happy Valley and beyond. But the walk also afforded Paterno the opportunity to survey his empire. His home may have been astonishingly modest (current estimate: $415,000) for a man of his stature, but his regal trappings festooned the campus. There is the library that bears his name; the campus creamery that famously scoops Peachy Paterno ice cream; the health center he helped endow; assorted statues and murals; and the Lasch football facility, a fortress underwritten by friends of Paterno. He is even on the syllabus, COMM 497G -- Joe Paterno: Communication & the Media. JoePa Class, the students called it.

That nickname, JoePa, while a play on words, also connoted a fatherly presence. His role in elevating Penn State's profile and its endowment -- which barely existed when he began and now nears $2-billion -- cannot be exaggerated. One story among many: Several years ago Paterno scoffed when he was asked to do a national Burger King commercial, only to reverse course when he realized how much money he could donate to the library from the royalties. Even those ambivalent toward Paterno appreciate his unmistakable contribution to the school. "There's an emphasis on athletics that necessarily results in a de-emphasis on everything else," says Penn State journalism professor Russell Frank. "But a lot of us owe our jobs to him, in a sense. He grew the university so much, and that's attributable to how high-profile the football program has been."

Outgoing, accessible (his home phone number is in the campus directory) and philanthropic, Paterno was the benevolent despot. But he was a despot nonetheless. Org chart be damned -- unlike Schultz and Curley, Paterno is not classified as a senior staff member -- he ran the place. "He built this university, he built this town, and everybody knows it," says longtime State College resident Mark Brennan, a journalist who chronicles Penn State athletics. In 2004, Curley and Spanier visited Paterno at his home to suggest that, at age 77 and after a 3-9 season in '03, he should retire. Paterno, in effect, told them to get off his lawn. They acceded. He went on to coach eight more years. There were less dramatic if more literal examples too. Cindy Way, a Penn State alum who lives in town, once took a shortcut across the grass near the on-campus skating rink. Paterno jumped out of his car and told her to take the sidewalk. "It was," she says, "like being scolded by God."

As his program ascended, so much about the school seemed to cast itself in Paterno's image. The team's nameless jerseys and unadorned white helmets reflected the hidebound coach. Like JoePa, an English major at Brown who became a successful football coach, Penn State, a regional agricultural school, became a premier research institution with a football program courted by the Big Ten. The school thinks of itself as a striver that reached the grand stage, fiercely independent and unapologetic, celebrating old-fashioned mores. (To wit: an on-campus creamery.) Paterno's self-styled morality -- Success with Honor was his trusted motto -- was absorbed by osmosis on the campus, creating a certain high-mindedness that sometimes bled into righteousness. The school's rallying cry -- "We are Penn State!" -- implies that no further explanation is needed. We get it. You don't.

Their domain is Happy Valley, and while it's the Happy that's stressed, the Valley is significant too. For a prominent university, Penn State is remarkably isolated, nestled in the hinterlands of Pennsylvania, six hours from the nearest conference rival and three hours from a major city. (As many learned last week, the impenetrability is heightened by a status that exempts PSU from meaningful state open-records laws. Many documents related to the Sandusky case, such as e-mails between university officials, are not subject to public disclosure.) Like Russian nesting dolls, there are levels of isolation within Penn State, the innermost of which is the football team, which has separate facilities from the rest of the athletic programs and a lavish training facility all its own.

Such insularity has worked to the benefit of the team's image. While the Nittany Lions eagerly trumpeted to recruits that they had never faced serious NCAA scrutiny or sanction, it has hardly been a spotless program. Three years ago ESPN reported that between 2002 and '08, 46 players had been charged with a total of 163 crimes ranging from public urination to murder. In March, SI published arrest tallies for all the programs in its Top 25. Penn State tied for fourth, with 16 players on the '10 opening-game roster who had been charged with a crime. Last week Harrisburg's Patriot-News, which broke the story of the Sandusky investigation in March, made passing reference to "a player-related knife fight in a campus dining hall" that was broken up by assistant coach Mike McQueary in '08.

In 2005, defensive end LaVon Chisley was quietly kicked off the team for academic reasons and, according to prosecutors, began racking up debts. He was never drafted, and that summer he murdered his former roommate, a campus marijuana dealer. Chisley is serving a life sentence. Yet when asked about the incident at a press conference after the conviction, Paterno brushed it aside: "I have no comment on that. ... Why should I?" And when ESPN questioned Paterno about the spate of player arrests, he responded, "I don't know anything about it." In 2003, after Tony Johnson, a wide receiver and the son of a Penn State assistant coach, was arrested for DUI, Paterno complained that "it will get all blown out of proportion because he's a football player. But he didn't do anything to anybody." While the coach apologized for that last remark, the image of Penn State as a haven of virtue -- at least by the limbo-bar standards of big-time college football -- persisted.

Karen G. Muir, a State College attorney who has represented Penn State football players in legal trouble, says she has seen firsthand how the team will sacrifice an individual for the sake of the program. After Penn State defensive tackle Chris Baker, later an NFL player, was involved in two off-field fights, Muir says she planned to go to trial to defend him from criminal charges, yet coaches prevailed on her client to take a plea bargain, thus sparing the program protracted embarrassment. "My experience is that Penn State football closes ranks and their focus is on the program as opposed to the individual," Muir says. "The program didn't care as much what was best for my kid."

The Sandusky grand jury report strongly suggests a similar desire to keep things quick and quiet. The first allegation against Sandusky stems from a 1998 incident in which he allegedly bear-hugged an 11 year old boy in the shower at the football facility. When the boy came home with his hair wet, his mother contacted university police, and an investigation was launched. Police listened in to discussions between the mother and Sandusky in which Sandusky apologized and admitted, "I was wrong. ... I wish I were dead." Yet shortly thereafter the case was closed. No charges were filed.

In an eerie twist, the local prosecutor at the time, Ray Gricar, disappeared in 2005. His laptop and hard drive were recovered from the Susquehanna River, irretrievably damaged, and his body was never found. It made for hot conspiracy theories last week. Contacted by SI, Tony Gricar, Ray's nephew and the family's spokesman, would not dismiss anything out of hand. He said that while his uncle was indifferent to the football program, he knew he would need an airtight case. "There [were] far-reaching consequences for Ray bringing a case against Sandusky," Tony Gricar said. Borrowing a line from The Wire, he added, "You come at the king, you best not miss."

Sandusky retired following the 1999 season, asserting that he wanted to devote his full energy to The Second Mile. But as part of his retirement package, he was conferred emeritus status, with full access to the Penn State football facilities, including an office and a phone. According to the grand jury report, in the fall of 2000, a Penn State janitor saw Sandusky in the football showers performing oral sex on a boy. The janitor was so upset he was moved to tears, and co-workers feared he might have a heart attack. They also feared for their jobs. (The report notes that after the alleged incident, Sandusky was seen driving slowly through the parking lot on two different occasions that night.) No report was ever filed; the witness now suffers from dementia and was incompetent to testify before the grand jury.

The charge that has generated the most discussion, and that led directly to the firing of Spanier and Paterno, stems from a 2002 incident. McQueary testified that on March 1 of that year he came across Sandusky having anal intercourse in the football showers with a young boy whose hands were pinned against the wall. The 6-foot-4 former Penn State quarterback -- a onetime teammate of Sandusky's son Jon -- made eye contact with Sandusky, then 58, and the victim, whom McQueary estimated to be 10. But he did not intervene. Instead, after phoning his father (a health-care administrator affiliated with a local clinic to which Paterno has donated at least $1 million), McQueary conferred with Paterno the next day and told him what he saw. The coach then waited another day to speak to Curley. The athletic director then talked to Schultz, who relayed the incident to president Spanier. Except that as the account moved along the chain of command, the allegation apparently shed severity with each retelling. By the time it reached Spanier, it was merely behavior that, as Spanier testified, "made a member of Curley's staff 'uncomfortable.'" Unaccountably, though Curley saw fit to inform The Second Mile's director of the episode, neither he nor anyone else reported it to university police or any other police agency. Nor was there any attempt to identify or contact the boy.

Sandusky kept his office at Penn State and continued to have full access to the football facilities. The lone result of the 2002 incident -- a decision approved by Spanier -- is that Sandusky was prohibited from bringing children on campus. Don't do it here. Among all the graphic and horrifying detail in the grand jury testimony, this point is perhaps most damning.

Sandusky's alleged activity continued. It just moved elsewhere. The only two victims in the grand jury report whose identities remain unknown -- whom authorities couldn't contact -- were the ones assaulted on the Penn State campus. Had Sandusky not been so brazen in Mill Hall, had he simply restricted himself to the football facilities in State College, there is little to suggest he would have been caught. For Sandusky -- if not for the boys -- Penn State football was a safe haven.

While it may be imperfect, comparisons to the Catholic Church sex scandal are inevitable: A serial offender in a position of trust and power, with special access to youth, abused that position to commit heinous crimes. In the case of the church, says Jeff Anderson, a lawyer who has successfully represented sexual abuse victims against clergy, the predator benefited from a culture of insularity. "From low-level administrators to the top level, they looked the other way, and when they did see something, they chose to remain silent," Anderson says. Referring to both Penn State and the church, he adds, "When [the allegations] are revealed and reported and made known multiple times, there's a deliberate decision to protect the institution and reputation at the peril of the children."

Adds David Clohessy, director of Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, "Usually child molesters are charismatic, lovable folks on the outside. And many victims feel, I won't be believed; he'll be believed."

Unlike other sports scandals, this one will not fade once the season or the school year ends. There are pending criminal trials. Inevitably, there will be a raft of civil litigation. There will be multiple investigations, one of them headed by Penn State trustee and Merck president and CEO Kenneth C. Frazier, who has already vowed, "The chips will fall where they may."

Among the questions that demand answers:

• Particularly given his penchant for micromanagement and his power within the community, did Paterno know in 1998 that his top lieutenant was being investigated for sex crimes by the campus police and that a report was sitting on the desk of the local D.A.?

• Though only in his mid-50s and the most prominent assistant coach in college football, Sandusky retired after the 1999 season. Was there a connection with the '98 incident?

• Why didn't anyone, from McQueary to Paterno to president Spanier, at least inquire whether police -- or, for that matter, anyone -- had followed up on the 2002 incident?

• Why did it take a week and a half for Curley and Schultz to speak with McQueary after Paterno had passed them the information?

• The grand jury report and the attorney general assert that State College lawyer Wendell Courtney was counsel for both Penn State and The Second Mile in 1998, at which time he was told by Schultz about the '98 allegation involving Sandusky. Courtney did not return SI's phone calls but publicly denied he was the counsel to The Second Mile at that time. Which account is true?

• Why, after barring Sandusky from taking children onto the campus (a prohibition that Curley himself testified was unenforceable), did Penn State allow him to hold his summer camps on branch campuses?

• Having heard the allegations against Sandusky -- and, in McQueary's case, witnessing him allegedly raping a child -- how could Penn State officials abide his continued presence on campus?

More generally, what went through the minds of Paterno, McQueary and Curley when Sandusky would turn up at practice or lift weights in the workout room of the Lasch Building, as he reportedly did as recently as Oct. 31?

As to the familiar line of inquiry, "Who knew what and when did they know it?" accounts vary wildly. While former players and Sandusky acquaintances profess disbelief over the allegations, others in State College say the rumors had been marinating for years. "When [Sandusky] left, there was speculation about his behavior with young boys," says Rebecca Durst, who owns a barbershop near campus and says her long-term clients include prominent Penn State administrators. "This is a small town. It's been in the rumor mill for a while."

After the 2008 report from Mill Hall, The Second Mile quietly barred Sandusky from activities involving children. In September 2010, with the grand jury investigation well under way, Sandusky resigned from the charity he founded "to devote more time to my family and personal matters."

Outsiders now look back, parsing statements and rereading passages. Sandusky often asserted that one of The Second Mile's fundamental tenets was, "It's easier to develop a child than rehabilitate an adult." His autobiography, titled Touched: The Jerry Sandusky Story, recounts wrestling matches with kids and includes a photograph of Sandusky after a "pudding wrestling" bout. In the same book he offers Jer's Law: I allowed myself to be mischievous, but I didn't let it get to the point that someone would be intentionally hurt ... and I swore I would tell the truth if I was ever caught doing something wrong.

*****

In Mill Hall, Turchetta, already a stalwart of the community, is being cast as one of the few good guys in a sordid story. Folks in town were never shy about voicing their displeasure when Coach Chet didn't play their kid or ran on a passing down, but uniformly they appreciate what they perceive to be his courage. "I applaud what he did," says Miller, the wrestling coach who also testified. "This could still be going on if not for [him]."

In truth, that may be overstating the matter. Inasmuch as Turchetta is being lauded simply for doing what he was legally and morally obligated to do, it's because his behavior contrasted so sharply with the response at Penn State. The men in Mill Hall, outside the reach of the university and unencumbered by pressures of a big-time football program, did the expected thing.

Turchetta is resisting the hero role. He's referring the hundreds of calls he's receiving to the attorney general's office. Last Thursday afternoon he walked out of his district administration building wearing a solemn expression, his square jaw set off by a thick black mustache. "I'm just moving on," he said somberly. He paused, looked down and seemed to consider the surreality of his newfound fame. "Just moving on."

Healing will be far less swift an hour down the Nittany Valley in State College. While the crisis was unprecedented in its severity, the Penn State management was -- again, evidence of the school's insularity -- staggeringly clumsy. Press conferences were scheduled and then abruptly canceled. Remarks were tone-deaf. Spanier all but ordered his own firing when he declared his "unconditional" support for Curley and Schultz. When various administrators expressed shock at last week's revelations, even though Sandusky had been suspected multiple times and ThePatriot-News had reported in March on the grand jury investigation, it came across as more than a little disingenuous. Last week Penn State lecturer Steve Manuel veered from the syllabus for his communications class and spent the next several sessions dissecting the university's public relations disaster.

Clearly fed up with the school's spin, Paterno hired his own Washington, D.C.-based publicist and went off-message last Wednesday, candidly admitting moral culpability. He also announced that he would step down after the season. But his time for decrees was over. Hours later the board of trustees -- five of whom are former Penn State football players -- notified him by phone that, after 61 years, he was no longer an employee of the university.

Thousands of students left their dorms and apartments and swarmed Beaver Canyon, expressing their unhappiness with the decision. "You're digging JoePa's grave!" one female PSU swimmer despaired. As some students took part in a low-grade riot -- a few of them overturned or smashed cars, while the vast majority memorialized the night with their cellphone cameras -- a half-dozen football players stood at a remove, watching the scene and discussing whether any teammates needed to be extracted from the ruckus. One player, senior cornerback Chaz Powell, appeared ready to join the throng, vuvuzela in hand, but thought better of it. He tossed the horn in the trash and walked away.

On the other end of campus, a hundred or so students gathered outside Paterno's house, standing near an autumn cornucopia and a leftover Halloween ghost. Even after JoePa offered a short valediction, they stayed, most of them with moist eyes. At roughly 11:45, Sue Paterno opened the blinds, offered a wave of thanks, then turned out the lights.

*****

On Saturday, for the first time since the Truman Administration, Penn State took the field without JoePa in a coaching role. McQueary was absent as well, placed on leave. Tom Bradley -- another longtime Paterno assistant, who took over for Sandusky as defensive coordinator in 2000 -- served as interim head coach. (Sources tell SI some members of the board of trustees have insisted that Paterno's permanent successor must come from outside the Penn State family.) Dozens of former players stood on the sideline and sat in the stands, there to pay respects to JoePa and try to begin restitching at least a few strands of a badly frayed tapestry.

For all the ambient chaos over the last week, the tableau at Beaver Stadium was strikingly normal. Predictions of protests and mass tributes went unrealized, as though Nittany Nation was emotionally depleted, too spent to do much besides enjoy the diversion of football. Fields were full of tailgaters; the student section was loud but well-behaved; 107,903 people had filled the stands. The few earmarks of the Week That Had Been included a pregame "moment of silence for the alleged victims" -- at once poignant and sadly ironic, given the role silence played in aiding the unfathomable -- as well as donation boxes for child abuse prevention charities and a "blue out" in awareness of child abuse.

Understandably "out of whack," as Bradley put it, the team sputtered on offense and fell to Nebraska 17-14. Like the fans, the players projected exhaustion. "The hardest thing was how fast everything hit us; you can't even explain how everything changes," said senior defensive end Jack Crawford, who wore an eye-black patch under his eyes bearing the letters JVP. "It's sad to see how everything unfolded like it did, sad to see how it unraveled."

The crowd filed out quietly. A few headed to Paterno's house, tracing the route through campus that the most iconic coach in college football history had walked for all those decades. Outside the Creamery a line formed for scoops of Peachy Paterno, suddenly a nostalgic relic of a bygone era. A knot of students and alumni broke into an impromptu postgame cheer: "We are ... Penn State!"

So they are. Even if that no longer means what it once did.