The topsy-turvy year in sports

Seasons tell the whole truth, but they are hyphenated hybrids. Nobody rounds up "2010-2011." A single calendar year, however, turns sports on its head. In the self-contained universe of 2011, Cam Newton is a riches-to-rags tale: He wins the championship at the start, misses the playoffs at the end, and is basking on a beach somewhere in the blooper reel, long after the audience has left.

But that's OK. With the end of a calendar year comes a duty to take stock, to count inventory. The year must be measured and weighed. As with any sports transaction, we can't trade 2011 for 2012 until the former submits to a physical. Hold its X-rays up to the light and you can't tell if 2011 is right-side up or upside down, and that was true from Day 1, the year's birthday, 1/1/11.

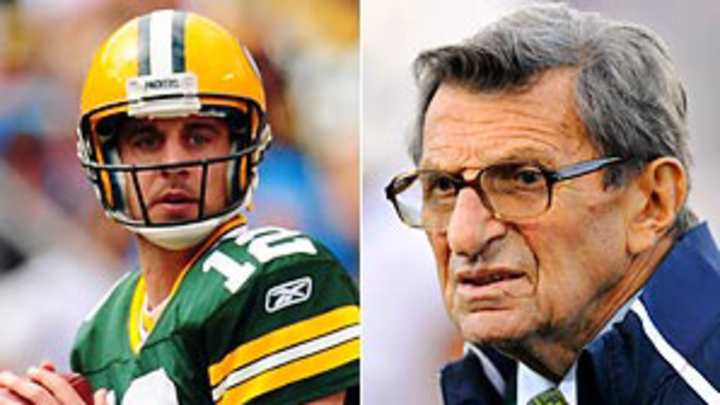

That was the day Florida beat Penn State in the Outback Bowl, in what was to be the final game for the winning coach (Urban Meyer, resigning to spend more time with his family) and not the final game for the losing coach. "The situation around me is very stable," said Joe Paterno, who had just turned 84. "The athletic director was a kid that I recruited as a walk-on. ... The president has been with us now maybe 14, 15 years. We have a lot of fun together. I don't see any reason to get out."

That the only man in the previous paragraph still working is Urban Meyer -- coach of Ohio State -- is testament to 2011 as a year of inversions. Innocent phrases -- Happy Valley, horseplay -- were imbued with malevolence. Billionaires engaged millionaires in "labor" disputes. Referees overturned touchdowns, Vancouverites overturned cars, college conferences were turned over like the drawers in a burgled house.

Fortunately, all of baseball was turned upside down, too, on the final night of the season, one of many happy upendings. Wayne Rooney's bicycle-kick game-winner for Manchester United against Manchester City showed there was much to fall heels-over-head in love with in 2011.

Rory McIlroy, 22, won golf's U.S. Open by eight strokes, fell head-over-heels for the top-ranked women's tennis player, Caroline Wozniacki, and gave her a lob wedge whose head -- but not, alas, whose heel -- was engraved with the couple's self-styled nickname: Wozzilroy. Wozzilroy has a distinctly Dickensian ring to it, and calls to mind Fezziwig, the happy anti-Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, which is appropriate, for there were few happier stories in 2011.

And yet one of those happier stories was, improbably, another Irish-golf-and-love story. For Darren Clarke, a Guinness in the clubhouse at Royal Sandwich -- after his emotional victory in the British Open -- was a fitting toast to his late wife, Heather.

But beauty is in the eye of the beer-holder, and in 2011, beer in the clubhouse was not everybody's cup of tea. For Red Sox pitchers, beer in the clubhouse caused a Great Unraveling in September, while at the same time introducing a memorable phrase into the lexicon. "Rally beers" will stand alongside "Wozzilroy" and "Tebowing" as top coinages of 2011.

Tebow the verb, of course, had nothing on Tebow the proper noun, as the Denver Broncos' quarterback, and his fourth-quarter heroics in Tebow Time, became Twitter's eternal Trending Topics, the barometer of national buzzwords with which Tim Tebow aptly shares initials.

While Tebow inspired fierce devotion or profound irritation, Albert Pujols -- in consecutive months -- inspired first one and then the other. After winning the World Series, Cardinals manager Tony LaRussa retired on top of the world, if not quite his profession, ending his career third on the all-time wins list, behind only Connie Mack and John McGraw.

As the one major sport whose season embraces the calendar year, baseball provided a Disney-fied ending to its own movie. But then Pujols did what Walt Disney did before him, and left Missouri for the riches of Anaheim. And Ryan Braun, the National League MVP, tested positive for PEDs days before Barry Bonds was sentenced to house arrest.

It was impossible to think of houses and arrests and baseball in 2011 without recalling the man who entered and occupied the Chicago residence of Ken Williams while the White Sox GM was away. The intruder, as the police report took special glee in noting, defrosted a lobster. Police entered with drawn guns. Or at least drawn butter.

Alas, selfish acts got more attention than shellfish acts in 2011. First the NFL briefly locked out its players. When it was the NBA's turn, there was much angry fist pounding before anything was resolved. There always is when an owner tries to lock out a subject. Think of Fred Flinstone and his cat.

For a year in which every other athlete or story sounded like a new model of Mercedes -- "CP3," "RGIII," "DJ3K" -- the flashiest car was the Kia over which Blake Griffin jumped in the NBA dunk contest. He collected a ball en route from Baron Davis, who popped out of the sunroof like a jack-in-the-box -- a jack-in-the-box at a Jack-in-the-Box drive-through.

In the NBA Finals the Dallas Mavericks' victory over the Miami Heat was widely celebrated as the rich getting vanquished by the slightly less rich -- Southfork 1, South Beach 0 -- further evidence that LeBron James has become bigger in villainy than he ever was as a hero.

Thus the NBA's presumptive best team, the Heat, failed to join the celestial company of a very few athletes operating at the peak of athletic powers in 2011. Rodgers and FC Barcelona were near-perfect exemplars of football and fútbol. In winning three tennis Slams, Novak Djokovic looked -- with Roger in retrograde -- set to dominate for years. Tigers pitcher Justin Verlander was an unstoppable force, Bruins goalie Tim Thomas an immovable object.

And all the while the real world turned, rife with revolution. As statues toppled, and dictators were deposed, sports and sports alone -- thanks to the Laker formerly known as Ron Artest -- brought World Peace.

It was that kind of year. Here's to the next one. Mazel tov, Wozzilroy.

Special Contributor, Sports Illustrated Steve Rushin was born in Elmhurst, Ill. on September 22, 1966 and raised in Bloomington, Minn. After graduating from Bloomington Kennedy High School in 1984 and Marquette University in 1988, Rushin joined the staff of Sports Illustrated. He is a Special Contributor to the magazine, for which he writes columns and features. In 25 years at SI, he has filed stories from Greenland, India, Indonesia, Antarctica, the Arctic Circle and other farflung locales, as well as the usual locales to which sportswriters are routinely posted. His first novel, The Pint Man, was published by Doubleday in 2010. The Los Angeles Times called the book "Engaging, clever and often wipe-your-eyes funny." His next book, a work of nonfiction, The 34-Ton Bat, will be published by Little, Brown in 2013. Rushin gave the commencement address at Marquette in 2007 and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters for "his unique gift of documenting the human condition through his writing." In 2006 he was named the National Sportswriter of the Year by the National Sportswriters and Sportscasters Association. A collection of his sports and travel writing—The Caddie Was a Reindeer—was published by Grove Atlantic in 2005 and was a semifinalist for the Thurber Prize for American Humor. The Denver Post suggested, "If you don't end up dropping The Caddie Was a Reindeerduring fits of uncontrollable merriment, it is likely you need immediate medical attention." A four-time finalist for the National Magazine Award, Rushin has had his work anthologized in The Best American Sports Writing, The Best American Travel Writing and The Best American Magazine Writing collections. His essays have appeared in Time magazine andThe New York Times. He also writes a weekly column for SI.com. His first book, Road Swing, published in 1998, was named one of the "Best Books of the Year" by Publishers Weekly and one of the "Top 100 Sports Books of All Time" by SI. He and his wife, Rebecca Lobo, have four children and live in Connecticut.