Examining Donald Sterling's lawsuit and how it impacts the NBA

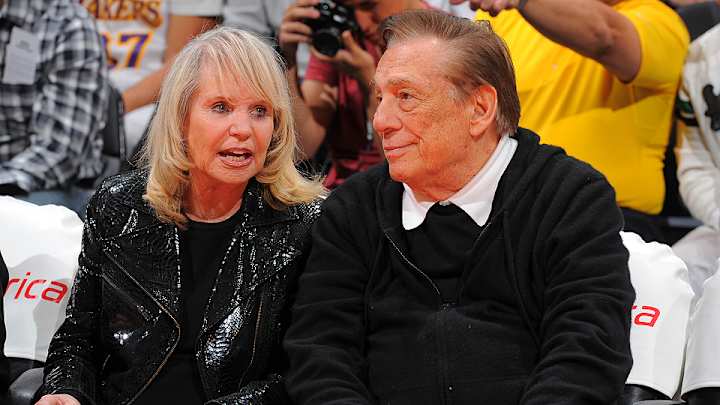

Donald Sterling is regarded as the NBA’s most litigious owner for a reason. The 80-year-old billionaire is waging a multi-front legal campaign to preserve his financial stake in the Los Angeles Clippers. Sterling is expected to appear in Los Angeles County Superior Court on Monday to litigate against his wife of 59 years, Shelly Sterling. The most pressing issue in this state court hearing is whether she lawfully reached an agreement to sell the Clippers to former Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer for $2 billion. The hearing, however, might be postponed or even canceled, as Donald Sterling has petitioned a federal court to hear the dispute.

The NBA is not a party to the Sterlings’ family squabble, but has a vested stake in its timing and resolution. In April, NBA commissioner Adam Silver permanently banned and fined Sterling for violating the league’s constitution. Sterling’s alleged violation stemmed from his racially insensitive remarks to V. Stiviano and the resulting financial and reputational harm suffered by the NBA. Since then, Sterling has given a much-criticized interview with CNN’s Anderson Cooper, sued the NBA for $1 billion and described league officials as “despicable monsters.” At the same time, the league has installed former Time Warner CEO Dick Parsons to run the Clippers and moved to completely sever ties with Sterling. The league’s legal strategy against Sterling would be delayed and possibly made more difficult if Shelly Sterling lacked the legal capacity to negotiate with Ballmer.

Overview of the Sterlings’ probate dispute: a matter of trust

Barring intervention by a federal court, Judge Michael Levanas will preside over the Sterling hearing scheduled to begin on Monday. Levanas, who was appointed by then-Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2005, has indicated the hearing should last four days. The hearing will center on the Sterling family trust, which owns the Clippers and which identifies Donald Sterling and Shelly Sterling as trustees. Levanas will decide if Donald Sterling ceased serving as a trustee, thereby leaving Shelly Sterling as the sole trustee.

According to Shelly Sterling, neurologist MerilPlatzer and psychiatrist James Edward Spar separately evaluated Donald Sterling’s cognitive state on May 19 and May 22. They utilized a CT scan and a PET scan of Donald Sterling’s brain taken days earlier at Cedars Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. After review, Platzer and Spar concluded that Donald Sterling was incapacitated, meaning unable to discharge his duties and obligations under the trust. Spar, for instance, warned “Mr. Sterling is at risk of making potentially serious errors of judgment, impulse control, and recall in the management of his finances and his trust.” In fairness to Sterling, he has reportedly received a favorable assessment of his mental capacities by prominent neurologist Jeffrey Cummings of the Cleveland Clinic.

Still, the declaration of Donald Sterling as incapacitated was an important legal development for the future of the Clippers. The Sterling trust stipulates that if either Sterling is incapacitated, the other takes full control of the trust. Shelly Sterling, acting on what she believed was full control, reached an agreement on May 30 to sell the Clippers to Ballmer. Six days later, Donald Sterling stunned the world by signaling support for the sale. Sterling’s support, however, was apparently premised on a mistaken belief that the NBA would rescind his ban and fine as a gesture of good will. The NBA made no such gestures.

Reversing course on his approval of the sale, Donald Sterling signed a statement on June 9 expressing that the family trust was revoked. He undertook this action with the hope of blocking the sale of the team. If Sterling possessed the legal capacity to revoke the trust, the trust would no longer own the Clippers and ownership would revert to both Sterlings. Even in that scenario, the $2 billion deal reached by Shelly Sterling with Ballmer would not necessarily be off. Keep in mind, the Ballmer deal was struck on May 30, 10 days before Donald Sterling moved to revoke the trust.

Although Ballmer cannot become the team’s owner until a sale is approved by the NBA’s Board of Governors, the contract he reached with Shelly Sterling still creates legal obligations for both. Moreover, revocation of a family trust normally isn’t instantaneous. Instead, it usually involves a “winding down” period of weeks or months. Shelly Sterling would contend that she should control the family trust during any winding down period. Such a period might give her enough time to finalize the sale to Ballmer.

What to expect in the probate hearing: the judge’s review of the Sterling trust’s procedures

During the hearing, Levanas will closely scrutinize the language of the Sterling trust and its procedures. He will assess whether the trust has been correctly interpreted and applied in good faith by both Sterlings. If Levanas identifies no procedural errors in the evaluations of Platzer and Spar, and finds no misconduct by Shelly Sterling, he would be inclined to hold for Mrs. Sterling. If Levanas does so, he would pave the way for the NBA to approve the sale of the team to Ballmer.

Donald Sterling contends that he was duped into undergoing neurological examinations, and that these examinations were incomplete and conducted unprofessionally. For instance, Sterling claims that after Platzer evaluated him at the Sterling residence on May 19, Platzer and both Sterlings consumed alcoholic drinks at the nearby Beverly Hills Hotel. The inference is that the so-called examination by Platzer was more of an informal social encounter than a medical evaluation. In addition, expect Donald Sterling’s lawyers to portray Shelly Sterling as clouded by greed and as failing to satisfy a fiduciary duty of good faith to the trust. Similarly, they might assert that she had a financial conflict of interest in retaining Platzer and Spar to “independently” evaluate her husband.

Levanas will also scrutinize Donald Sterling’s conduct with respect to the trust. He’ll weigh that Sterling, an attorney by trade, was reportedly represented by attorneys during the time when he agreed to be neurologically evaluated. Along those lines, perhaps Sterling should have known better than to agree to meet with neurologists retained by his wife. This critique seems especially persuasive given that Sterling -- and the rest of the American public -- was probably on notice of Shelly Sterling’s possible intentions. To wit, Shelly Sterling told ABC’s Barbara Walters on May 11 she thought her husband was suffering from dementia.

The judge’s review of the “best interests” of the trust

In addition to assessing whether the trust was interpreted correctly and ethically, watch for Levanas to consider the best interests of the trust. Under Shelly Sterling’s leadership, the value of the trust appears to be $2 billion, as that is the price offered by Ballmer to buy the team. For at least two reasons, the trust may lose significant value if Donald Sterling regains control.

First, the record-setting deal with Ballmer would be jeopardized and, although unlikely, Ballmer could file a lawsuit against the trust. After all, Ballmer signed an agreement with the trust under the assumption that Shelly Sterling possessed the legal authority to unilaterally act on its behalf. If Shelly Sterling had no such authority, then she wrongfully entered into contracts on behalf of the trust. To be sure, Ballmer likely knew, or should have known, that Donald Sterling would present a legal challenge at some point. Ballmer and Shelly Sterling, moreover, contractually agreed to resolve most of their potential disputes in arbitration, and thus outside of court. Still, Ballmer might sue for breach of contract and contend that he has been legally damaged by having a team taken from him.

As a second consequence of Donald Sterling regaining controlling of the trust, NBA players could reinstitute threats to boycott games, star players might become less interested in playing for the Clippers and sponsors might again drop their Clippers’ contracts. Consequently, the Clippers’ fan base could be adversely impacted and become less willing to spend money on the team. To the extent Levanas considers the best interests of the trust in his decision-making, these factors appear to be an advantage to Shelly Sterling.

Donald Sterling’s petition to federal court

The hearing before Levanas, a state court judge, might never happen. Last Thursday, Donald Sterling filed a notice of removal to federal court. Sterling contends that the disclosure of his medical information violates the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (“HIPAA”). According to Sterling, this allegation raises a question of federal law for review by a federal judge.

For at least three reasons, Sterling’s attempt to involve a federal court will probably fail. First, paragraph 7.5.c of the Sterling trust expresses that Donald Sterling and Shelly Sterling waived their HIPAA privacy rights for purposes of determining whether either is incapacitated. This waiver suggests Donald Sterling contractually relinquished the right to pursue HIPAA claims.

Second, HIPAA itself does not contain a “private right of action,” which refers to a private citizen’s legal capacity to file a lawsuit under the law. Although on occasion courts have permitted private citizen claims under HIPAA, the odds are clearly stacked against Donald Sterling.

Third, states judges in California have heard HIPAA claims. This suggests that Levanas could hear a viable HIPAA claim brought by Donald Sterling and thus removal to federal court would be unnecessary.

The significant power of delay in a world of tight schedules

Despite the dim outlook for Sterling to be heard by a federal judge, his attempt could delay the state court proceedings. Levanas may be inclined to wait for resolution from a federal judge and that could take days or longer. This presents a scheduling problem for Levanas: he has a trial calendar and the Sterling matter is one of many proceedings before him. To re-schedule the Sterling matter could mean that it is not heard for weeks.

Therein lies a scheduling problem for Shelly Sterling, Ballmer and the NBA. Ballmer’s agreement with Shelly Sterling is set to expire on July 15, which not coincidentally is the same day the NBA’s Board of Governors is scheduled to vote on Clippers sale. If a vote takes place, approval would be a mere formality. Ballmer is widely respected by the NBA and he already received favorable evaluation when attempting to purchase the Sacramento Kings last year. Robert Raiola, a senior manager in the Sports & Entertainment Group of the accounting firm O’Connor Davies, LLP, estimates that approximately $662 million of the $2 billion received by the Sterlings in an approved sale would be paid in state and federal capital gains taxes.

The agreement Ballmer reached with Shelly Sterling could be extended by 30 days, but the NBA has a finite amount of patience. The league wants new Clippers ownership by the start of the 2014-15 season and has indicated the Sterlings must sell the team by September 15.

NBA’s Plan B: terminate Donald Sterling’s ownership

The NBA would obviously prefer that Shelly Sterling win the probate hearing, as the league’s path to ownership transfer would be made nearly certain. If instead Donald Sterling wins, or is able to significantly delay probate proceedings, the NBA would resort to its original plan: terminate Donald Sterling’s ownership. Sources familiar with the NBA’s legal strategy have told SI.com that if Donald Sterling retakes control if the Clippers, the league will hold the termination hearing that it originally scheduled for June 2.

As explained in a previous SI.com column, the termination hearing would be similar to an arbitration hearing, with representatives of the commissioner’s office and Sterling’s attorneys debating the merits of his expulsion from the league. Unlike a trial, there would flexible rules of introducing evidence and witness statements. Minnesota Timberwolves owner Glen Taylor, chairman of the Board of Governors, would be the presiding officer and act as the de facto judge or arbitrator, and the 29 controlling owners would act as jurors. Per Article 14(g) of the NBA's constitution, if at least 22 of the 29 owners sustain the charges against Donald Sterling for violating Article 13 of the constitution, the Clippers’ membership in the NBA would be “terminated.”

This would have the practical effect of ending both Sterlings’ ownership of the Clippers and the NBA would put the team up for sale. Ballmer would presumably bid again for the team but he would not be assured of getting it. The Sterlings would subsequently receive proceeds from the team’s sale, minus expenses incurred by the NBA.

While the NBA is confident at least 22 of the 29 owners would vote to sustain the charges against Sterling, it is possible that several owners would have reservations. This seems especially possible given that the height of the Sterling controversy has passed. Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban, for instance, has publicly wondered about a “slippery slope” caused by terminating the ownership of a fellow owner for remarks made in private. Another potential concern among owners is that if the NBA terminates Donald Sterling’s ownership, he would be more likely to continue his lawsuit against the league. If Sterling’s lawsuit advances past an NBA’s motion to dismiss, he might use pretrial discovery to embarrass owners about their own personal failings.

The NBA does not appear overly concerned about these worries, but all things being equal, the league would prefer to avoid a termination hearing. This is among the reasons why the probate hearing in Los Angeles is so crucial for the future of the Clippers.

Michael McCann is a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. He is also the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law.