No Exit: Carmelo Anthony, the New York Knicks and the unhappy sports marriage

There is one hard and fast rule to keep in mind about the relationship between management and labor in professional sports. It has been the rule ever since the reserve clause fell in baseball, and since free agency came in there and everywhere else. The previous rule was pretty much that you took what management offered or you took the job with your father-in-law’s beer distributorship in Barstow. Everybody—players, owners, most sportswriters, and almost every fan—took this as iron law. Then the rule changed utterly into the one that exists now, and the one that should be consulted during any discussion of free agency, trades, or other forms of personnel moves.

Nobody makes anyone do anything.

(I guess I could say The Invisible Hand of the marketplace makes them do it, but then I might wake up tomorrow morning and discover I was working on the Council of Economic Advisors and, I assure you, nobody wants that.)

Nobody forced the Texas Rangers to give Alex Rodriguez a 10-year, $252 million contract in December 2000. Nobody forced the Yankees to pick up that ridiculous contract three years later, and nobody forced the Yankees to give him another 10 years and another $275 million after the 2007 season. When the contract began to look ridiculous, and the relationship went to knife’s point, it was nobody’s fault because it was everybody’s fault. As C.J. Cregg once said on The West Wing about political difficulties, “There are no victims, just volunteers.”

Which is why when everything goes sour and the relationship between a player and a team deteriorates to the point of anonymous slanging in the newspapers and semi-literate slander on the talk shows, all of it is a little pointless. Nevertheless, it’s an interesting phenomenon to observe what happens when all of the escape mechanisms break down and a player who doesn’t want to be there and a team that doesn’t want him there end up stuck with each other.

Why Sidney Moncrief Deserves To Be In The Hall of Fame

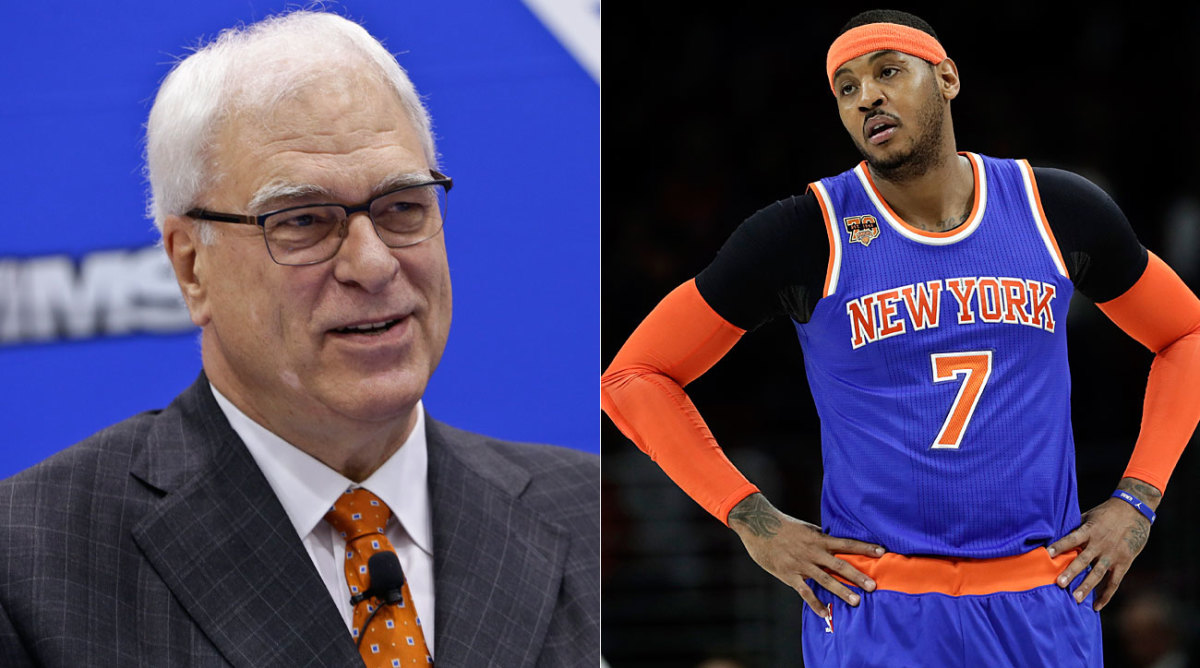

The most prominent example these days, of course, is the very strange situation involving 10-time All-Star forward Carmelo Anthony and the New York Knicks. (Or, perhaps I should say, one of the very strange situations involving the New York Knicks, because when one of your former stars gets into a beef with your unpopular owner in the middle of a game, your entire franchise pretty much has taken up playing its home games in the Twilight Zone.) Given their druthers, the Knicks, headed toward a fourth straight finish outside the postseason, would rather be rid of Anthony, having reportedly tried to trade him already this season. Given his druthers, Melo likely would prefer to leave New York's bleak present behind. Unfortunately, and not because anyone made them do it, the team and the player had previously agreed to a contract that contains a no-trade clause, and that will pay Anthony, 32, north of $26 million next year, with a player-option worth almost $28 million for 2018-19.

The NBA trade deadline came and, elsewhere in the league, general-managers took a look at the deal and either collapsed in laughter or hurled themselves out the window before the temptation to ad a player averaging more than 23 points per game got too great. And so here the Knicks and their reluctant star remain, locked in a relationship side appears to be enjoying very much.

There are precedents, of course. The Yankees and A-Rod had to endure each other for years before A-Rod was finally released last August. In 2003, the Red Sox offered up Manny Ramirez on irrevocable waivers, free for any team in baseball to pick up. Everybody passed. Of course, the next season, the Red Sox won their first World Series in 86 years, and one in which Ramirez was the Most Valuable Player. Something similar, but with far less public bad blood, occurred this year when Pittsburgh offered Andrew McCutchen around during the winter meetings only to have nobody take them up on it, so McCutchen is, at the moment, the Pittsburgh rightfielder. In the NFL, the Redskins bumped one-time franchise quarterback Robert Griffin III all the way to scout-team defensive back in 2015 before they could cut him loose.

With free agency—and, to be clear, the coming of an actual marketplace of talent—came all the risks inherent in any marketplace. Ever since that happened, however, the management side of affairs has worked assiduously to minimize its downside by tampering with the market mechanisms. The most obvious strategy was the collusion engaged in by the baseball owners in the late 1980’s. On the labor side, a lot of the risk is eliminated by the existence—everywhere except in the NFL—by the invention of the guaranteed contract. (Although, in any other context except professional sports, a “guaranteed contract” sounds very much like a redundancy.) Nevertheless, at the same time, the new millions guaranteed by those contracts became another way for the public to measure performance and, more specifically, failure. It commodified human beings in a new way through the familiar metric of cold, hard cash.

NBA Mock Draft 2.0: Mock Before The Madness

The ability of players to determine their own fate and the grudging acceptance of management of that reality has unquestionably been a boon to every league in every sport. But the new dynamic laid its own traps. For almost 50 years, each side has fought to create a system that suited its own needs. Players could move more freely, which caused teams to pay more freely, and that was a good thing no matter what how management propaganda tried to spin it. But there also arose a kind of dead-end business dynamic for which there was no solution. The current dilemma with the Knicks and Carmelo Anthony is a result of the fact that the institutions of professional sports are still groping with their own economics.

So, eventually, these kinds of situations became inevitable. Back in the day, if a baseball team found a player more trouble than he was worth, they could simply peddle him and make him somebody else’s problem. Once free agency hit, a player who felt ill-used needed only to be patient until he was able to move along to where he was more appreciated, financially and otherwise. However, in the constant push-and-pull of labor negotiations over the decades, with compromises and carve-outs and attempts by both sides to improve their advantage on behalf of their primary constituencies, an infrastructure has been created that contains both escape hatches and blind alleys. In situations like the one facing the Knicks and Carmelo Anthony, it’s as though both team and player are stuck in a maze with no real way out.

This leaves everybody twinsting in the winds that blow through the legendary Court Of Public Opinion which, in my experience, has no windows and no walls and is stirred by great gusts of hot air. It’s what we have these days instead of Roman triumphs, but it’s also what we have these days instead of a pillory. Instead of being hung up in the town square so that the peasants can throw tomatoes at you, you get hung up on the radio or on the Internet, so that Bob On A Cell Phone or @sportsgoober1 can get their licks in. The Knicks get pelted because of the mismanagement that has plagued the team for season after season. Anthony gets pelted because, rather than Phil Jackson or James Dolan, Charles Oakley’s good friend, Anthony is the living, walking, jump-shooting symbol of that mismanagement. But nobody forced anybody to do anything, and there are no victims here, just volunteers.