Ibtihaj Muhammad was a sophomore at Columbia High in Maplewood, N.J., about 20 miles from Manhattan, when the World Trade Center fell. The future Olympic bronze-medalist fencer was one of only several Muslims in her community—she remembers maybe one or two other families in the area—and the only person at her school wearing a hijab.

Maplewood was a commuter town; parents sent their children to class, then boarded the Morris and Essex line into the city for work. Muhammad was in her AP English class on the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, when her teacher, like others across the country, watched through fingers as news footage captured just miles away played out across a television. First, smoke from the north tower filled the screen. Then came the panic.

After United Airlines flight 175 struck the south tower, Muhammad’s principal took to the loudspeaker and instructed teachers to turn off their TVs. Parents of students at the school worked in those buildings. They didn’t need to experience their panic and grief so publicly.

But the principal did something else, too: “We were called to sit in this room,” remembers Muhammad, who’s now 35. “My brother, this Egyptian family … . It was like, You just stay here.”

They were being separated for their safety, the sequestered students were told, but Ibtihaj remembers sitting there with the few other Muslims students who were pulled from their classes. Even if their removal was well-intentioned, it ostracized them from peers. It was ghettoizing.

And Muhammad’s experience wasn’t unique. Muslims became a lower class of citizen in a country now fearful and filled with hatred toward them. I was one of them. I was 5—a Muslim first-grader living in rural Michigan, surrounded by folks whose image of Muslims or Arabs would come to be shaped by 24 and NCIS.

I don’t remember the towers falling. My understanding of what happened is pieced together through videos and retellings. But I do remember September 11. I remember coming home from school to find my mother, panicked and shaken, halfway up the stairs to my bedroom. “Did they tell you in school about what happened today?” she asked. They hadn’t.

She explained to me, with simplicity and caution: People had attacked the United States. People from a place near Syria, where my parents were born, long before they immigrated in 1990. Then, in a moment of clairvoyance, she sighed and looked me square in the eyes.

“Things are going to be different now.”

The last 20 years of U.S. policy, at home and abroad, have borne out that truth. The world changed on a macro level, and for me, on a personal one. Wars gave way to an onslaught of Islamophobia, attacking anyone who practiced the faith or even remotely resembled those who did. Targeted harassment policies were codified and the words “Middle Eastern” and “Arab” and “Muslim” became synonymous with “terrorist.”

Muhammad (far right) in Rio, where she earned a 2016 bronze medal in team sabre.

Bob Martin/Sports Illustrated

It didn’t matter that my parents were accomplished in their fields, the same way that it wouldn’t matter later that Ibtihaj Muhammad was an accomplished fencer, a medalist for the U.S. In the eyes of many, she remains a Muslim first and foremost. The lost story of September 11 is the story of September 12, the day Muslims in America woke up to a new reality. One that’s continued each morning since.

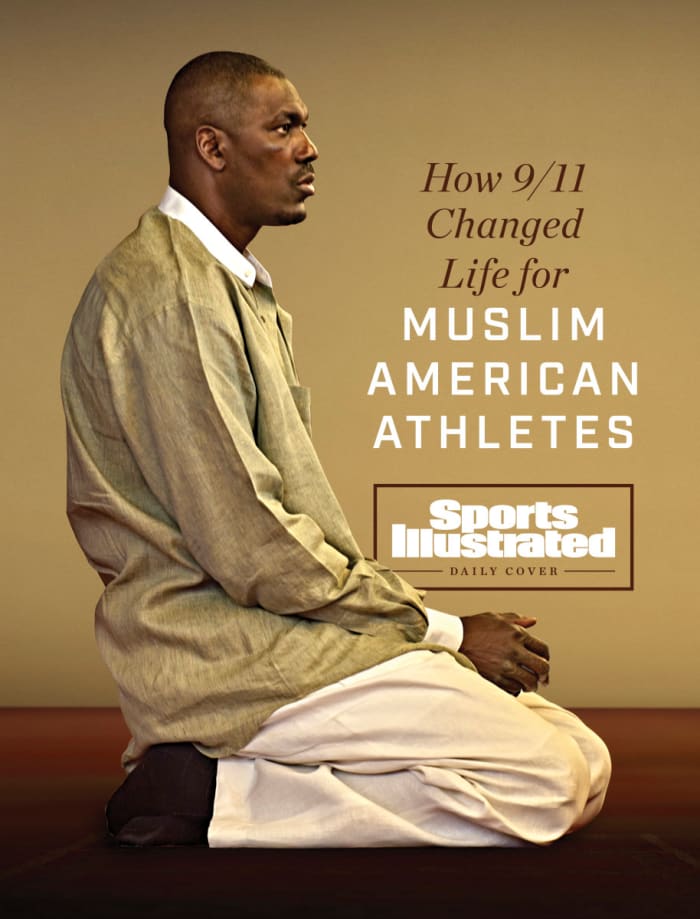

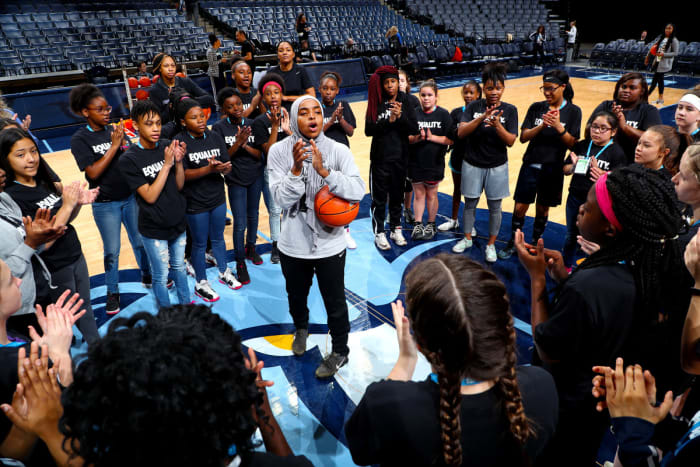

Bilqis Abdul-Qaadir remembers what it was like when she first started wearing a hijab. She was a ninth-grader at the New Leadership Charter School in Springfield, Mass., in the mid-2000s—her second year of public schooling after having been taught at home. In the eighth grade she’d made the high school basketball team, but it wasn’t until a year later, as a freshman, that she covered her head, as well as her arms and legs.

Playing in a hijab wasn’t easy. She didn’t know many other Muslims around town; she couldn’t turn to older girls for advice on how to make the garment suit an athletic activity. At the time, she wore a makeshift covering—a clunky affair made of sweatpants or T-shirts, wrapped like a turban. She couldn’t use pins or needles to secure it; that would have been unsafe on the court. And the world was years away from a Dri-Fit version.

Encumbered though she may have been, she went on to be named Massachusetts’s 2009 Gatorade Player of the Year, averaging more than 40 points a night. But to some opposing fans from Catholic schools in less-diverse neighboring towns, she was a target for harassment. “It made me conscious of my dress,” says Abdul-Qaadir, now 30. “I was called ‘Osama Bin Laden's niece.’ Everytime I step on the court I'm looking at the crowds, because I see people pointing and laughing, making jokes.”

In the beginning, the hecklers scared her and made her self-conscious. She noticed that the same people calling her names were often the same ones who approached her after games, impressed by her dominance, and asked about her hijab. What is it? And why do you wear it? They’d never met a Muslim, they’d tell her.

The unwanted spotlight followed Abdul-Qaadir to the University of Memphis, and then to Indiana State, where she transferred for her final year of eligibility. She remembers playing on the road with the Tigers against Tulsa, and how the men’s players in the crowd heckled her for wearing a hijab. She remembers how students at Bradley had to be removed from the stands after they hurled hate speech at her. She remembers the game that had to be stopped temporarily, so bad had the harassment gotten. But most of all she remembers how, in many people’s eyes, she was always the Muslim basketball player—a caricature, not a fully formed person.

With Memphis, in a game against Houston, an errant swipe from a ball-hungry opponent as she drove the lane unintentionally knocked the hijab off her head. Abdul-Qaadir dropped to the floor in a panic as her teammates huddled around her, shielding her from the crowd as she scrambled to reaffix her headwear. Years later, she remembers: At halftime, the game’s TV broadcast had run a segment about her hijab and why she wore it. There seemed a degree of understanding. And yet, when the hijab fell off, the TV cameras zoomed in, invasively, trying to get a better look.

At a Title IX summit in 2018, Abdul-Qaadir addressed young girls of all ages.

Joe Murphy/NBAE/Getty Images

Abdul-Qaadir saw for herself a basketball life after college; she planned to play professionally in Europe. But FIBA, the international body governing the game, barred athletes from wearing hijabs. At first, Abdul-Qaadir wasn’t concerned. They would see her play and realize that her hijab wasn’t a safety concern, she figured. It wouldn’t be a problem. But quickly she realized FIBA wouldn’t budge. She had to make a choice: her sport or her faith. She admits that it wasn’t always a clear one.

“I was getting ready to, honestly, take my hijab off,” Abdul-Qaadir remembers. “I was questioning the hijab. I was like, There's no way I worked this hard to reach my goal and to then have it taken away because of my hijab.”

It was a personal crisis. For so long she’d been the Muslim basketball player. When the game was taken away, she says, she was just the Muslim. She was embarrassed that she even considered removing her headscarf; she didn’t tell her family, just one close Muslim friend. Without the game, she lost the part of her life that helped her blend in and win affection from fans. If not for those fans, she might have given in.

“Young Muslim girls from across the world were learning about my story and emailing me, sending me pictures of them dressed just like me, in a basketball uniform,” Abdul-Qaadir says. “This wasn’t about me anymore.”

Hers was a choice between faith and the sport she’d devoted her life to. And that choice ended her career. Abdul-Qaadir never played a minute of professional basketball, but she still changed the sport for those who followed her, petitioning FIBA (along with Indira Kaljo, a Bosnian Muslim at Tulane whom Abdul-Qaadir had played against) to drop the restriction. The fight took three years, but in 2017 the association rescinded its ban, paving the way for Muslim women to compete on their own terms.

Even in a sport where wearing a hijab isn’t illegal, it can still complicate seemingly simple things. As Ibtihaj Muhammad climbed the ranks of fencing, all the way to the Rio Olympics, she switched from a child’s hijab (tied in the back and pinched in the front, secured with a safety pin) to a georgette fabric, doubled onto itself and then pinned into place under her fencing helmet. Functionally, it was passable—it covered her hair—but the four thin layers retained sweat, creating a new problem.

“When it got wet, I couldn't hear,” says Muhammad, who was at risk of losing crucial points. “My entire career, I had no idea. When the official would say, ‘Start,’ sometimes I couldn't hear.”

It wasn’t until 2017, after her fencing career ended, that Nike (with Muhammad’s help) developed the Pro Hijab: a moisture-wicking Dri-Fit headscarf that made obsolete the makeshift hijabs that she and Abdul-Qaadir had worn. A singular sport product, designed for Muslim women, goes beyond making it easier for them to compete at the highest levels. It spares young girls the complexities and fears attendant of the headwear.

“For a lot of us, for a really long time, not having … a sport hijab was an excuse not to be active,” Muhammad says. And that “goes against the tenets of our faith, to take care of yourself and your body. … It’s given us permission to be active.”

The wider acceptance of the hijab is part of what Muhammad says has been a concerted effort by Muslims to combat Islamophobia in the two decades following September 11. Younger Muslims aren’t bending to a world that has harassed and villainized them. They’re demanding the world bend toward them. It’s part of what Muhammad calls “a wave of strength.”

“As a Black Muslim, that desire to conform has never been a part of who I am,” she says. “We [don’t] need to look a certain way or pretend to be things we’re not.”

Hakeem Olajuwon wasn’t always a devout Muslim. Back in Lagos, where he was raised, Islam was Olajuwon’s culture more than it was his religion. He’d listen to an Imam call worshipers to prayer on the radio, fast on the holy month of Ramadan and attend the mosque on Fridays with his father. But within a few years of arriving Stateside, in 1980, he wasn’t actively participating anymore. Eventually, in Houston, he was so removed from his faith that when someone asked him whether he was headed to the mosque he was shocked to hear there was one nearby. He’d never looked. Olajuwon was skeptical at first—he didn’t know what to expect until a familiar sound swallowed the silence.

“It was the first time I heard the call to prayer in about two years,” Olajuwon says. “And I couldn't stop crying.”

Thereafter, if the Rockets, say, played in Phoenix, he’d ask the bellman at the team hotel to book him a ride to the closest mosque. Wherever Houston traveled, the same thing. At first, it was just a way for Olajuwon to connect with his God. Soon, it gave him a family.

In time, members of the communities he visited started to recognize him each time he came back through town. Local leaders introduced themselves. Others invited him over for dinner, or offered to drive him to and from the airport. Across the country, Muslims knew: If the Rockets are in town tomorrow, you can expect to see Hakeem at the Isha prayer tonight.

“When we travel, you don’t know anybody,” Olajuwon says. “Then all of a sudden … the community [knew me]. So, life on the road, for a Muslim—I've never felt like I'm on the road. I'm always at home.”

As Olajuwon became more comfortable expressing his faith, he practiced it more openly. Early in his career, he fasted during Ramadan, with the exception of game days. Muslims, according to Islam’s teachings, can skip fasting during the holy month if they have good reason, such as illness or old age or pregnancy. But the texts don’t cite “backing down David Robinson” as a reason to break fast, and so when Ramadan fell in February in 1995, Olajuwon concluded that he ought to fast, even on game days.

Olajuwon in 1994, shortly before he started fasting during games in Ramadan.

Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated

Some of his teammates and coaches expressed concern—Think of the energy expended by even the most static of NBA big men!—but Olajuwon quickly mollified their fears. Fueled by the spare dates and the few sips of water that he consumed at halftime, after the sun had set, Olajuwon would come out of the locker room roaring in the second half. In his first game fasting, he scored 41 points on Karl Malone; he outdueled Charles Barkley, Patrick Ewing and Robinson in the coming days.

Fasting, he says, made him sharper, lighter and more disciplined. Halftime dates were his own version of Michael’s Secret Stuff. The dried fruits—the same as the Prophet Muhammad ate to break fast centuries earlier—propelled him. He ended that February as the league’s Player of the Month. He’d fully reclaimed his faith. He was home.

Fast forward six years, to 2001, when he was traded to the Raptors, and Olajuwon was in unfamiliar territory, outside of Houston for the first time in more than 20 years. Then, a month after he arrived, the towers fell. Suddenly, Olajuwon was forced to play defense off the court.

“Islam had been looked at from a positive light all my career, until 9/11,” says Olajuwon, who’s now 58. “Then all this negativity started, which is totally the opposite of what Islam teaches.”

The burden fell on Olajuwon and his fellow Muslims, the former NBA MVP says, to explain to those who might wish them harm: Your vision of Islam is a distortion of reality. And while Olajuwon admits that Islam is too big for any one person to represent, he acknowledges the role he’s had to play in defending his faith. “You feel like you have to convince the people, That's not Islam,” Olajuwon says. “You have to justify your position as a Muslim, being, all of a sudden, the enemy.”

Pushing back is a role he’s embraced. “I’ll take the opportunity,” he says, “to shape the perception of what Islam really is.”

Still, those perceptions weigh heavily on many others. Husain and Hamza Abdullah—Los Angeles–born siblings and former NFL defensive backs—were raised in a small but devout Muslim community made up of immigrants from across the Middle East. For them, religion started at home and with sporadic trips to the mosque in the big city. They had fellow Muslims to lean on, and they had each other.

As they progressed through their college careers, both at Washington State and then as professionals in the NFL, they stayed devoted to their faith. Still, it tested them. Islam follows the lunar calendar, which is 11 days shorter than the Gregorian calendar used in the U.S.; thus, Ramadan comes earlier each year. Husain, the younger of the two brothers, was a senior in high school a year after the towers fell, when he first fasted during a football season. It was difficult, he remembers, running drills in practice, staying disciplined in games, all without a sip of water or a bite of food. And harder still, doing it in secret.

It wasn’t until Husain’s third year in the NFL, in 2010 with the Vikings, that he first let on to teammates and coaches that he was fasting. The brothers didn’t want special treatment. But, more than that, as players always living on a roster’s fringe, they were worried that fasting would be used as a reason to cut them. “Nobody’s gonna come out and say that, but behind closed doors, fasting may be a conversation,” says Husain, who entered the league as an undrafted free agent. “And so we used to always say, ‘Don't give them a reason to cut you.’ ”

By 2010, Husain was a frequent starter, and his Vikings training staff built him a meal plan to help get him the nutrients he needed while fasting—a far cry from what Olajuwon had experienced, back when teammates watched with concern. The support was a boon for Husain, but his fears continued. Without Olajuwon’s MVP pedigree, and in a conservative league that punishes deviation from the norm, it seemed reasonable for the brothers to wonder whether their fasting would cost them their careers.

In time they’d find the limits of the league’s tolerance. The practice of Islam is built on five pillars: profession of faith, prayer, charity, fasting during Ramadan and Hajj, the pilgrimage to holy sites in Mecca and Medina, where millions of Muslims travel each year. Each Muslim is to complete the trip once in their life. And in 2012, the Abdullahs felt their calling.

As soon as the brothers stepped away from the NFL they were criticized for abandoning their teams. Husain knows the choice might have looked confusing—Why not wait a few years, until after your playing days are over?—but as he tells it, it wasn’t a decision so much as a duty.

“How do we know we're gonna be alive tomorrow?” Abdullah remembers thinking. “Allah says: ‘If you walk towards me, I will run towards you.’ And Hamza and I were like, ‘O.K., well, Bismillah. [In the name of Allah.]’ ”

For Husain, that pilgrimage cost him a year of football, but he played three more seasons with the Chiefs. For Hamza, the cost was higher. He waited by his phone and eventually fell out of touch with his agent. “My faith shouldn’t be a burden,” he told The Undefeated in 2018. “It’s an asset.”

Even as Husain’s career continued, though, he faced unfair scrutiny. During a home game in 2014 against the Patriots he tracked an errant Tom Brady pass over the middle and sprinted 39 yards through tacklers for a touchdown. Afterward, he slid through the endzone on his knees in celebration before dropping his head down in prayer. Everyday stuff. Only, when he looked up, he’d been assessed an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty.

Broadly speaking, church and the NFL are synonymous. It’s not quite a joke to say that they share the sabbath. Tim Tebow, among others, made a brand for himself by falling to a knee in prayer. In Kansas City, Husain spoke with the referee after the call, and the league admitted the next day that it was a mistake to penalize him for praying. Seven years later, he says he doesn’t remember what reasoning the official gave; he can’t say for sure why he was flagged.

Says Abdullah: “I’m not the judge of men’s hearts.”

I often wonder about the role that September 11 played in my own life. I had lived in a post-9/11 world for just under a decade when I decided that I didn’t believe in God, and it wasn't long after that I shared my lack of faith with my parents. It was difficult. They were hurt—not because I’d betrayed them, but because I’d declined a part of the life that they’d bestowed upon me.

I think about how things might’ve been different if I hadn’t grown up where I did, in a particularly Muslim-spooked part of the Midwest; if there had been other Muslims at my school; or if I’d been a few years older, or a few years younger, on 9/11. My sister was just two years behind me in school. We shared carpools and teachers and after-school clubs—in so many ways, the same experience. But she was too young to process the immediate wave of vitriol that followed the attacks. I had cousins my age who were still in their formative years when the towers fell. But they lived in Pasadena, and they went to school with friends with names like Osman and Osama. They stayed devout.

In middle school I walked from class to class expecting to be called a terrorist with frequency. I don’t know whether things would have been different if I were raised alongside peers who learned more than two verses of the Quran (which is about all I can still recite from memory), or in whom I could have confided my anxieties and fears. Maybe I’d still be practicing. Or maybe 9/11 was a catalyst for something that would always, eventually, happen inside me.

I was able to escape the sort of torment that continues to befall Muslims because I don’t look Muslim or sound Muslim. Back home in Michigan, I can blend into a crowd in my predominantly white community, a skill I worked hard for.

I didn’t want to be like my Christian classmates. This was not a metamorphosis conceived of jealousy. It was a subconscious choice between being someone who would face overwhelming scrutiny for a lifetime and someone who wouldn't. But thanks to Muslims like Muhammad, Abdul-Qaadir and the Abdullah brothers, and those who followed in their footsteps, that’s not a decision the next generation necessarily has to make.

“This is who we are,” Muhammad says. “We’re not going to change parts of who we are to make ourselves more palatable for anyone.”

• The 9/11 Story That Inspired Tom Brady

• Colin Kaepernick Went First. They Were Second

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn