The 26-year-old computer wiz who propelled Raiders to SBXVIII title

As part of our countdown to Super Bowl 50, SI.com is rolling out a series focusing on the overlooked, forgotten or just plain strange history of football's biggest game. From commercials to Super Bowl parties, we'll cover it all, with new stories published every Wednesday here.

Whoso pulleth out this sword from this stone is rightwise King born of all England.

—“Le Morte d’Arthur,” Sir Thomas Malory

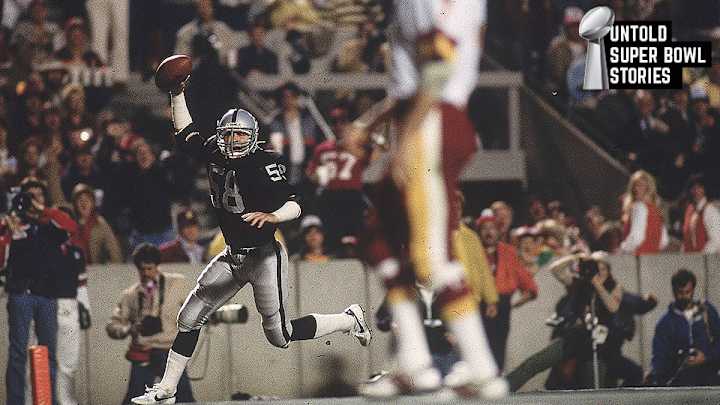

On Jan. 30, 1984, Sports Illustrated featured on its cover Jack Squirek, a backup linebacker for the Los Angeles Raiders, jogging across the goal line, holding a football high above his head. In the foreground, Redskins quarterback Joe Theismann stared from across the field. And between the Super Bowl XVIII opponents: the words Blowout! and Jack Squirek Shocks the Redskins.

Squirek made the play that cemented a 38–9 Raiders blowout—”Black Friday” they called it—but someone else pulled the magic sword from the stone and presented it to him. It wasn’t Oakland coach Tom Flores. And it wasn’t Charlie Sumner, Flores’s defensive coordinator. No one has ever told the real story of the play that sealed the Redskins’ fate in Tampa Bay, of a seemingly enchanted feat by an unlikely boy hero.

*****

With 12 seconds left in the first half, facing first-and-10, the favored Redskins (who’d won the previous year’s Super Bowl and then came back and pretty much dominated on offense and defense all over again in 1983) had the ball at their own 12-yard line, trailing the Raiders 14–3. But instead of telling Theismann to take a knee and regroup in the locker room, Redskins coach Joe Gibbs called “Rocket Screen.” In his defense, Rocket Screen seemed a sure winner. Gibbs had used Rocket Screen in an eerily similar situation earlier that season: Trailing the Raiders by 15 and pinned deep in their own territory, Theismann hit backup running back Joe Washington for 67 yards. The Redskins scored a touchdown three plays later and eked out a comeback thriller, 37–35 .

That much you’ve heard, though. This is the part you haven’t.

Just before halftime of Super Bowl XVIII, as the Redskins’ offense took the field on the fatal drive, John Otten—the Raiders’ then-26-year-old computer operations coordinator, who’d begun his tenure as a ball boy at the age of 11—was standing on the sideline next to Sumner. And at that moment he saw what no one else saw, so he spoke up. His exact words, as he recalls them: “Here comes Joe Washington. Charlie, I think they’re going to throw a screen. Last time we played them they threw a screen in this situation.”

Sumner asked, “Are you sure?”

“Yeah.”

“As soon as I saw Joe Washington come [on the field] I knew—or at least I had a feeling,” says Otten, who still works for the Raiders today. “It wasn’t the exact same situation, but it was close enough that it sparked my memory.”

What, pray tell, could possibly have emboldened this assistant to overstep his boundaries and pipe up, though? Explains Otten: “Because it was so late in the half, our assistants were already on the field—they came down from the coaches’ booth. I knew we wouldn’t have anyone upstairs.”

Bud Bowl: The novel idea that forever changed Super Bowl commercials

Equally amazing is the fact that Sumner listened. Otten, in fact, had always stood next to Sumner during games, feeding him information, and after Otten made his prediction, Sumner invented a defense on the fly: Cover Three Lock Joe. (In other words, lock up Joe Washington.) Sumner yelled over to Squirek, who was standing on the sideline around the 30-yard line. “Come here!” he ordered, grabbing Squirek by the shoulder pads. “I’m going to have you cover Joe Washington man-to-man. We’re going to a zone prevent. Don’t do anything stupid, like go for an interception and miss a tackle and let Washington get a big play on us.”

Squirek promised he wouldn’t do anything stupid, like go for an interception.

Matt Millen, the Raiders’ star inside linebacker, was on the field at the time and had already called another play when his coaches started yelling at him to come out, but he couldn’t hear them. When Squirek ran onto the field, Millen stared at him, totally confused. “Charlie wants you out,” Squirek said.

“Matt Millen was furious,” recalls Flores. “He was yelling and screaming on the sideline. Matt never liked to come out. Very emotional guy.”

“I was pissed off,” Millen admits. “I could have expressed myself in a little different manner.”

“I’ll never forget,” says Otten: “Matt went over to Charlie on the sideline. Charlie was doing little hand signals like he was making some big blitz call; Charlie was really good at masking what he wanted to do. And I remember Bubba—that’s what everyone called Millen—comes over to him and asks, ‘What are you doing, Charlie?!’ And I said, ‘Hey, Bubba, just relax. Everything is going to be fine.’ ”

*****

The play unfolded quickly.

Squirek saw the Redskins break huddle from the sideline and sprinted onto the field late. He was nervous. He wanted to get in a good position because Joe Washington was quick, but he was just getting set when Redskins center Jeff Bostic snapped the ball.

Theismann casually dropped back, a confident five-step drop, the whole time looking to his right, away from Washington and Squirek, trying to deke the Raiders by looking one direction before throwing the other. Theismann’s fake fooled no one, though. Certainly not the young video coordinator on the sideline. “The way he started to drop back, I knew it was a screen pass,” says Otten. “I’m looking at it and I’m going, Oh, this is going to be good.”

After pretending to be a blocker for a few seconds, Joe Washington sped out of the backfield to his left in order to receive the pass. But Raiders defensive end Lyle Alzado saw Washington leaking out and pushed him back and off his course, leaving the tailback seven yards behind the line of scrimmage.

Theismann, meanwhile, spun to his left while still backing up and threw the screen pass off his back foot. (“I think Joe threw it blindly,” says Flores, “and I thank him for that. I thank him every time I see him.”) As the ball floated through the air, Squirek reacted, ignoring his coach’s instructions not to go for the pick. He saw the ball, grabbed it, jogged exactly three steps and was in the end zone. Game essentially over. After the play Squirek remembers a dozen teammates jumping on him while he thought, simply, Wow, I just made a big play in the Super Bowl.

Millen, who had been fuming on the sideline, hoisted Sumner over his head, kissing him. “Who cares how you win?” Millen says now. “When I think back on it, Jack was better for that job than I was. Jack had better cover skills than I did man-on-man. It was a perfect move.”

After the Raiders kicked the extra point to make it 21–3, Sumner looked over at Otten, pointed and mouthed the word, “Thanks.” In the locker room at halftime the two men spoke excitedly about the play. And then they kept the details secret the rest of Sumner’s life.

Sumner died in Maui on April 3, 2015 due to complications from gall bladder surgery. He was 84.

*****

Squirek was in on the secret. “Oh, yeah,” he says. “We’ve talked about it over the years.”

Millen didn’t know. Told recently that Otten had called the play, Millen pauses briefly, then says, “That doesn’t surprise me. Johnny O, he could do anything. He shot film. He taped guys. He was like MacGyver. Johnny O wouldn’t be shy about telling Charlie what he thought.”

The scabs who paved the way for the Redskins’ 1987 Super Bowl title

What about Flores? “To be honest with you, this is the first I’ve heard of that,” he says 31 years after the fact. “I was never on the phone during games, so I didn’t hear all the interaction from sideline to press box. But it doesn’t surprise me.”

That’s because Flores trusted his coaches and he trusted Otten. It was Flores, in fact, who had discovered Otten, identified him as a talent when Otten was just a ball boy and Flores was a Raiders assistant under John Madden. Back then, Flores (a former NFL quarterback) and Otten (a high school QB at the time for Bishop O’ Dowd High in Oakland) would play catch. “But he wasn’t just there to be a ball boy,” says Flores. “He was there to contribute.”

And then he nearly wasn’t. In 1978, “John Madden’s last year, [Otten] quit and he was going to work for the Baltimore Colts as an equipment guy,” recalls Flores. “When I became head coach, one of the first things I did was talk Johnny into coming back. I said, ‘I don’t want you to be just a gofer; I want you to be in charge of our computer program.’ We weren’t using computers at the time. So I sent him to school to learn computers. He became an integral part of everything. ... We’ve been friends ever since. He still helps me—he helps me with my little iPad.”

At 58, Otten’s job title with the Raiders now reads IT/Video Coordinator; it’s his job to make sure Oakland’s scouts all get the video they need. For years, he had no idea Flores fought to hire him—not until Flores told him, just after Al Davis’s death, in 2011. The Raiders keep secrets well.

All Otten knew was that the day the Raiders hired him to keep him from Baltimore, he got a call from Davis’s secretary, Bev Swanson: “Mr. Davis would really like to talk to you.”

“He doesn’t even know my name,” Otten told Davis’s secretary.

On that he was wrong, and when the two men met in the training room Davis asked Otten why he would possibly leave for the Colts.

“Because,” Otten explained, “I’ve been a ball boy and working in equipment here for 10 years. I just didn’t think anything was going to happen.” Keep in mind, Otten was 21 at this point.

“F--- Baltimore,” Davis said.

“OK,” Otten said. “What do you want to do?”

The two men haggled—Otten told Davis that he was getting $1,000 a month from the Colts; Davis offered $500—and finally settled on Davis’s figure, plus a car, insurance and a pension.

So did Davis ever know the truth, that six years later his young hiree was the one who, in effect, sealed Super Bowl XVIII? “My guess,” says Otten, “is that if he knew he would have said something; we had a really good relationship. But no, he didn’t know.”

So Johnny Otten pulled the sword from the stone and helped win a Super Bowl for the Raiders. And Al Davis, wizard that he was, never knew. There’s something mythical about that.

Camelot.