Olympic Training Towns: Fort Benning, GA.

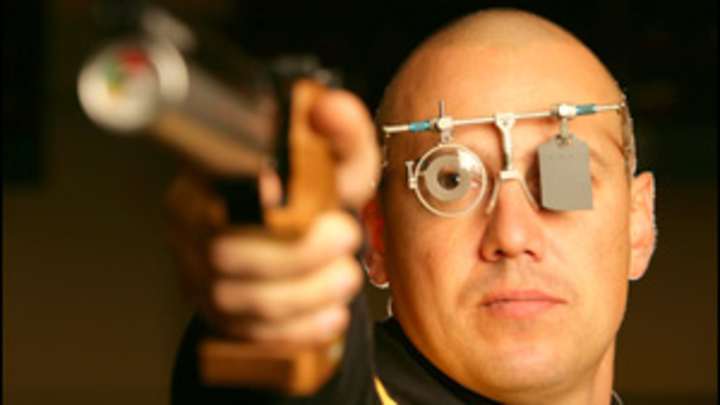

Just off U.S. 27, five miles east of the Georgia-Alabama border, lies a 182,000-acre self-contained slice of Pleasantville, where moms wait on porches behind white picket fences for school buses to drop off their kids. This picturesque community of about 35,000 is in many ways a typical small town, with a grocery store, a gas station and a thrift shop, but the similarities go only so far. Fort Benning, located within Columbus, Ga., is the nation's second-largest Army post. About 18% of the city's residents live on post, and among the soldiers are 32 shotgun, rifle and pistol shooters -- men and women, ages 19 to 45 -- who are part of the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit. They are the most eagle-eyed and granite-nerved of all prospective Olympians.

The team members are held back from combat to bring the military glory through sports. Since the unit was formed in 1956 by President Dwight Eisenhower to improve the Army's shooting proficiency, its members have won 40 world and 22 Olympic medals. Physical training starts at 8 a.m., when shot and rifle teams begin their workout with squats and crunches. They wear identical Army T-shirts, black shorts and sneakers. Soon, across seven ranges that cover 260 acres, a crackle of gunshots breaks the morning calm and the scent of damp grass carries a hint of what smells like freshly lit matches. Most of the athletes come from hunting backgrounds -- handling guns since they were seven or eight -- and were recruited by the Army just to be in the unit. "When I first started shooting as a kid, I told my dad I wanted to go to the Olympics," says Vincent Hancock, who won the world skeet title in 2005 at age 16. "And I've been shooting for that ever since."

There is some time to kick back -- say, during a trip to the Four Winds restaurant, which serves a one-pound Sniper Burger -- but not for slacking off. The stakes for poor performance can be high. Those at the bottom, about 20% each year, can be dropped from the program, placed into what the shooters call Big Army and are likely to be sent abroad.

Yet few soldier-athletes fear assignment. Rob Harbison, now a lieutenant colonel, left during the 1991 national championships when he was called to join operation Desert Storm in Kuwait. "We're soldiers first," says Harbison, a '96 Olympian in air rifle. "It was what I signed up to do." It is a typical display of frankness in a place where you can always find straight shooters.