The Curious Case of the Electrified Épée

The phone call comes at the supper hour. A Ukrainian number. The voice—speaking Russian—is polite, formal, unwavering.

“Would you be ready to meet with us?”

“No.”

“So you do not want to?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Why? Because it is painful to talk about?”

“It’s a painful wound for me. I don’t want to trouble myself, and you as well. I don’t want to exculpate myself. I don’t want to talk about who I am, bad and good. I am very thankful for your care, but I refuse to cooperate with you.”

The man is old now, 83 in September. He will not trudge a winding staircase to his personal attic and rummage through the lock box of memory, brushing cobwebs off a sultry, long-ago July morning to offer a why or a how for your benefit. He seeks neither your comprehension nor your absolution. He will offer no remorse or penitence. He will make no effort to place the day in context, to frame the event in the whorl of his times.

The story is dead. After 40 seconds, the conversation is dead.

“Всего хорошего,” he says. “Всего хорошего.”

All the best. All the best.

And with that, the greatest cheat in Olympic history hangs up.

***

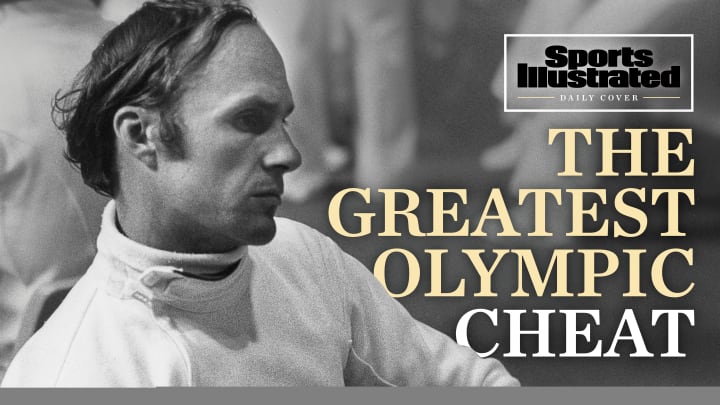

Seven a.m., July 19, 1976. The athletes’ bus from the Olympic Village is snaking six miles southwest to the Université de Montréal as unlikely seatmates conduct business. They are of different cultures, of different countries and of different stature in their sport, modern pentathlon. Andy Archibald, Great Britain, is a team alternate. Boris Onischenko, Soviet Union, is a titan. He has won a world championship and an Olympic silver medal and been part of gold-and-silver-medal-winning Olympic teams. These men do have one thing in common, the basis for the transaction: They are left-handed, which, as the day unfolds, will be a significant detail.

Archibald particularly admires the custom-designed orthopedic grips of Onischenko’s épées. Through the years Archibald has been a reliable customer. Western pentathletes buy their own swords while the Soviets, mostly military men, have theirs supplied. So instead of paying 15 pounds sterling for a sword, Archibald can spend perhaps a third of that for a used Onischenko épée. Win-win. In rudimentary German, a shared language, the seatmates strike a deal, agreeing to finalize it at the conclusion of the five-day event.

This is the second day of competition. Of the five disciplines—riding, fencing, shooting, swimming and running—this sweltering Monday should belong to Onischenko. No pentathlete wields his épée with more skill or intent. A century earlier, when fencers were bound by honor instead of electric circuitry and body cords, Alexandre Dumas or some other ink-stained romantic might even have called him a swashbuckler.

By the end of the week he knows he will no longer need those swords. Onischenko turns 39 in two months and has scraped onto the team for Montreal, his third Olympics, but he will be long retired when the Games come to Moscow in four years. This will be a final grab for an individual Olympic title that will be worth more than its weight in gold. A victory will secure a promotion in the MVD, the Interior Ministry, where he holds the rank of captain, and likely lead to the perks that go to Olympic heroes: a bonus, better housing, a more comfortable future in the USSR.

At 8 a.m. on Piste E, the Soviets begin fencing against their countrymen. In one bout Onischenko faces Pavel Lednev, the reigning three-time world champion and the favorite for individual gold but not Onischenko’s equal with a sword. At the USSR Olympic trials, Onischenko had won the vast majority of his bouts. “I fenced him six or eight times over the years,” says Mike Burley, an American pentathlete who placed 16th in the 47-man field in Montreal. “He always cleaned my clock. I was always hoping to get lucky, but against a guy like him you don’t get lucky.” Onischenko wins both intrasquad fights. At 8:45, bouts start against other nations. Great Britain is first.

Onischenko’s initial opponent is Adrian Parker, another lefthander. Onischenko lunges, and the light signaling a hit goes on. (A hit, scored when the tip of the épée is depressed, closes the open electrical circuit by making contact between the two wires that run the length of the sword to the base inside the bell guard. The circuit continues from a plug near the handle through the body wire in the fencer's jacket, through the electric spool, and to the scoring box, which triggers a red or green light to indicate who scored the hit.) Fight over. Onischenko’s touch seems too good to be true, at least to Parker. He removes his mask and protests to referee Guido Malacarne that he hasn’t been hit. Following a cursory examination of Onischenko’s épée—all swords must pass inspection before competition—the referee does not annul the touch.

“Adrian was pretty grumpy,” says Mike Proudfoot, the Great Britain team manager who estimates he was less than two meters from the piste. “But at that point my job was not to let it affect Fox.”

Jeremy Fox—known as Jim to everyone but his mother—is Britain’s fair-haired, blue-eyed boy, the very model of the modern modern pentathlete: worldly, mannered and James Bond handsome. He is held in the highest regard inside the sport and out. Fox possesses a singular gift, the ability to talk to royalty or rogues and make everyone around him feel special. “One of his favorite expressions was ‘it takes [no] effort to be nice to people,’” Archibald says. Fox, a four-time Olympian, has fenced Onischenko often, notably at the 1972 Games, when Onischenko took the silver medal and Fox placed fourth. Four years later their dance begins anew.

Modern pentathlon épée bouts end with a single legitimate hit or after three minutes if there are no touches. Fox and Onischenko are 40 seconds from the end—both will be assessed a loss if no hit is scored—when Fox lures Onischenko into an attack. In Richard Cohen’s 2002 exhaustive history of fencing, By the Sword, Fox describes the finish this way: “I was still outside hitting distance when I picked up Onischenko’s blade—really high, before his blade was anywhere near me. His blade was above my head. And I smacked [my point] into his chest, but the light was already on [against me.]” The hit is implausible at best, physically impossible at worst. At the instant Onischenko’s touch registers, the tip of his épée is pointing skyward.

“We hadn’t started yet, so we’re watching their match,“ Canadian pentathlete Jack Alexander recalls. “We’re sitting next to our coach, [Joe Bucsko], who was a real exaggerator. The light goes on and he says, ‘Boys, Onischenko’s so fast you couldn’t even see it.’ And all three of us are going, ‘Coach, he didn’t touch him.’ ”

Malacarne, who later would say he was paying closer attention to Onischenko after Parker’s protest, instantly reaches the same conclusion and annuls the hit. Onischenko does not object. “He apologized straight away,” Proudfoot says. “Sorry. Sorry, Jimmy, I’ll change my weapon.” Fox is not assuaged; merely swapping épées might allow Onischenko a chance to use the same one later to score more dodgy hits. As Malacarne tells Cohen in By the Sword, the Soviets actually produced a different épée for closer inspection—an impromptu game of three-sword monte. Despite the pantomime—Soviet team members deny there was any trickery—Malacarne seizes the correct épée. He summons the appeals jury to the piste to examine it. An hour later a public address announcement says Onischenko’s sword was found to have been faulty, and his score would be docked a trivial number of points.

The British team considers the penalty a slap on the wrist, which, in its view, is more contact than Onischenko ever made with Fox or Parker. Proudfoot begins writing an official protest by hand to argue that Onischenko’s faulty sword constitutes deliberate cheating, which should result in disqualification. At 10:40 he files the protest to the governing body, the Union Internationale de Pentathlon Moderne. A $25 filing fee is attached. The Montreal Games will become notorious for their staggering cost overruns, but 25 bucks is a wise investment even if the merciless gaze of a young fencing enthusiast already had detected chicanery. Twelve-year-old Nicholas Bacon, who is awaiting surgery for a brain tumor, has been watching the British matches intently. He turns to the woman seated next to him, a family friend, and announces that Onischenko is cheating. The woman, Bacon’s hostess, is Mary Glen-Haig, a formidable figure in fencing, a daughter of a 1908 Olympic fencer, a four-time Olympian herself and a future member of the International Olympic Committee. She pulls rank. Glen-Haig strides towards the pistes and collars the head of the fencing competition, telling him confiscation of the sword and a point deduction are insufficient penalties.

Voilà, les jeux sont faits. The officials who removed the sword discover a break in the grip’s insulation, although initially they can’t determine whether the cut has been made deliberately. But Glen-Haig’s blunt intervention has unsettled the modern pentathlon officials. The head of the International Fencing Federation, a Belgian named Charles Debeur, arrives to personally dismantle Onischenko’s épée. His inspection reveals that this is a matter of engineering, not happenstance.

A hole has been drilled in the grip, which has been covered by a snug-fitting chamois cloth. Inside the custom-made grip is a metal button. Onischenko simply has to press the button with fourth and pinky fingers to close the electrical circuit, turning on the light. No touch required. He can register a hit with impunity and conserve energy for the next three days of competition. In the one-page judgment of the jury d’appel, which includes Debeur, the rigged épée is “incontestablement un cas de fraude.” The smoking sword.

Sandy Kerekes, a Hungarian-born Montrealer, is the modern pentathlon competition director. The scene is preserved in his mind’s eye: He walks into his cramped office, and the three-member jury d’appel is seated in front of him. The sword, its grip laid bare, rests on a table. Onischenko is to his left. “He is almost collapsed in his chair as if the world had collapsed around him,” Kerekes says. “This was shame in front of the world. All the questions were asked. He never answered one. He claimed innocence.” (According to By the Sword, Onischenko later argues the rigged sword isn’t his, an alibi that stretches credulity like it’s taffy. Remember, he is left-handed. Every other member of his team, including alternate Vladimir Shmelev, is right-handed.) Kerekes again: “Calculated cheating. In athletic terms the crime he committed was a total murder.”

In accordance with the UIPM Rule book of 1974, articles 3.121 c, 1.36 and 1.37, Onischenko is disqualified. His name is removed from the venue scoreboards. Around 12:30, Alexander, the Canadian, steps into the hallway in time to see Onischenko hustled off by Soviet officials.

Proudfoot describes the exit similarly: “On this very hot day two guys appeared looking like what we thought of as typical KGB stooges. Two guys in trench coats and droopy hats. They took him by the elbows and removed him from the arena.” Onischenko’s swash is buckled.

Tuesday morning, July 20, a fencing story, apparently for the first time in its history, runs on A1 of The New York Times. Imagine. Twenty-four hours earlier Onischenko had been obscure, a champion whose triumphs in an anachronistic sport were recorded in agate type. Now he is a front-page fraud. A punch line. He quickly will be nicknamed Boris Dis-Onischenko because low-hanging fruit is the most tempting.

***

Last Feb. 25, the day an old man in Ukraine returns a Sports Illustrated call and firmly declines an interview, the IOC announces sanctions against Albanian 200-meter runner Klodiana Shala. In a retest of samples from London 2012, Shala’s came back positive for Stanozolol.

Stanozolol is an old-school anabolic steroid that crashed the Olympic lexicon in Seoul 1988, the wind beneath the wings of Ben Johnson, who had run 100 meters in 9.79, faster than any man before. Johnson’s failed doping test is often considered the biggest Olympic scandal because it occurred after the most anticipated event of the 17-day carnival, his showdown with Carl Lewis. This, of course, doesn’t make Johnson the greatest Olympic cheat—merely the most memorable. Six of the eight men in that race would be linked to PEDs. In future Summer Games, doping disqualifications would become depressingly common, primarily in athletics, which accounted for roughly two-thirds of the positive tests in London. In a more trusting time, Johnson’s positive drug test evoked shock and, in Canada, soul-searching in the form of a government inquiry into steroids in sport. After the incessant thrum of Balco and Lance Armstrong and Russia’s state-sponsored doping, the Seoul scandal is greeted three decades with a sad, knowing nod. Big Ben, greatest five-ringed cheat? Please. Cycling through PEDs doesn’t require much more than a supplier, a syringe, a protocol and a cracked moral compass.

Onischenko’s scam, on the other hand, was ingenious. He had moxie. He, or some devious helper, had a grasp of electronics. His guile could make a 2017 Houston Astro blush. Onischenko put the skull in skulduggery.

“It was unique,” Olympic historian Bill Mallon says. “Almost all the other cheating has been related to PEDs. There were some gender identity things at the [1936] Berlin Olympics and in the early ’60s, but nothing with rigged equipment.”

If memory of Onischenko’s ruse has faded with the years, it’s because his is a sport that hides in plain sight. While other Olympics sports vanished or went on hiatus—adieu, tug-of-war; grab some bench, baseball—modern pentathlon has just sort of been a face in the crowd. The modern Games began in 1896; modern pentathlon has been on the program since 1912. If that inaugural competition is noteworthy, it’s only because the USA featured a brassy West Pointer named George S. Patton Jr., who placed fifth primarily because of a poor shooting performance; Patton would wind up on the podium in World War II.

Curiously, Pierre de Coubertin, creator of the modern Olympic movement, also founded modern pentathlon. (As father of an aggregation of military-type sports, de Coubertin is less James Naismith with peach baskets than Arianna Huffington with websites.) Modern pentathlon replicates the actions of a 19th-century French courier who rides, fences, swims, shoots and runs to deliver his message. (In his Modern Pentathlon, a Centenary History: 1912-2012, Archibald writes that de Coubertin originally favored rowing over shooting.) Modern pentathlon never realized de Coubertin’s grand vision of its champion being hailed as the ultimate Olympian, but in 2013 the IOC confirmed modern pentathlon—now streamlined to one or two days—as one of 25 core sports, at least through Tokyo 2020.

For all its relative anonymity, Olympic modern pentathlon offers another notable breach of propriety, one that predates Onischenko’s. The solecism occurred in Mexico City 1968, one year after the IOC introduced drug-testing protocols. Apparently to calm his nerves before the pistol shooting, Hans-Gunnar Liljenvall knocked back a couple of beers and tested positive for excessive alcohol, earning the dubious honor of being the first Olympian disqualified for doping. Compared with tampering with an épée, being turfed for a few brews seems overzealous. Liljenvall, a Swede, simply was putting the skol in skullduggery.

***

The 12-hour day at the venue is done. They are gathered in the British team room at the Olympic Village, marveling at the events of the morning, trying to make sense of a fencing fever dream. Fox is taking it particularly hard. He respects Onischenko and assumes the feeling is mutual. The rigged sword has rattled him. Fencing poorly, Fox ties for 18th on the day and now offers a sweeping apology. He says he likely has deprived Great Britain of a team medal. He announces he will consider dropping out.

At 10 p.m., there is a knock at the door. Surprise visitors. Pavel Lednev and Vladimir Shmelev.

They are friends with the British athletes, or at least something as close to friends as the ’70s Iron Curtain permits. Over the years the Soviets have introduced Fox to vobla—salt-cured fish—and Fox has bought Shmelev jazz records. Ella Fitzgerald. Louis Armstrong. They now apologize for the scheming Onischenko. “[Onischenko] had a reserved character,” Shmelev tells SI. “Like a lone wolf. Always alone, alone, alone.” When asked last May about the substance of the meeting, Shmelev says he and Lednev denied any knowledge of the crooked sword and told the British team that they were being allowed to remain in Montreal to compete individually.

Proudfoot recalls the conversation, conducted in English, as more revealing. “They were actually pleased with what had happened to Onischenko,” he says. “They said he had been reporting everything they did back to the authorities. This was the middle of the Cold War. And they had been doing black-market trading during their travels outside the Soviet Union. Caviar. Cameras. Stopwatches. They suspected Onischenko had [cheated] before. They commented on how well he had done at the USSR trials and that maybe he had been trying out his magic device then. … They seemed eager to disassociate themselves from Onischenko’s cheating. They were very keen to exculpate themselves.”

After 20 minutes the visitors leave. Two days later at the Olympic pool, Fox and Shmelev discuss Onischenko again. As a token of fellowship, Fox hands Shmelev a memento. “We didn’t have those types of things,” Shmelev says. “And they had these blue towels that said ‘Great Britain Modern Pentathlon.’ I still have that towel.”

***

The two men in the trench coats and droopy hats escort Onischenko to a Soviet ship docked in the port. He is confined to a cabin. Onischenko is front-page news in the Times, but the Montreal Gazette, seduced by Nadia Comaneci’s historic 10s, plays his caper on the seventh page of its Olympic coverage. The following day he is about to be stripped of his Soviet sporting honors, but he earns a promotion in the Gazette, to Page 3. An eight-paragraph story quotes an unnamed USSR official saying cheating is “a very sad matter.” The official adds, “The team did not know about it. The trainers did not know about it. It is a tragedy for the entire team. These are not our methods.”

The oft-repeated version of Onischenko’s next few days: He flies to Moscow, where Communist Party leader Leonid Brezhnev dresses him down, strips him of his rank and fines him 5,000 rubles. The details are mere curlicues to the script of the story, writ large in the West. “This affair,” Archibald says, “was wonderful propaganda.” Seven years before Ronald Reagan’s Evil Empire speech, at the height of a surrogate war being fought, in part, with games instead of bullets, Onischenko fit the tidy narrative: the duplicitous USSR and its East Bloc underlings vs. the noble U.S. and its upstanding allies. After Ben Johnson and so many other sporting scofflaws, dirt will be spattered practically everywhere. Not in 1976.

Rumors fly about Onischenko, beginning that afternoon in Montreal. They will for years. The most repeated has Onischenko being found dead, floating in a Moscow pool.

The truth is less le Carré. Onischenko doesn’t drown. He doesn’t kill himself. And he never is far from public view, at least in his hometown of Kiev. Several years after the Olympics, he attends the Soviet modern pentathlon championships there; Lednev and Mosolov spurn him. In 1985, Martin Dawe, a British pentathlon official, spots Onischenko in the crowd at the world junior championship in the city.

So what was he doing? Reportedly he was an athletic administrator. An August 2005 story in a Ukrainian newspaper, Ukrayina Moloda, mentioned that Onischenko had been heading the Atlet sports base since its founding 28 years ago, a facility located on the grounds of the Olimpiyskiy National Sports Complex in Kiev. Five years earlier, on a BBC 5 radio program that aired Christmas Day 2000, its correspondent reported that Onischenko said he was working in a sports training facility, teaching fencing. (The name of the series airing the Onischenko segment was Scandal!). The correspondent also mentioned Onischenko inquired about Jim Fox.

Three years earlier, in 1997, Fox was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He now lives in a residence, which is under quarantine because of COVID-19. On March 5, before the lockdown, 79-year-old Jim Fox, MBE, OBE, a recipient of the Olympic order, meets British modern pentathletes at their training center in Bath. Fox finds speech difficult on many days and was unavailable for an interview although Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) Stuart Cowen, a friend, says, “Jim was devastated. He just thought Onischenko’s kit was a bit faulty. Jim told me, ’He didn’t need to cheat. He was the best fencer in the world.’”

***

No how. No when. No why.

There are gaping holes in this story of the greatest Olympic cheat. Maybe he masterminded and executed the caper himself. It seems probable but not provable that he had an accomplice. He could have been practicing his dark arts for months if not years. Or maybe he debuted his con on a pit-stained Monday in Montreal. Only Onischenko can say with certainty, and he will say nothing. No exculpation, no explanation.

Into the void, conjecture rushes in.

Mike Proudfoot: “The simple explanation is that he had achieved everything except [an individual] Olympic gold medal. This was his last chance.”

Andy Archibald: “This was a last desperate stab for immortality.”

Sandy Kerekes: “It had to be his own ego and materialism.”

Mike Burley: “Those guys from the Eastern Bloc would be pretty much set for life if they won a gold medal. The bottom line is it was so much more important to the guys on the other side of the wall.”

Proudfoot and Archibald share the opinion that Onischenko likely first used the rigged épée in Montreal if for no other reason than he bungled the job so badly. Diabolical in design, Mr. Bean in execution. Onischenko could register a hit at will, but inept timing beggared belief in the touches. Maybe he choked under Olympic pressure, but a more practiced trickster wouldn’t have pushed the button with his sword pointed skyward. On the biggest stage, Onischenko was as convincing as the schoolboy who signs a failing report card “My Mom.”

One man on the piste that day strongly suspects this was not Onischenko’s first time. He tells a darker tale. He is from the other side of the wall.

***

In mid-April as spring poked its head out, scanned the countryside and wondered whether it was safe to go outside, Boris Mosolov answers his phone. He is at his dacha north of Moscow, hunkered down with his cats and dogs. Mosolov is the other USSR pentathlete in Montreal, the third and youngest member of the team. He turned 70 in June, a man who carries a grudge as impressively as Russian soprano Anna Netrebko carries a tune. Forget? Hardly. Forgive? Not a chance. Mosolov recalls having to hide his accreditation to avoid hard glances and impertinent questions at the Village. How does that make an athlete feel? His teammates would achieve infamy or distinction—Lednev was inducted with the Modern Pentathlon Hall of Fame's inaugural class in 2016, six years after his death—but, unlike them, Mosolov would never win an Olympic medal nor compete in another Games. His Olympics turned to ashes.

During a 50-minute interview, Mosolov does the math. He calculates that if Onischenko had placed as low as 35th, the USSR still would have won the team gold. “I lost a lot because of it, materially and morally,” says Mosolov, who finished eighth. “The title of Olympic champion gives you a lot in Russia today—a pension and so forth. I’m stripped of all that because of him.”

Mosolov thinks the catalyst for the rigged épée was Onischenko’s failure to make the team for the 1975 world championships. The following summer, Montreal would be his last shot at an individual Olympic gold, assuming he qualified. Mosolov suspects Onischenko introduced the rigged weapon in April 1976 at a London event that counted in the selection process. But at the subsequent Soviet championships, before Montreal, Mosolov says Onischenko’s cheating was “unambiguously visible. People openly talked about it.” When confronted by competitors, Mosolov says, Onischenko was dismissive.

“The thing is I won the [Soviet championships] bout against him. He tried, of course. He knew who he was competing against,” Mosolov says. “[But] against second-rate athletes, he didn’t even beat around the bush. Whether he touched or not, the light would light up.… He was told about it. But he told everybody off. ‘I’m above that and that’s it.’ That’s how he was. Stubborn.”

Ultimately Onischenko’s mulishness might have contributed to his disqualification. Contradicting Western accounts, Mosolov says the weapon lay under a table as the fencing continued. “It was visible,” Mosolov says. “If Onischenko had said it was a rigged épée and it needed to be put away at all costs, theoretically Shmelev could have done that easily. If Onischenko had been a normal person, this is what would have happened. [But] he remained the asshole he was. He said everything’s fine. It’s clean. Although I know he was looking at that épée and seeing his own death.” As Russians are fond of saying, hope dies last.

So these are some answers to the how-when-why questions. One man’s answers, anyway. “Honestly, I think it’s even worse than doping,” Mosolov says. “With this button he deprived a competitor. It’s very revolting to me that a person resorts to that for the sake of his personal credo.”

In retrospect, Mosolov wonders whether seeds of the scam were planted even earlier. In 1972 Onischenko returned to Kiev a decorated Olympian, winner of the individual silver and the team gold for the USSR. His performance was splendid, but a fellow Ukrainian’s overshadowed it. Valery Borzov won the glamor events in Munich, the 100- and 200-meter sprints. He had international glory. Mosolov says, “Back home they hadn’t greeted him like Borzov. How can that be? I’m also an Olympic champion. I also have everything, but I’m not appreciated. That’s my opinion: He needed to be the most important [Olympian] in Kiev.”

***

Sandy Kerekes is 95. Over a Wiener schnitzel lunch at Foyer Hongrois in early March, a Hungarian seniors residence on the edge of downtown Montreal, he says he sometimes still dreams about Onischenko. Kerekes was nurtured in a prelapsarian sporting world and believes athletic competition—especially his sport—is meaningless if devoid of honor. Once Onischenko made the conscious decision to cheat, Kerekes says, “There were two ways for this to end. He could get caught. Or if he didn’t get caught and won, he would’ve been a total goddamn heel in his own head. This would have represented a downfall of a human mind. He would have lost his honor even if he would’ve been a hero for society and history.”

Honor, yes. That was ceded at the press of a button in an orthopedic left-handed grip. But Mosolov’s pension aside, not all was lost because the coda to this Olympic tragicomedy provides, in its way, a happy ending. Onischenko has no need for your forgiveness, because he received Fox’s long ago. “Jimmy forgave him,” says Dawe, the British official. “He felt Boris was under pressure to perform, which is what drove him to it.” Although disgraced, Onischenko is no international man of misery, seemingly having lived in relative comfort into old age. “They didn’t put him in jail,” Mosolov says. He laughs. “That wasn’t really done in practice, but they stripped him of all his titles. But no one can take that [1972 gold medal] from him. He’s an Olympic champion. And he’s still seen in Kiev as an Olympic champion.”

And there is this: Days after modern pentathlon stumbled onto the front page, Fox, Parker and Danny Nightingale took the team gold medal in a sizable upset. Win-win.

“Generally people in the sport don’t think evil of Onischenko,” Archibald says. “People understand the desperation of an act like that. He did get caught. He did get his comeuppance. But honestly the affair is viewed as something exciting. There’s a little Three Musketeers about pentathlon. The horse messenger galloping across the plain and all that. You need a little romance. It sells ourselves to the world.”

Special reporting by Gabrielle Tétrault-Farber.

Along with the pages of Sports Illustrated, you'll find senior writer Michael Farber in the Hockey Hall of Fame. Farber joined the staff of Sports Illustrated in January 1994 and now stands as one of the magazine's top journalists, covering primarily ice hockey and Olympic sports. He is also a regular contributor to SI.com. In 2003 Farber was honored with the Elmer Ferguson Award from the Hockey Hall of Fame for distinguished hockey writing. "Michael Farber represents the best in our business," said the New York Post's Larry Brooks, past president of the Professional Hockey Writers' Association. "He is a witty and stylish writer, who has the ability to tell a story with charm and intelligence." Farber says his Feb. 2, 1998 piece on the use and abuse of Sudafed among NHL players was his most memorable story for SI. He also cites a feature on the personal problems of Kevin Stevens, Life of the Party. His most memorable sports moment as a journalist came in 1988 when Canadian Ben Johnson set his controversial world record by running the 100 meters in 9.79 seconds at the Summer Olympic Games, in Seoul. Before coming to Sports Illustrated, Farber spent 15 years as an award-winning sports columnist and writer for the Montreal Gazette, three years at the Bergen Record, and one year at the Sun Bulletin in Binghamton, NY. He has won many honors for his writing, including the "outstanding sports writing award" in 2007 from Sports Media Canada, and the Prix Jacques-Beauchamp (Quebec sportswriter of the year) in 1993. While at the Gazette, he won a National Newspaper award in 1982 and 1990. Sometimes Life Gets in the Way, a compendium of his best Gazette columns, was published during his time in newspapers. Farber says hockey is his favorite sport to cover. "The most down-to-earth athletes play the most demanding game," he says. Away from Sports Illustrated, Farber is a commentator for CJAD-AM in Montreal and a panelist on TSN's The Reporters (the Canadian equivalent of ESPN's The Sports Reporters in the United States, except more dignified). Farber is also one of the 18 members on the Hockey Hall of Fame selection committee. Born and raised in New Jersey, Farber is a 1973 graduate of Rutgers University where he was Phi Beta Kappa. He now resides in Montreal with his wife, Danielle Tétrault, son Jérémy and daughter Gabrielle.