Auto racing goes for the green

The notion would have seemed absurd a decade ago but there, at the end of a national teleconference in June 2006, NASCAR chairman Brian France asserted his desire for his series to develop and race in the future something he called a "green car."

This from a fuel-chugging, globe-trotting, resource-consuming series that until last year utilized leaded gasoline, sent trailer trucks across the country 36 weeks a year with drivers and teams circumnavigating the same expanse in private planes.

Green and motorsports make for an odd combination, but there is no denying that the rising cost of gasoline has an effect on the sport's fans, many of whom drive hundreds of miles to see a NASCAR race.

Other racing leagues have made some progress in trying reduce their carbon tire tracks. Some, like the American Le Mans Series or the newly created carbon-neutral Jetta TDI Cup, are out to prove that the passenger car cousins of their race machines can be sexy-fast and easy on the conscience. The Indy Racing League, the first to utilize now-controversial ethanol as a race fuel, and Formula 1, which is scheduled to introduce ground-breaking technologies by next season, wished to underscore civic responsibility and how it can be married with technological advance.

"It's a much more difficult process than anybody even a year ago thought it would be," said Gary Nelson, former head of NASCAR's research and development center, "and that's because of the inefficiency of all the alternative fuels and the efficiency of the current fuels. I think a lot of people hung their hat on ethanol on the future.''

Alternative fuels were first seen as a cure-all but have since become pariahs. Embraced by governments as a means of reducing dependency on foreign oil and stimulating economies, latched onto by image-conscious series either to promote forward-thinking agendas (IRL) or manufacturers (like those in the ALMS) to show that their exotic cars could perform at high levels on alternative fuels -- so buy!buy!buy! and drive with impunity -- was the ideal of environmentalism as recently as a year ago. But scathing new academic reports, underlying the energy-intensive means of producing the corn-derived version of the fuel and its controversial links to deforestation and food-price spikes as land and crops are converted for fuel-production, have made ethanol a controversial and complicated subject. It is widely accepted that ethanol will now be a "transitional" fuel.

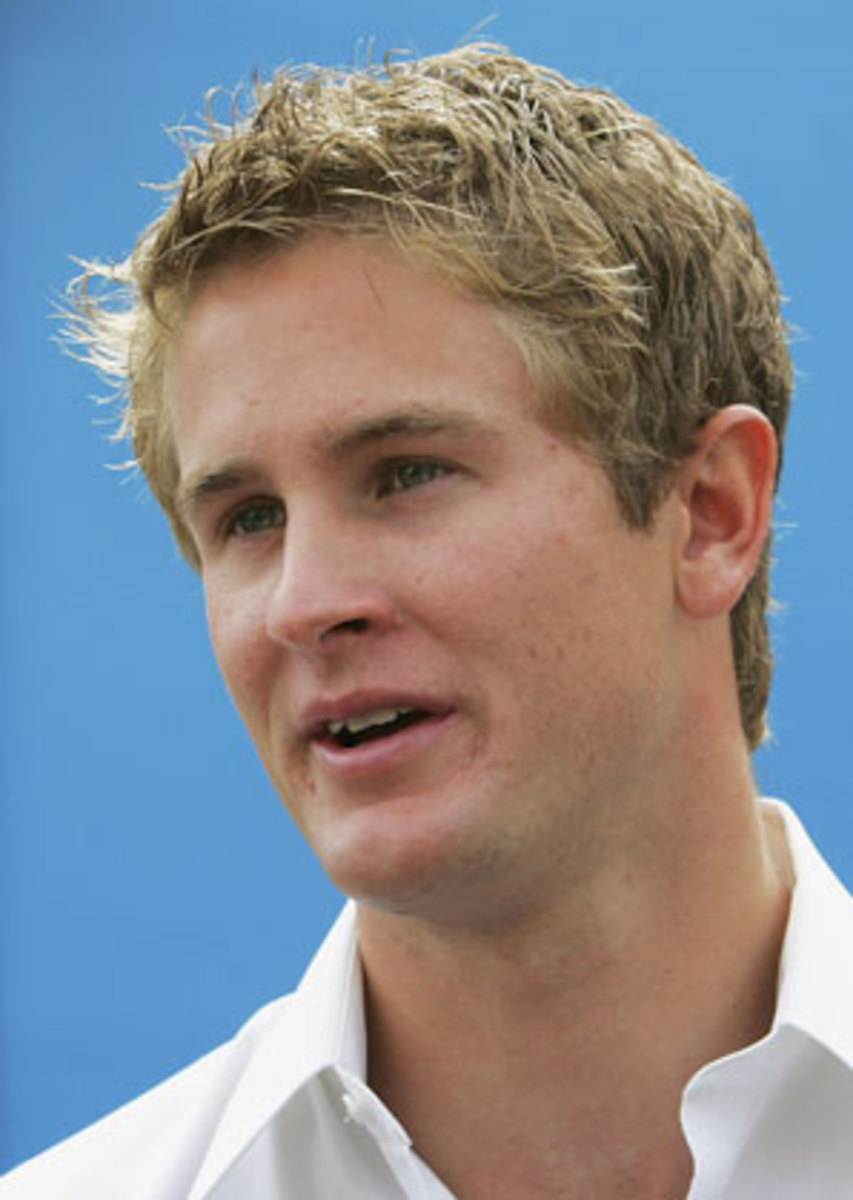

Men like Ryan Hunter-Reay, whose IndyCar sponsorship with the ethanol industry has made him a pitchman for the fuel, have been forced to field hard questions the last few months after previously taking nothing but softballs from the inquisitive.

"[People] don't get the whole story," he said, pumping reduced-price ethanol-blended gasoline at a promotional event before the Grand Prix of St. Petersburg on April 6. "[Time magazine] says, 'the amount of corn it takes to fill up an SUV can feed a child for a year,'' or something like that. "Well, the corn we use to make ethanol isn't food-grade corn. You wouldn't eat it. It doesn't look right. This is fuel corn, low-down, dirty product put into the process. Right there you're off-base and the other thing too is, yes, corn prices have gone up because more and more farmers are growing it and the demand is bigger and that's putting a stranglehold on other crops. Well, that's because for the first time in 75 years corn farmers are actually seeing the value in their marketplace going up.

"The housing markets have done that, other crops have done that, so for once the corn market has gone up and everyone is having a fit about it. It's not putting a stranglehold on food corn; we're actually at a surplus of that in the United States. Big Oil is in a lot of people's pockets and it's hard to trace that. There's a lot of propaganda.''

Part of the answer, possibly, is cellulosic ethanol. The substance yields more energy than needed to produce and can be made from almost any organic substance from beer waste to forest waste.

But clearly there are more areas to explore than just fuel.

The TDI Cup has partnered with Washington, D.C.-based Carbonfund.org to certify itself as the first "carbon neutral" race series. The new developmental series, begun as a platform to market Volkswagen's diesels' efficiency and sportiness -- with a side mission of identifying new drivers -- pre-funded reforestation programs which support the sequestering of carbon emissions to offset its pollution. Carbonfund.org, using a proprietary formula that accounts for competition- and fan-produced pollution, estimated the series will emit 263.25 metric tons of carbon during its entire season. The price to offset a metric ton of carbon, according to spokesman Russell Simon, is $5.50.

Carfax, the sponsor of a 2007 Nationwide Series race at Michigan International Speedway, became the first to offset a NASCAR race when it made a donation to negate its 4,394 metric tons of carbon output.

The Daytona 500, according to Carbonfund.org, emits an estimated 14,163 metric tons, which according to the Environmental Protection Agency is the same amount of Co2 produced from the burning of 5,894,552 gallons of gasoline and would require 1,331,564 seedlings growing for a decade to sequester.

A typical NFL game: 561.4 metric tons.

Howard Comstock and Doug Robinson foresee a day when such measures won't be necessary. But Comstock, Sprint Cup engineering program manager for Dodge, said NASCAR isn't moving fast enough on modernization. He said he'd like to race "on water" -- i.e. hydrogen cells.

For now, Comstock would at least like to see NASCAR embrace more technology, specifically fuel injectors, a fixture of passenger cars, instead of carburators. In spending hundreds of millions to improve 1955 engine technology, NASCAR is basically using a jet propulsion laboratory to make a better arrowhead.

"Fuel injection, even though you're using gasoline, unleaded fuel is certainly greener than leaded fuel and fuel-injected cars are better fuel economy, less polluting than carbureted cars and eventually I'm sure we'll go that way," Comstock said.

As North America's most popular and visible form of racing, NASCAR has great power in affecting change, has yet to unveil anything substantial from its R&D center that responds to France's call to action. It may need to relax its reticence to infuse in-car technology into its formula to do so.

Nelson, now a consultant who works with several teams and series, said NASCAR does not make change quickly.

"If there is any change directionally, it definitely will be something NASCAR has thought out and done a ton of behind-the-scenes homework on before its even public," he said.

An advocate and developer of NASCAR's so-called "Car of Tomorrow,'' Nelson culls ideas from various regimens. He pinched the idea of putting a rear wing on the COT by hanging out in IRL inspection lines and was again making mental notes at the season-opener in March at Homestead-Miami Speedway. He offered up that his next big project is likely green-oriented, and "coming along pretty well," but stopped short of saying for whom and when.

"If I told you that, you'd have your headline," he said.

Robinson, executive director of the International Motor Sports Association, which sanctions the ALMS, said manufacturers in his series are working on carbon-collection devices and that Peugeot would debut a hybrid engine by next season. Two more companies are developing hybrids, Robinson said, and another is working on a gas/electric motor. Yet another, he said, is exploring technology to replace batteries with supercapacitors and collect kinetic energy from braking to be stored and used for other functions.

"With the hybrid technology, which can still use renewable fuels for the fuel part, and they're even looking at collecting some thermal energy from the exhaust, and after treatments for the ignitions, trying to clean up what is emitted from the car," he said. "That's coming in a year or two."

The series has already taken the lead -- as far as current science is concerned -- by deriving the ethanol that comprises 85 percent of its race fuel from a cellulosic process utilizing Black Hills Forest waste. Some teams use diesel, but race cars do not get good gas mileage in any instance.

Devising a rulebook to take into account different fuels and sizes of fuel cells would be seemingly difficult, but Robinson said the series has already proved proficient while making competition fair with the various fuels in use. The key, he said, is "the BTUs and the caloric value of the fuel and the quantity you have onboard will allow you to race at a similar pace on the track and get the same number of laps before they have to visit to pits to refill."

"It's difficult and some days it's tough," he said.

And others are trying, too.

Formula 1, which is slated to use some renewable fuels beginning in 2009, imposed a 10-year ban on engine development last year and is exploring kinetic energy recovery systems, highly-efficient batteries and hybrid engine technologies. F1 teams spending in excess of $200 million a season on one program could provide the jumping-off point for quantum advancements that eventually impact passenger cars. The A1GP announced plans to possibly recycle race tires and has reduced its air travel by a third, because, according to CEO Pete da Silva, "We have a responsibility to conduct our business in a manner which minimizes the impact of our operations on the environment.''

Nelson disputes broad-brush claims that racing is in general more polluting than other major sports, but he knows there is a need for change. His affinity for technology just makes it more fascinating.

"Years ago we tried to get to 500 horsepower and we thought that would be it," he said. "Now that engine gets 800. You can never look down the road and say, 'That's as good as you're going to get.' ... If people are working on it, it will get better, and people are working on it."