Inside the SuperClubs: How Bayern Munich emerged as a world power

This story, which appeared in the Nov. 17, 2014, issue of Sports Illustrated, is the opening piece in a week-long series looking into the Superclub that is Bayern Munich. Subscribe to the magazine here.

You can’t conquer the world until you rule your own city. For Bayern Munich, one of the most remarkable success stories in global sports, its Bavarian Bildungsroman hinged on the playground decision of a 13-year-old.

Franz Beckenbauer, the greatest soccer player in German history, can’t help but laugh as he tells the story. In the fall of 1958, Beckenbauer and his friends played in a youth tournament against a team from his hometown powerhouse, 1860 Munich, which he’d been planning to join. The boy who would become the Kaiser, the world’s gold standard for defenders, was a forward in those days, small and sneaky, and his marker was an old-fashioned bully.

“He was maybe twice my size, and he hit me a few times; then he hit my face,” recalls Beckenbauer, now 69. “After the game, I said to my teammates, ‘I’m not going to 1860. I’m going to Bayern.’ And all my teammates, who also wanted to go to 1860, came with me to Bayern,” which at the time was the less popular club.

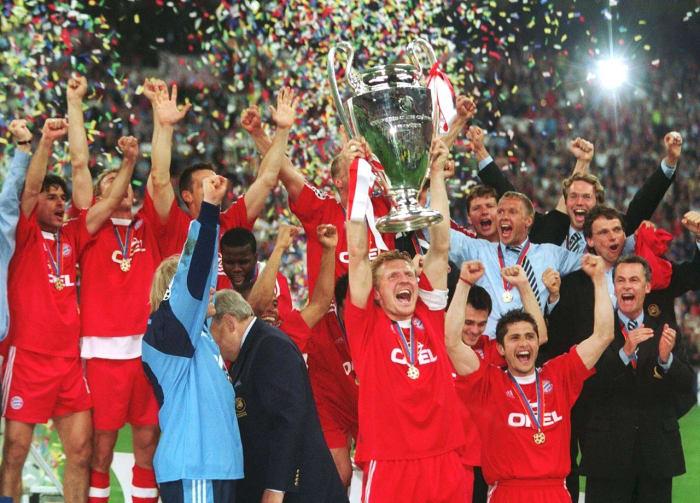

Behind Beckenbauer and, later, an assembly line of German sports idols, Bayern Munich has been winning trophies—and new fans—ever since. Promotion to the top-division Bundesliga came in 1965, followed by a first Bundesliga title in ’69 and three straight European Cup crowns from ’74 through ’76.

These days, while poor old rival 1860 snorkels in the second division, Bayern boasts arguably the world’s best manager, Pep Guardiola, and its top collection of players, including six newly minted World Cup champions. At a time when Middle Eastern sheiks and Russian oligarchs have turned European soccer into a Wild West of spending, Bayern is debt-free, owns its space-age stadium and preaches the social responsibility that comes with majority ownership by 235,000 dues-paying members.

• GALLERY: Spanning the globe for the world's best tifos

Mia san mia (We are who we are), Bayern Munich’s slogan proclaims, and while much has changed since Beckenbauer was 13, the club still takes pride in developing its own stars from an early age. Three of those World Cup winners joined Bayern’s academy as kids: forward Thomas Muller (at 10), defender Philipp Lahm (11) and midfielder Bastian Schweinsteiger (13). U.S. forward Julian Green, 19 and currently on loan to Hamburg, began training with Bayern when he was 12.

“Every day I feel this is my place,” Schweinsteiger says at Bayern’s headquarters on the leafy Säbener Strasse, in southern Munich. He grins. “I know all the people here. I even know where all the toilets are.”

Says Lahm, now the team's captain: “My first memories with Bayern are being one of the ball boys in the [old] Olympic Stadium, which is fantastic for an 11-year-old. Even the youth department was very professional.”

For Muller, playing at the team’s complex at age 10 was worth the difficult trek by train from his home 30 miles away. “It was amazing,” he says, “because I am a Bayern fan since I can think about football.”

Bayern embraces its Bavarian identity, never more so than during its annual Oktoberfest extravaganza, replete with lederhosen and giant mugs of lager. But the club faces outward, too.

“When the Berlin Wall came down, Bayern went to East Germany every summer for camp and friendlies, so they cultivated the entirety of Germany,” says U.S. coach Jurgen Klinsmann, who was first a player and then a manager for Bayern. “Now they are trying to do the same internationally.”

Last year Bayern’s newly hired director of global strategy, Jörg Wacker, came up with a plan. Realizing that the club was lagging behind Manchester United, Real Madrid and Barcelona in fandom, he focused Bayern on expanding its footprint in two countries, the U.S. and China. So in late July, just as the team was starting an exhibition tour in the U.S. (and riding World Cup–fueled soccer fever), Bayern did something that none of those other clubs has yet done: It opened a full-time office in New York City.

• MORE: Bayern's Neuer ruled out for Germany's friendly vs. Spain

Not long before that, Bayern welcomed 30 journalists from China’s CCTV network to Munich for a few days. At one point the delegation piled out of its bus carrying a boulder-sized soccer ball, which a group of Bayern youth players gamely tried to juggle for the journalists’ cameras.

Give the team some credit for trying, even though there’s no guarantee it can reach Wacker’s five-year goal: that almost every American be aware of Bayern Munich. Yet Karl-Heinz Rummenigge, the former Bayern forward and current club chairman, knows the most important way to win new fans is to keep winning games.

“We can offer something maybe others can’t,” he says. “We’ve won eight [trophies] in the last two years.”

But here’s the fascinating thing about Bayern Munich: For the ultimate perfectionist manager—and perhaps for his bosses, too—just winning may not be enough.

Pep Guardiola is trying to mold Bayern Munich into the perfect team, even with all of its past successes.

Alexander Hassenstein/FC Bayern/Getty Images

How do you make the world’s best team better? That was the meta-challenge facing Guardiola when he took over as Bayern’s manager in July 2013. Under the Spaniard’s predecessor, Jupp Heynckes, Bayern had swept to a continental treble in ’12–13, claiming the Champions League, Bundesliga and German Cup trophies in the same campaign for the first time in the team’s history.

Guardiola, 43, is one of the few managers in world soccer who can decide where he wants to go, having led Barcelona to 14 trophies in 19 competitions from ’08 to ’12, and he chose Bayern after a yearlong sabbatical.

How exacting is Guardiola? Maybe the most apt comparison is to Jiro Ono, the Japanese master chef who’s the subject of the documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi. In that movie, Ono makes his apprentice redo the same basic recipe for egg tamago hundreds of times before finally giving his approval. (That apprentice, Daisuke Nakazawa, is now one of the most revered sushi chefs in New York City.) So it goes with Guardiola, who has been known to dedicate large portions of practice to teaching world champions the basic technique of passing.

• WAHL: Bayern stars Schweinsteiger, Robben offer glowing endorsement of USA's Green

“Sometimes he stops training and just talks, talks, talks,” says Green. “Every sentence, you think, Yeah, that’s true. If he has an idea, he wants you to do it the way he thinks best. There’s no other thing that works.”

Nor does it matter how accomplished a player may be. Thierry Henry was 31 and one of his generation’s preeminent forwards when Guardiola became his coach in 2008 with Barcelona.

“Whatever you are thinking of when you play against his team, he already thought about it three days before you did,” Henry says. “He will be ahead of you on everything: on free kicks, on throw-ins. . . . And he demands a lot from his players. I remember games when we were leading 5–0 at halftime—and he wasn’t happy. He wants perfection in training, outside the field, in games. So you’d better be ready.”

To speak to Bayern players and administrators about Guardiola is to grasp that the team’s aspirations are higher than merely winning championships. There’s something noble about their pursuit, even if the goal may be unobtainable. “He wants us to play the perfect football,” says Schweinsteiger.

“I’ve got some experience, but I am still learning from him,” says winger Arjen Robben. “There’s always a possibility to make one step up.”

“Pep Guardiola is a coaching genius,” says sporting director Matthias Sammer. “And a fantastic worker,” adds Rummenigge.

• WAHL: Q&A with Bayern CEO Karl-Heinz Rummenigge

It was no accident that Guardiola chose Bayern for his next stop after playing and coaching at Barcelona. The two clubs share a philosophical kinship: Each is majority-owned by its members, preaches a social mission and is viewed as the People’s Club. Each relies heavily on developing players at its youth academy.

If anything, Bayern has more financial stability than Barça, not least because the German club has sold minority shares in the past decade to Adidas, Audi and Allianz. Now that Bayern is debt-free, the club has acquired land near its nine-year-old, 71,000-seat Allianz Arena to build a new youth academy, which will open by 2017.

But playing style is another matter, and by moving from the Spanish to the German soccer culture, Guardiola has embarked on a journey not unlike Picasso’s from the Blue Period to the Rose Period. At Barcelona, Guardiola presided over the apotheosis of tiki-taka, employing short passes to dominate possession, move slowly downfield and suffocate opponents. In the season before Guardiola’s arrival, Bayern had won everything with a more traditional German approach, relying on superior athleticism and blistering counterattacks after defending mostly in its own end of the field.

Guardiola, who learned to speak German before his move, argues that he now has to be the one to change, that he can’t simply graft tiki-taka onto Bayern’s DNA.

“I have to adapt to the players,” he says. “Of course I have an idea [of what I want to do], but when you talk about tactics, we have to talk about the skills of our players. You have to analyze your talent and make an agreement together. That is the best way for the team.”

Yes, Guardiola has made changes. He brought in Thiago Alcântara, a promising young midfielder, from Barcelona. And he stunned Bayern followers last year by moving Lahm, arguably the world’s best right back, to the central midfield. He called Lahm “the most intelligent player I have ever coached”—no small statement from someone who has managed Xavi, Lionel Messi and Andrés Iniesta—and the switch worked. Likewise, Guardiola asked goalkeeper Manuel Neuer to become more of a “sweeper keeper,” venturing far outside his goal to patrol the back and allow Bayern’s defensive line to play higher up the field.

“[Guardiola] changed the way we defend and attack a little bit,” says Müller. “With Heynckes . . . we played more directly to the goal, with more risk but a bit less control. Now we want to play the whole game in the half of the opponent, defend and attack there. Attack with control.”

That’s the buzzword: control. “The coach is pretty simple,” says Lahm. “He wants control over the game. Preferably for the full 90 minutes.”

Lifting trophies has become a regular occurrence for (from left) Bayern's Philipp Lahm, Arjen Robben, Bastian Schweinsteiger and Thomas Muller.

Adam Pretty/Bongarts/Getty Images

The result has been a fusion of styles that may well represent the Next Step in an ever-evolving sport, especially now that the tiki-taka era appears to be waning. “I think it’s a really good mix of the Barcelona style and the Bavarian style,” says Schweinsteiger. “In Germany you have the running and never giving up. For me, the first step is to have your own tradition, and then mix it a little bit with the Spanish or Barcelona soccer. We are Germany, you know?”

Don’t be fooled, though: Guardiola’s tenure has been a high-wire act, owing to outrageous expectations and—let’s be honest—differences in taste between Spain and Germany. In March, Bayern was dominating Champions League play and riding a 49-game Bundesliga unbeaten streak when Beckenbauer opened fire on the team’s playing style.

“In the end, we’ll be unwatchable like Barça,” he harrumphed. “They’ll be passing it backward on the goal line.”

Beckenbauer now says that he was simply reacting to a single moment: Guardiola had complained after Schweinsteiger took an errant shot from 25 yards out. “You have a lot of different facets in football—dribbling, crosses, whatever—but if you start to play with only one facet [short passes], it’s bad,” says the Kaiser. “Let’s have all the facets; that’s the most attractive football. It was only this situation. I was complaining about the style, but in general I am very happy with the way they play. They could be finishing more from the second line or from distance, but I am very pleased with their performance.”

One aspect of Bayern’s venerable tradition is the strong presence of former star players among the club’s directors, whether it’s Rummenigge, Beckenbauer (now in a ceremonial position) or Uli Hoeness, the former chairman who’s considered the father of the modern Bayern and remains beloved despite a recent 42-month jail sentence for tax evasion. And over the years, Bayern’s directors haven’t hesitated to make their strong opinions known to the club’s managers, publicly and in the boardroom.

• REMEMBER WHEN: Guardiola brushes off MLS All-Star game altercation with Porter

For Klinsmann, who was fired in 2009 after less than one season as Bayern’s coach, that structure has negatives as well as positives. “It’s tricky when opinions clash; how do you now find a common ground?” he asks. “I didn’t find that. I had a different opinion on how I wanted to develop a team and buy players. On the other hand, it’s very positive because you’re talking to soccer people. When you argue about a player, a system, a style, you’re arguing with people who know what they’re talking about—which is sometimes fun. Let’s have that deepened [conversation], let’s go at each other. I didn’t fit into this way, so it was good that we parted ways. But in a certain way it is unique.”

By any rational standard, Guardiola’s first season at Bayern was a raging success. His club won the Bundesliga by 19 points, clinching the title with more than six weeks to spare, earlier than any other team in league history. Bayern raised the German Cup again and made easy work of the FIFA Club World Cup. But in relative terms, the team’s performance dipped in the spring. The Bundesliga unbeaten streak ended at 53, and hopes for a Champions League repeat collapsed in the semifinals against Real Madrid.

“It was a very good season,” says Lahm, “but after we won the championship early in March, the pressure dropped. That led to a little dip in concentration. That’s normal after playing at an absolute top level for over one and a half years.”

Reasonable fans understood. Less reasonable ones noted that Guardiola had failed to make the world’s best team better—at least in terms of results. When Rummenigge announced before this season that Bayern would never fire Guardiola under any circumstances, he was trying to be supportive. But why did he feel the need to bring it up?

On a breezy Wednesday in Munich, on an other-wise quiet residential street, the red-wrapped fans gather five-deep around a practice field at Bayern’s modest headquarters. Just a few feet away, their soccer idols are training: Schweinsteiger and Lahm, Neuer and Müller, Robben and winger Franck Ribéry. Not every practice is open to the public, and Guardiola had the club install a giant curtain that can be pulled around the field when he wants things to be on the down-low. But during his 35 years as a team executive, Hoeness always insisted that Bayern remain open to fans as a public trust, no matter how many piled in.

“From the beginning, we told our fans, Come! Watch us practice,” says Beckenbauer. “But when I was a player for Bayern Munich in the ’60s there were maybe 10 or 20 fans watching practice. Now you have thousands.”

In most ways, modern European soccer is noted for its unfettered capitalism, for the absence of salary caps and for the runaway ticket prices that are the norm in the wildly successful English Premier League. But German clubs still keep costs low for at least some of the seats in their stadiums. At Bayern, season tickets can still be purchased for as little as $180.

• MORE: MLS owners growing more frustrated with Klinsmann

“If you’re a poor guy but you’re a Bayern Munich supporter, then our goal has always been to give you the possibility to go to the stadium to watch a Bayern Munich game,” says Rummenigge. “In the southern stands, for example, you pay around [$19]. We could charge three times that price, but we feel there is a kind of social responsibility.”

Now that Bayern has six current World Cup holders, plus another from 2010 (midfielder Xabi Alonso, purchased in August), and two more ’14 semifinalists (Robben and defender Dante), Rummenigge is probably underestimating how much those tickets could fetch without any price restraints. Such is the ruthless nature of European club soccer that it’s hard to enjoy raising a World Cup for very long before you’re faced with another searing challenge to your ability. Soccer never stops, not for anyone.

“The World Cup is the biggest title you can win, a fantastic feeling,” says Lahm, “but the drawback is the short vacation and preseason to prepare for a new season. You have to be motivated 100%, which isn’t so easy after such a great triumph.”

That may be true, but it’s also one more reason to watch Bayern Munich this season. How do the best respond to new tests? And how close can a team get to perfection? There’s always a possibility to make one step up.