Tactical breakdown: How Jurgen Klopp is transforming Liverpool

Jurgen Klopp’s one-liners remain famous years after he produces them. His proclamation of love for “heavy metal” football offers endless entertainment, and his touchline charisma can’t be taught in any coaching course.

He might lament his own sayings at times—“The problem with my life is that I've said too much s--- in the past, and no one forgets it,” he said in an early press conference at Liverpool—but they can also be taken as an axiom of his philosophy on the game.

In particular, Klopp rode his notion that “gegenpressing is the best playmaker there is” to great success at Borussia Dortmund. His new team doesn’t live and die through gegenpressing as much as regular pressing so far (more on the differences between the two later), but Liverpool has certainly become a highly structured side.

Its new calculated system of space control and ball pressure manipulates opponents into making poor decisions and giving up possession high up the field. The outcome, as it often was with Klopp’s teams in Dortmund, is an interception in a favorable area or a long ball that the defense can win without much trouble.

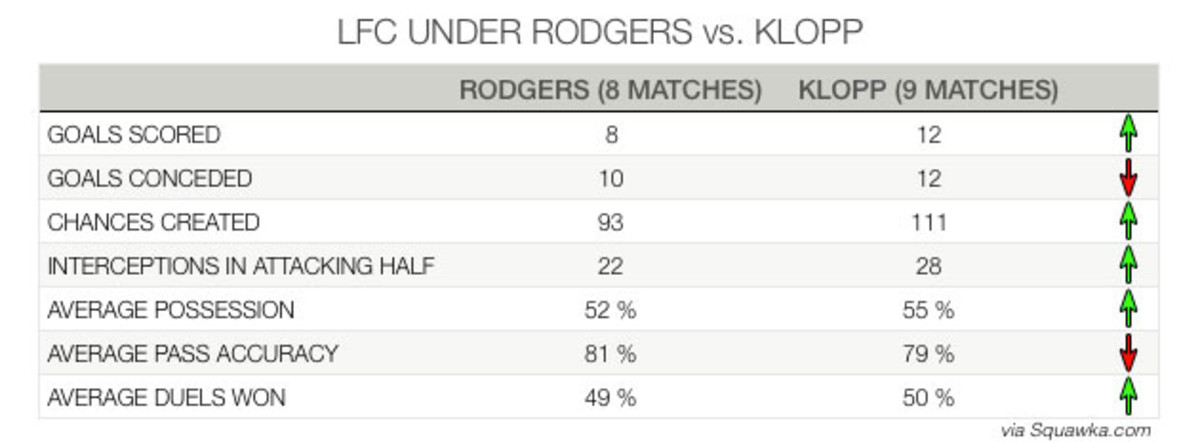

The results so far have been somewhat mixed, with an good early run of form followed by the current slump of four games without a win in all competitions. Still, the numbers point to a favorable general trend in Klopp’s league matches compared to Brendan Rodgers’ shortened season.

Tactical breakdown: How Ranieri's Leicester City has overtaken the EPL

Liverpool has averaged over a goal a game under Klopp, and though the Reds have also conceded at a slightly higher rate, that’s partly down to the natural adaptation period when a new manager arrives. The statistical differences point to the change in philosophy; Liverpool intercepts more balls in the attacking half now, wins more duels and maintains more possession despite a lower passing accuracy.

Klopp’s focus on the defensive is quite different than José Mourinho’s, with an emphasis on winning the ball back quickly and going straight to goal. The common idea is preying on opposition errors, but rather than patiently waiting for them to develop, Liverpool seeks to cause them by creating chaos and panic as the other team tries to build its attack.

After some tinkering with systems, debuting in a 4-3-2-1 and even trying a 4-4-2 with a diamond midfield in the 6-1 demolition of Southampton in the League Cup, Klopp has settled on the standard 4-2-3-1. His departures from a one-forward formation usually coincide with having more than one target-type strikers available, in which case two will play ahead of a withdrawn playmaker and narrow midfield.

What's next for Pep Guardiola after exit from Bayern Munich?

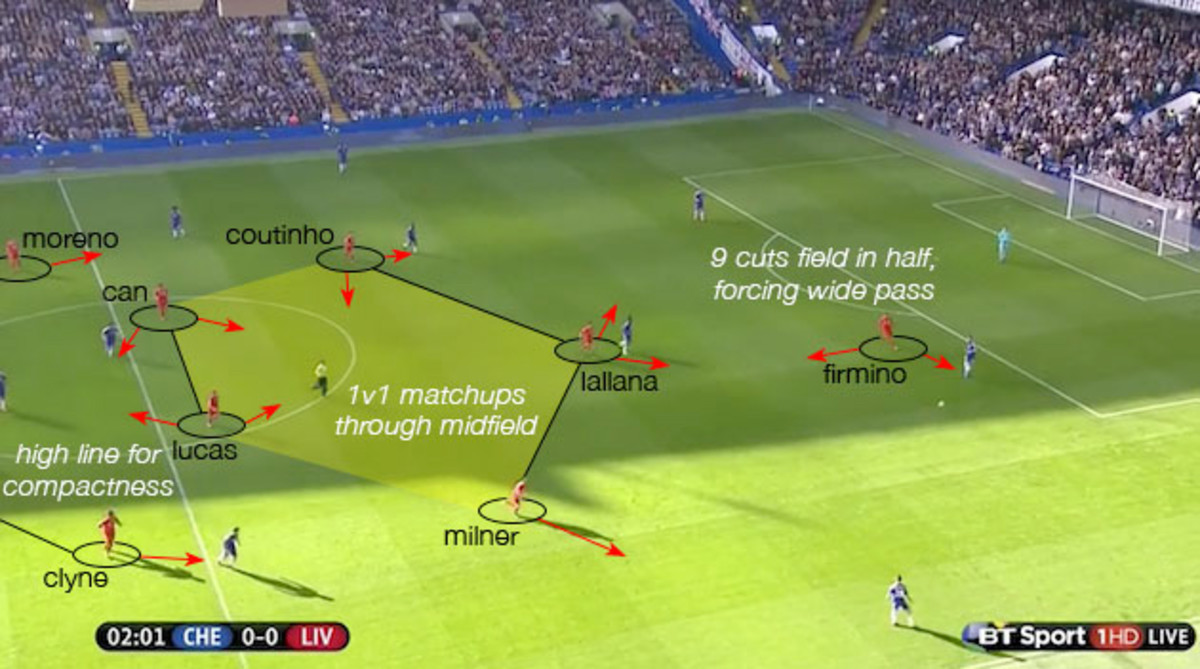

Regardless of the formation, the principles of play remain the same. When the opponent commits to playing on one half of the field, such as when a center back receives the ball, the highest man cuts the field in half with his run, forcing the next pass wide.

Meanwhile, the midfield is clogged with one-on-one matchups and a high back line to reduce the playable space as much as possible.

After enticing play to a fullback, the nearest midfielder steps out to press and the rest cut off central passing lanes, trapping the opposition (Coaches sometimes call this “using the touchline as a defender”).

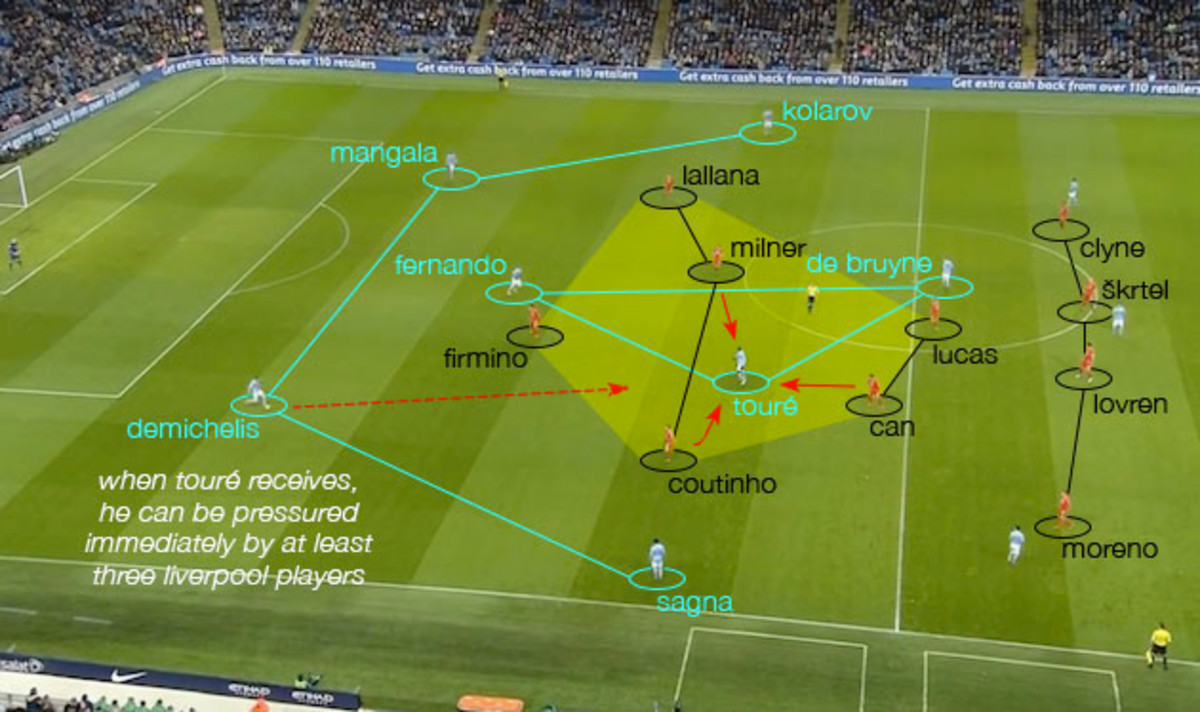

If the ball does go central, any receiving player can usually be closed down by at least three immediately. Playing the ball over the top will be met by central defenders comfortable in the air and fullbacks that can cover ground quickly with their speed, as well as a goalkeeper sweeping off his line.

It’s a disciplined defensive system that requires a great deal of focus from the players, but they also have the flexibility to counter however the opposition decides to attack. The key is, once opponents play the ball into midfield, Liverpool is in position to close down zonally with numbers around the ball.

That’s pressing: creating a situation designed to regain possession in a certain area of the field. Gegenpressing, or counter-pressing in English, is pressing specifically at the moment when a team transitions from attack to defense.

When a team loses possession, the normal response is to regain shape and balance so the opponent cannot easily break lines and move the ball toward goal. In that case, the transition moment is slower and leads to an organized, regrouped collective that can once again look to win the ball.

A counter-pressing team essentially eschews the organizational portion and immediately hunts the ball in a pack, compact and closely connected. In this sense, what should be a moment of disadvantage becomes the opposite, as the opponent is likeliest to be disorganized at the moment of losing possession.

At times, teams can even give the ball away intentionally simply to initiate their counter-press. This is where Klopp’s notion about gegenpressing as a playmaker comes in; if a team can organize itself for that transition moment while still in possession, as Liverpool does with its narrow midfield, the opposition won’t be able to gain any space when it wins the ball and will likely give it right back.

'Betrayed' Jose Mourinho reached untenable point at Chelsea

Klopp prefers a space-oriented counter-pressing system, in which a number of players converge on the ball and the space immediately surrounding it, cutting off all options by suffocating the player in possession. Other possibilities include a man-oriented press, in which defenders cover opponents one-on-one, and ball-oriented gegenpressing, in which multiple players aggressively pressure the ball.

(For more details on the tactical theory behind counter-pressing, read René Marić’s excellent analysis on Spielverlagerung).

However, even gegenpressing teams have a limit as to how long they press before regrouping. Pep Guardiola enacts a four-second rule with his teams, but the general guideline is if an opponent can successfully play out of a counter-press, the transition to defense cannot be overturned and so a team must reorganize.

The risk is a lack of collective understanding that creates a simple path to goal for the opposition, and that can only be neutralized with individual discipline and constant repetition in training. In theory, gegenpressing reduces that probability because a team would be pressing as far away from its own goal as possible if it loses the ball in the attacking third, leaving a lot of ground to be covered for an opponent to be dangerous.

The majority of Liverpool’s defensive actions have fallen into the category of simple pressing, which is to be expected as the team continues to adapt to Klopp’s philosophy. Individuals and teams learn concepts from simple to complex, so the micro-defensive tweaks that allow a team to gegenpress consistently can only be implemented after mastery of the manager’s macro-level changes.

In attack, players have the freedom to express themselves and let their natural tendencies take over. Roberto Firmino, Philippe Coutinho and Adam Lallana in particular combine and play off each other well. The five-man overload that lends itself so well to pressing and counter-pressing has a similar effect in attack because of the players’ technical abilities.

Immediate verticality leads to opportunities for them to combine quickly and creatively, much more so than long spells of sustained possession. James Milner’s flexibility creates versatility in all phases of the game, as he can play narrow or wider, higher or lower in midfield.

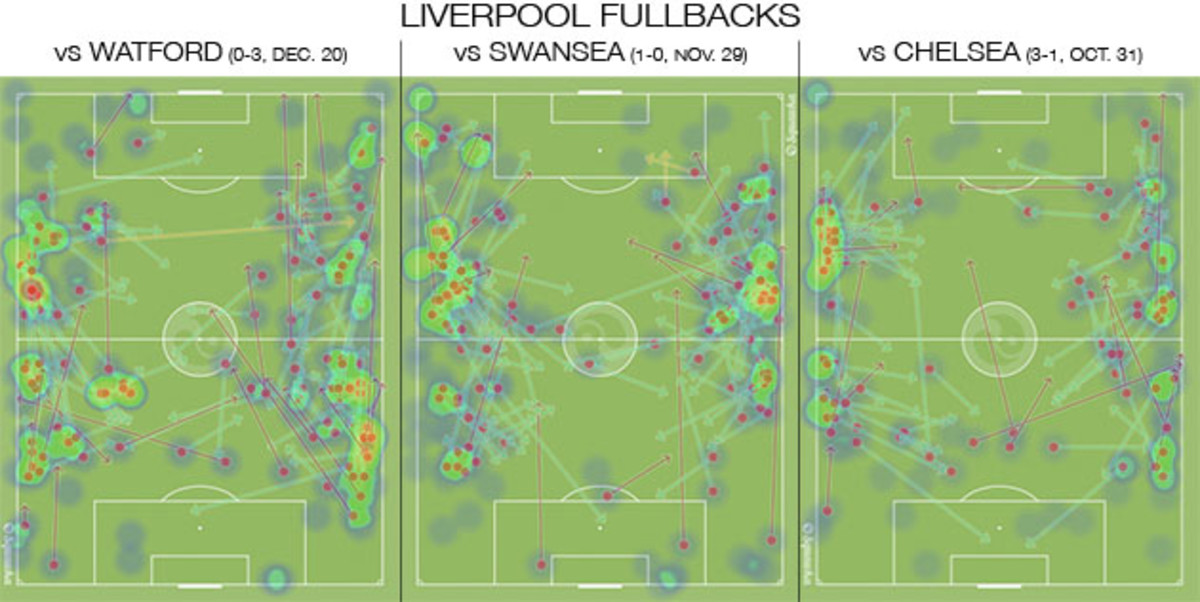

The one constant in Liverpool’s attack is the fullbacks providing width. The responsibility is heavier for Alberto Moreno on the left, where Coutinho generally stays pinched in, than Nathaniel Clyne on the right, who shares the work with Milner.

EPL Notes: Small clubs make big impact; off-field events add intrigue

Underneath the top line, Emre Can and Lucas Leiva play in a double-pivot arrangement (or doppelsechs, “double No. 6” in German).

Can usually pushes forward as more of a box-to-box midfielder, particularly in the left half-space, while Lucas supports the back line and occasionally flares out toward the right half-space in attack. Jordan Henderson can play in this space or one of the higher midfield spots.

Having strong forwards is a must in Klopp’s system, and Firmino, Daniel Sturridge, Christian Benteke and Divock Origi offer that option. They have shown that being an effective target man isn’t all about size, but rather having a creative dynamic with the No. 10 and other midfielders and an ability to hold the ball up or run into the wide channels when necessary.

Still, Liverpool’s attack seems to be built more on the players’ pre-dispositions than conscious choreography. At times, as Dortmund did in Klopp’s final season, the top six seem to lack ideas of how to move forward, especially against opponents who concede possession and sit in a lower defensive block.

Klopp’s challenges are similar to those he faced with BVB, but the Premier League’s open play and physical nature seem to lend themselves to his high-pressing ways. If he gets the time he needs and financial support in the transfer market, he could build a better version of what he had in Germany before too long at Anfield.