My Sportsman: Johann Olav Koss

Sports Illustrated will announce its choice for Sportsman of the Year on Dec. 6. Here's one of the nominations for that honor by an SI writer.

There is something inherent in the character of athletes, particularly those in individual sports, that lends itself to selfishness or, at the very least, intense self-involvement. "Your whole life revolves around your schedule, your body, your rehab, your workout," David Krummenacker, a world-class half-miler, told me once. "I hate to admit it, but it's true. And it sweeps in everyone around you."

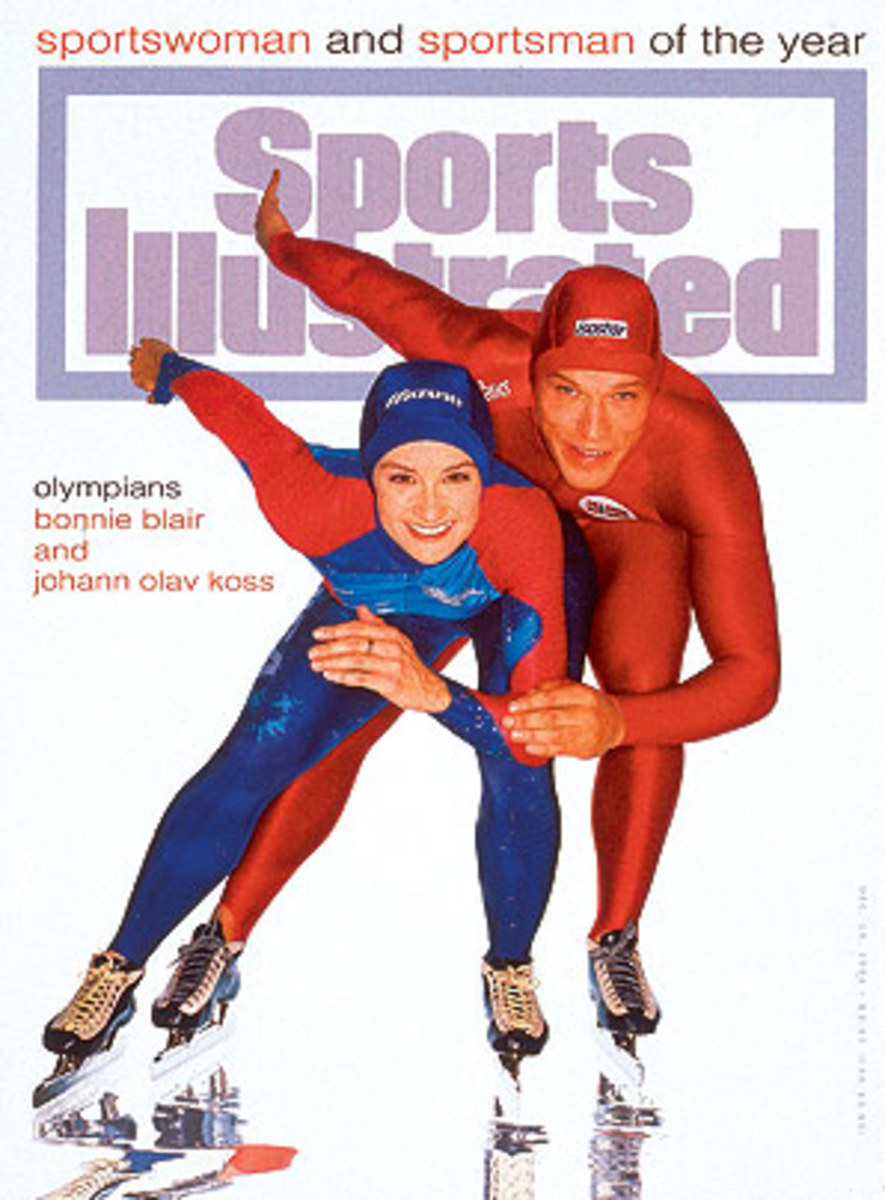

I have to assume that Johann Olav Koss had his selfish moments years ago, spending hour after solitary hour circumnavigating the skating oval in his native Norway, sharpening the skills and hardening the body that would win one gold medal in Albertville in 1992 and three more in his native land at the Lillehammer Games two years later. It was that performance, as well as Koss's modest demeanor and sense of sportsmanship that led Sports Illustrated to name him 1994's Co-Sportsman of the Year with U.S. skater Bonnie Blair.

But once his competitive days were through, the Norwegian legend did what only a few athletes (or non-athletes for that matter) do: Give time and energy to worthy pursuits that are never designed to grab headlines. Having already received SI's highest honor for what he did on the ice, Koss's nomination is a nod to two decades of notable achievement after he hung up his skates.

I met Koss at the 2000 Olympics, where I spent a day with him, or rather, trying to keep up with him. He scurried around Sydney, speechifying at various meetings (he was an IOC member) and handshaking at every stop. But he spent most of the time buttonholing potential donors and backers for Olympic Aid, an organization that established grassroots athletic programs for refugee children around the world. It was to that organization that Koss had donated his bonus money from the three golds he won in Lillehammer.

At the time, he had just returned from several trips to Eritrea, having introduced youngsters who had been displaced by border wars with Ethiopia to the joys of sport. His initial efforts gained him not praise from the Norwegian press, but rather skepticism that he was wasting time and money in war-torn countries. In true form, Koss simply deflected the criticism, much as he turned back most of the competition in his gilded competitive career.

He now runs Right to Play, a Toronto-based organization that evolved from Olympic Aid, and still does the grinding foundational work that rarely gets noticed. He has been to trouble spots such as Liberia, Uganda, Rwanda and Sudan, covering a road map of the Most Dangerous Places on Earth, demonstrating to young people victimized by violence the joy of sports and showing adults the simple truth that play can be an antidote to war. When SI colleague Alex Wolff talked to Koss recently, the Norwegian had just gotten back from the refugee camps at Sierra Leone. "The boys had a physical outlet for their aggression," Koss told Wolff. "The girls developed respect for their bodies."

Nominate a place where you wouldn't spend your vacation, and chances are Koss has been there.

Agenda Item 1 on the Get Noticed Plan of many athletes is "to do something for the kids." That often means a one-day event with a brief appearance, a few hugs and much attendant publicity. But Koss roams where newspapers tend not to print. It is his steadfastness, his resolute optimism and his results -- an estimated 700,000 kids in 20 countries are serviced by Right to Play each week -- that should earn Koss the distinction of being the first Sportsman of the Year both on and off the field.