Special night for Agassi, fans in Manhattan

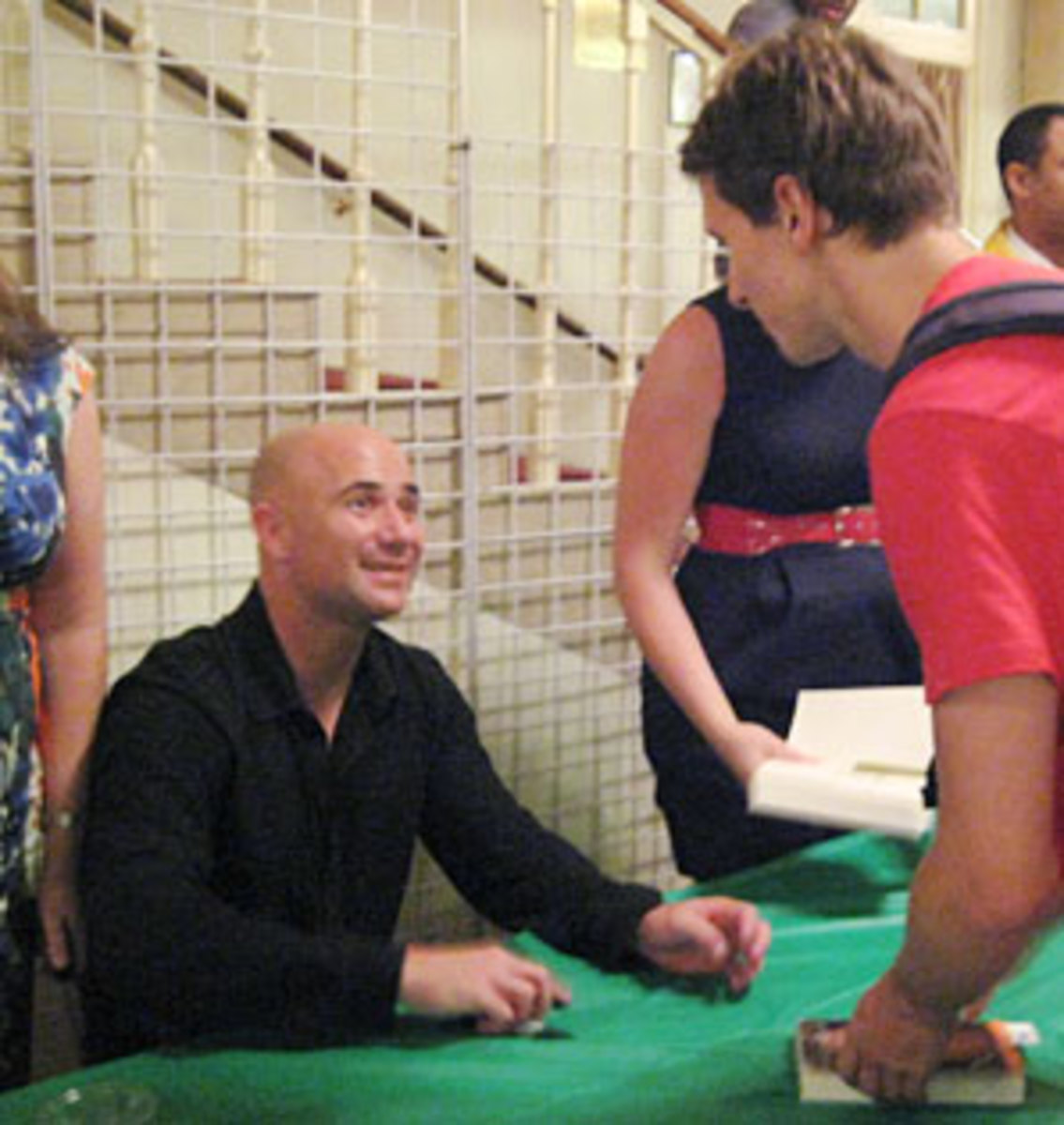

Andre Agassi signed books for attendees following Thursday's event. A $250 ticket included a private meet-and-greet afterward. (Alexandra Fenwick/SI)

It’s been four years since his last match at Flushing Meadows, but Andre Agassi can still hold court in New York in September. On Thursday night at Town Hall in midtown Manhattan, he sat down with ESPN commentator Rick Reilly for an Inside the Actors Studio-type interview, sponsored by the Tennis Channel, to cover the highs and lows of his life and career.

“I don’t want to unsettle you, but I’m actually freeballing tonight,” Agassi opened, a rejoinder to the revelations of going commando in his let-it-all-hang-out memoir, Open, published last year. Thus began "A Special Evening with Andre Agassi," an event billed by the promoters as "combination of interview, real-time talk show, tribute and roast."

That was the most startling new information given out during the two-hour session. Anyone who’s read Open -- presumably the majority of 800 in attendance -- should have already been familiar with the stories told onstage. Although Reilly kept the atmosphere light, at its heart the tale of Andre Agassi is a melancholy one, not so much the legend of a reluctant hero as it is the account of a young man from whom greatness was ruthlessly wrested like blood from a stone. There really isn’t anything funny about anecdotes like the one where Agassi’s father, Mike, in a fit of road rage, pointed a gun across the passenger’s seat at a neighboring car, the barrel just inches from a young Andre’s face. Or the one where Mike smashed a sportsmanship trophy in the parking lot shortly after it was awarded to Andre in a youth tournament.

Mike has not read Open and, according to Andre, never will. “I’m 80, I don’t care what anyone says about me,” the elder Agassi told his son. “If I could do it all over again, I’d do everything the same … except make you play tennis.

“I’d pick golf or baseball. Because you can play longer and make more money.”

Agassi’s true confessions about his mixed emotions (well, mostly hatred) for his sport haven’t dimmed his fans’ love for him. Mo Salth was jogging near the tennis center in Central Park a few weeks ago when he saw a poster advertising the Agassi event. He snapped up a pair of tickets to surprise his wife, Hilary Hotchkiss, a rabid tennis fan who has followed the Punisher’s exploits on and off the court since she was a teenager.

“We’re thinking of naming our child after Andre,” joked Hotchkiss, who is 35 weeks pregnant. The couple was among many who paid $250 a head to attend a private late-night reception with their idol after the interview at the nearby Grand Hyatt. (Tickets for the "once-in-a-lifetime event" started at $95.)

Also at the reception was a mother with her three young children, lucky enough to stay up past their bedtime to meet one of their favorite players. The family had traveled from Santa Monica, Calif., although the distinction of longest distance traversed surely belonged to Niki Iliev, who had made the 4,700-mile journey from Bulgaria.

Iliev had mistakenly purchased tickets to Thursday’s night session at the Open, assuming the Agassi event would be held in Queens. When he reached the National Tennis Center and realized his error, he promptly turned around and headed back into the city. “For me, Andre is number one,” he explained. “The rest of the U.S. Open is number two.”

Not that tennis is anything but a top priority. Iliev runs an amateur sport club called O.K. Sport that is trying to promote the sport in his home country. He said that Agassi is huge in Bulgaria, and waited in line at the reception’s meet-and-greet in hopes of inviting the man to come and see for himself. Agassi wouldn’t be the first -- Boris Becker visited Bulgaria last weekend for an exhibition match. “Three thousand people came to see Becker,” Iliev said. “If Agassi comes to Bulgaria, 10,000 will come.”

A surprising number of fans in attendance were teachers and counselors, an indication that people have embraced Agassi’s current incarnation as education advocate (his foundation operates Agassi Prep, a K-12 charter school in Las Vegas). It’s a role he’s clearly passionate about, although the ninth-grade dropout hastened to clarify, “Don’t confuse me for being an educator. I’ve always wanted to provide education, but I never thought I could be an educator. I always felt a lack of education in my own life.”

Despite that disclaimer, Agassi’s thoughtful interview last night revealed either that the eloquence of Open ghostwriter J.R. Moehringer has rubbed off on him, or that wisdom isn’t only gleaned from textbooks (probably a bit of both). It’s an understatement to say that the Andre of today is a much better-adjusted individual, able to relate dark memories without sounding like a downer, after having wrestled or at least processed most of his demons while working on his autobiography, a process he called a three-year therapy session.

You could even say that image is everything, after all: Agassi’s untamed (fake) mullet of the past betraying an unsettled personality hiding secrets and shame; the present’s smooth hairless pate reflecting an attitude of candor and zen.

* * * * *

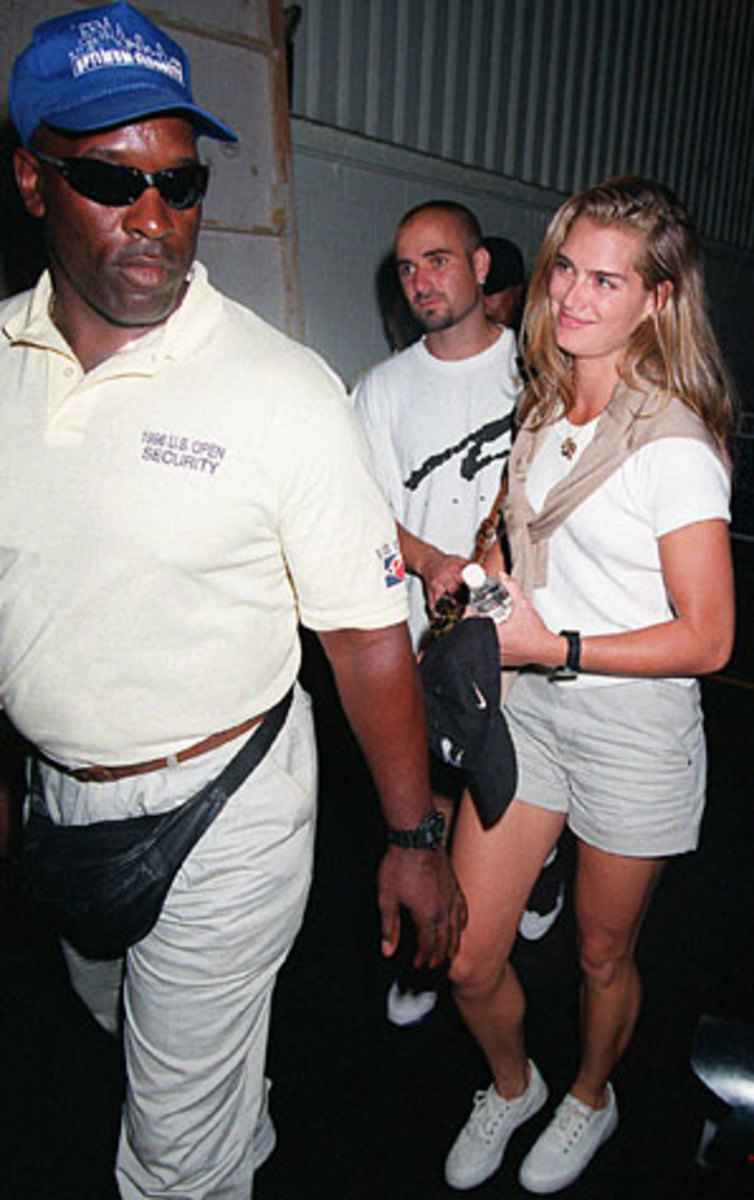

If you watched tennis during Andre Agassi's career, chances are you've seen James Rickenbacker (left) around. (Malcolm Clarke/AFP/Getty Images)

In the audience to hear Andre Agassi interviewed by Rick Reilly at Town Hall last night were a variety of characters, all there for their own reasons. There were the star-struck tennis-heads, there for a once-in-a-lifetime meeting with one of the sport's living legends. There were admiring guidance counselors and teachers, interested in Agassi’s charter school philanthropy. There were salivating tennis industry executives, interested in Agassi’s marketing potential.

And then, seated next to me in the front-and-center orchestra section, there was James Rickenbacker, a massive linebacker-sized man, wearing a Tony Soprano-styled button-down bowling shirt in cream and black, uncomfortably squeezed into the red velvet theater chair, his beefy forearms taking up both armrests.

Rickenbacker, 57, who worked as a security guard at the U.S. Open for over a dozen years, wasn’t looking to get an autograph or promote his after school program or cut a deal. He was simply there to see his old friend.

For two weeks every September, since 1995, it was Rickenbacker’s job to escort players from the tunnel to the court and back again and protect them during match play. From that vantage point, Rickenbacker was witness to a generation of tennis greats’ moments of glorious triumph and crushing defeat. He retired from the U.S. Open security detail last year but continues to work as a personal bodyguard to his longtime employer -- Donald Trump.

Agassi wrote in his autobiography, Open, which provided much of the fodder for the evening’s discussion, that James was always a familiar and comforting presence at the Open. Rickenbacker was there when Agassi retired from pro tennis in 2006.

“There are people you count on seeing at the U.S. Open -- office staffers, ball boys, trainers -- and their presence is always reassuring. They help you remember where and who you are. James is at the top of that list. He’s one of the first people I look for when I walk into Arthur Ashe Stadium. Seeing him, I know I’m back in New York, and I’m in good hands.”

And he was there again last night, cutting to the front of the book-signing line to give Agassi a grizzly-bear sized hug. As the two men clapped each other on the back, grinning, their matching bald heads glinted in the light.

Dishing about the backstage foibles of the world’s tennis greats, Rickenbacker told Reilly recently that he tried to avoid playing favorites -- but couldn’t resist when it came to Agassi.

"He was the kindest man, nicest player I ever worked for. He was real. Genuine. Not the least bit stuck on himself. Same for his wife [women's tennis player Steffi Graf]. Every time I'd see her, she'd come up and give me a big kiss. So many tennis players are spoiled. But not them. They're the best people."

And Agassi appreciated James’s camaraderie in a lonely sport that often drives players to talk to themselves as they pace the baseline. Before heading out to the court, Rickenbacker said he would exchange a single fist-bump with Agassi.

“(James’s) inability to remain impartial is endlessly charming,” Agassi wrote in his book. “During a grueling match, I’ll often catch James looking concerned, and I’ll whisper, ‘Don’t worry, James, I’ve got this chump today.’ It always makes him chuckle.”

Before landing the U.S. Open gig, Rickenbacker wasn’t much of a tennis fan, he said, but years of better-than-front-row seats to the then-green and now-blue courts of Arthur Ashe converted him. He misses working at the Open, he said, but at Agassi’s talk last night, he once again had the best seat in the house, even if it was a little small.

--Alexandra Fenwick