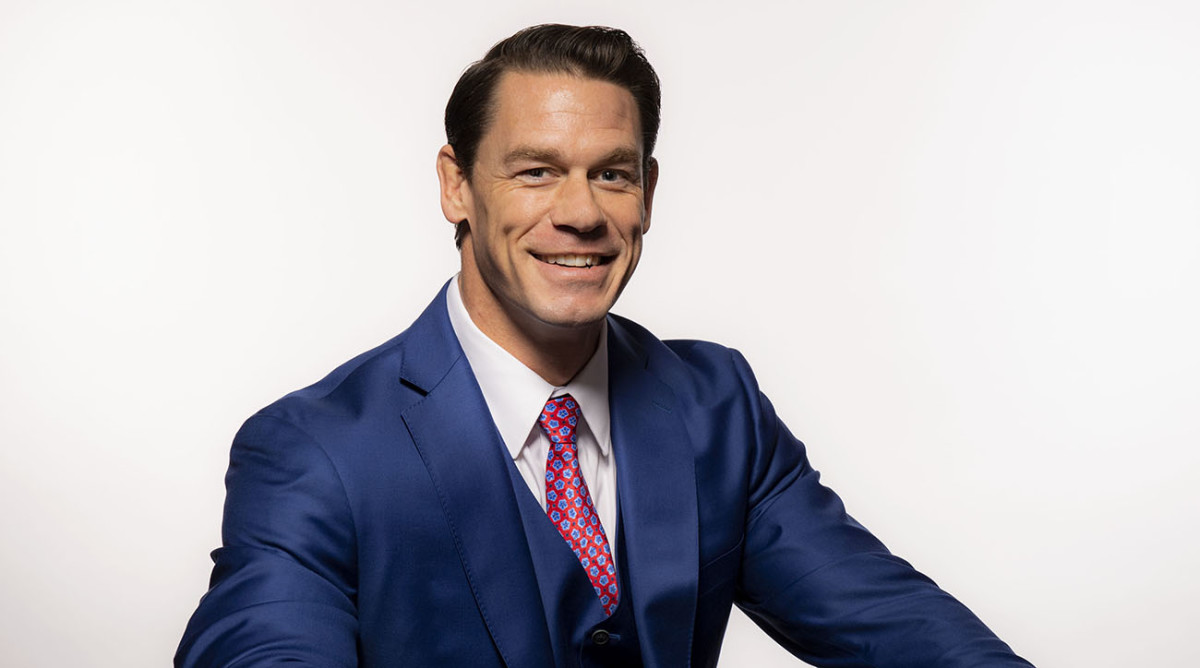

John Cena's Impact Is Felt Most Outside of the Ring

This story appears in the Dec. 17-24, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

John Cena is a good guy. You might have gathered that from watching him in WWE, where his charismatic do-gooder shtick has carried him to a generational level of stardom. Or maybe you got the gist from seeing him yuk it up with Ellen or Fallon or Colbert, a genial G.I. Joe action figure with GQ looks promoting his latest major Hollywood film. Yet what makes John Cena more than a pro wrestling hero or an amiable celebrity—what defines his actual character—is what he does when the only cameras on him are the smartphones of emotional parents watching their sick children fulfill a dream.

It's this John Cena who is the 2018 recipient of the Sports Illustrated Muhammad Ali Legacy Award. Over the last 16 years, as Cena's star has risen through 16 world championships in wrestling and several box-office hits, and as he has lent his fame to antibullying and cancer-awareness campaigns and spent his time visiting active and wounded troops, Cena, 41, has also become the most prolific celebrity in Make-A-Wish Foundation history. He has granted 580 wishes, meeting children battling all kinds of afflictions, including cancer and debilitating neurological disorders. That figure doesn't even include the dozens of "Wish Kids" at luncheons he hosts over WrestleMania weekend each spring, or the ones he seeks out backstage when they're meeting other WWE stars.

How Cena came to this role is part personal conviction, part pro wrestling's unusual nature. WWE has long branded itself as "sports entertainment," a label that rankles industry traditionalists but captures its essence: a hybrid of athletics and theatrics, as if it were a live-action comic book. In this way wrestling can be a perfect source from which children can draw heroes, offering idols more tangible than any Marvel blockbuster and even larger than life than any baseball or football player. Its performers occupy a unique space in many fans' minds as semi-fictional, semi-real-life characters—a blending made even more believable when, like Cena, they perform under their real names. "It's very much John Cena the character hoping, over the course of 30 minutes to an hour, to let them know John Cena the person," he says of time with kids, "and to know they're not too far apart—that me and the guy in the ball cap are the same."

Both Cena's on-screen character and off-screen impact derive from this dynamic. He broke into the industry quickly after moving from his native Massachusetts to California to pursue a career in bodybuilding upon graduating from Springfield College, where he was an All-America offensive lineman. He was working at a Gold's Gym and as a limo driver when he took up wrestling on a friend's suggestion and became hooked. After performing for smaller promotions, he made his official WWE debut at age 25 and found success in the early 2000s in the persona of a wisecracking, villainous rapper who dressed down opponents with sophomoric punch lines. Like many a witty heel before him, Cena wound up so beloved by the audience that WWE repositioned his character to leave the dark side but maintain the same brash ways. Shortly thereafter, in 2004, he was pulled into a backstage room before a show and asked to spend time with a family. Only later was he told they had been brought to the show by Make-A-Wish. To which Cena asked, "What's that?"

After reaching WWE's zenith as its champion in 2005, Cena noticed the faces chanting his name each night were becoming younger and more impressionable. He decided his character would shift in kind, either cleaning up his rhymes or ditching them entirely. Now that he had fans' attention, he thought he should try to tell them something.

Many colleagues thought it a career-threatening risk. But Cena hoped whoever believed in him would adopt his beliefs. He evolved slowly, first borrowing from common hip-hop language to adopt the mantra "Hustle. Loyalty. Respect." As that morphed into "Never Give Up," his words resonated better than anyone could have hoped. The message proved especially alluring for kids facing hardship. Latching on to his maxim, more children eligible for Make-A-Wish—those with critical or life-threatening medical conditions—began requesting to meet Cena than any other celebrity. He was happy to oblige. And oblige. And oblige.

At first Cena had hoped to keep his lofty Make-A-Wish stats quiet, lest people think he was just doing it for good p.r. When those at the foundation explained that touting them could help drive donations and fund more wishes, he became the charity's public face, appearing in campaigns ranging from video ads to special 7-Eleven coffee cups he helped design. He has even integrated his Make-A-Wish work into his WWE performances, at times wearing gifts from kids to the ring or giving kids a shout out on the microphone. In 2017, he celebrated his latest WWE championship by jumping the barricade at the Royal Rumble and draping his title belt over a Make-A-Wish participant's shoulder.

WWE's faux-competitive matches even allow him to heed kids' requests to weave certain moves into the show. "It's the ability of Babe Ruth to call his shot, all the time," Cena says. When things don't go as the kids had hoped, that too offers an opportunity. "I go and see them after I lose," says Cena, "and that's a great message to send: Hey, don't worry, I promise you—I promise you—I will get up and be able to keep going. I've seen kids break down and cry, and then in a split second turn their emotions to say, 'Right on, I believe you.'"

Before shows, Cena's conversations with kids range widely. Some fans recite facts from Cena's career that even he didn't know. Others want to play video games or talk about a shared love of vintage cars. "He really seems to be able to get to the heart of why each kid wants to meet him," says Make-A-Wish spokesman Jamie Sandys. In 2013, when Cena met a Pennsylvania native named Chloe who was battling neurofibromatosis, he received word that the starstruck seven-year-old had brought a toy tea set she'd received for Christmas. Cena asked if she wanted to have a tea party. "Her eyes lit up like the galaxy," says Chloe's father, Jose Concepcion. When Cena lifted his tiny cup by its handle, Chloe chided him for neglecting to raise his pinkie. Cena, clad in knee pads and full wrestling regalia, complied. "How cool is that, a big wrestler, manly-man type.... I thought that was the sweetest thing," says Jose, whose daughter is now almost 13. "They were talking like they had been friends forever. I know that's something Chloe will remember for the rest of her life."

Families write to Cena long after their meetings, sharing stories of how their child's well-being surged or, more somberly, how their child did not make it but found a moment of joy amid overwhelming struggle. The effect has been enduring on the man behind the branding too. "It will not allow me to have [a negative] perspective on life," Cena says. "We all have bad days, but when I find myself taking a turn down that road, I literally just stop and ask myself, 'O.K., what's so bad?'"

His character and status have allowed him to help with other causes too. In 2016 he received a USO award for his work with veterans; in recent years he has confided in young fans that even he was bullied growing up, and that he deals with harassment online to this day but refrains from responding negatively. This fall, when WWE went through with a widely criticized show in Saudi Arabia following the murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Turkey, Cena was one of two top stars (along with Daniel Bryan) to pull out of the event.

Shortly after the youngest of his four brothers, Sean, was diagnosed with Stage 4 brain cancer in 2011, Cena looked at the pink uniforms and equipment other sports use to raise breast-cancer awareness and asked why WWE wasn't doing the same. The following October, WWE's rings featured a pink middle rope and the company was selling pink permutations of dozens of wrestlers' merchandise, with profits going to the Susan G. Komen breast cancer foundation.

Other times the causes come to him. In 2016 the Ad Council recruited Cena to star in its "We Are America" video spot, in which he walks the streets of New Orleans delivering a three-minute monologue equating patriotism with a celebration of diversity. "As soon as I heard about it, I said yes," Cena says. "There were people saying, are you sure? I said, Yeah, I'm absolutely sure, because this is something that I believe in.... Every once in a while we need to be reminded everyone is welcome here."

Some WWE fans have long grown tired of Cena's upbeat act, booing him in the hopes that his character might be refreshed with a dose of malevolence. Now in what he calls "the definite twilight" of his in-ring career, Cena says that he will do whatever is required to establish his successor as WWE's next big star. "It's a giant relay race, and I'm in the phase where I'm handing the stick off," he says. "My time is up," he adds, riffing on the lyrics to his WWE entrance theme. "Someone else's time is now."

Yet whenever he throws his last suplex, he has no plans on leaving the philanthropic ring. "I'm not even close to done," says Cena. It's easy to believe.