The Hall of Fame cases for Cox, La Russa, Martin, Miller, Steinbrenner and Torre

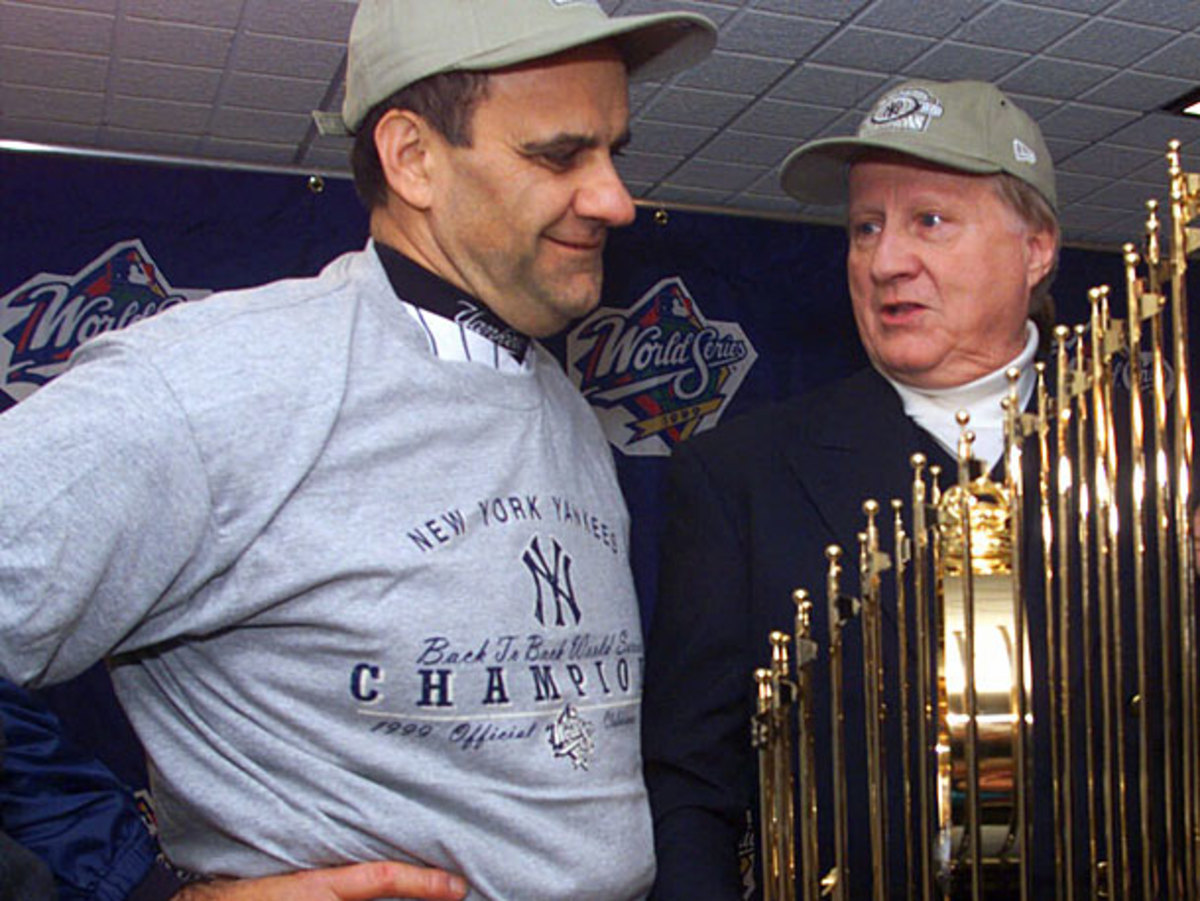

Joe Torre (left) and George Steinbrenner won four World Series together in New York but only one of them is a lock for Cooperstown. (AP)

The National Baseball Hall of Fame announced this year's Veterans Committee ballot on Monday. Covering the "expansion era," it lists 12 men -- six players, four managers, one owner and one union chief. Included in that group are three of the most accomplished managers of the last two decades. Jay Jaffe will take a look at the six players vis-a-vis his JAWS system. Meanwhile, here's a look at the other six, all of whom have strong arguments for induction and are listed in alphabetical order:

Bobby Cox, Manager

Atlanta Braves: 1978-81, 1990-2010; Toronto Blue Jays: 1982-85

The case for Cox's induction into the Hall of Fame is simple: From 1991 to 2005, his Braves made the postseason every year that there was one (the strike-shortened 1994 being the exception). That's 14 straight playoff berths, each one the result of a division title. No other team in the history of the game has had such a sustained run of success, not even the Yankees of recent vintage, who had their streak of consecutive postseasons snapped at 13 in 2008, and who were limited to the wild card in three of those years.

What's more, Atlanta had the worst record in baseball in 1990. Cox took over as manager in the middle of that season, then took the Braves to the World Series each of the next two years. In addition, the '91 team that went worst-to-first was one that he helped build as the club's general manager from October 1985 to October 1990, a period during which Atlanta drafted Chipper Jones, Steve Avery, Ryan Klesko, Mike Stanton, Mark Wohlers and Kent Mercker, and traded for John Smoltz and Charlie Leibrandt. Oh, and the year before he was hired by the Braves, he managed the Blue Jays to their first division title and postseason appearance.

The only knock against Cox's Braves is that they often fell short in the postseason, but they still won five pennants in a span of eight years (again, not counting 1994) and the championship in 1995. Cox's 2,504 wins rank fourth all-time in baseball history, and among managers with 2,000 or more wins, only Joe McCarthy, John McGraw, and Walter Alston, all Hall of Famers, finished with a higher winning percentage than his .556. He's a slam-dunk.

Tony La Russa, manager

Chicago White Sox: 1979-86; Oakland A's: 1986-1995; St. Louis Cardinals: 1996-2011

The three managers who won more games than Cox are Connie Mack, John McGraw and La Russa, who won 2,728, just 35 shy of the great McGraw. From 1979 to 2011, not a season passed without La Russa at the helm of a major league team, and he took all three of his organizations to the postseason. In 1983, he guided the White Sox to the playoffs for the first time since 1959. With the A's, he won three straight pennants from 1988 to 1990, something only Joe Torre's Yankees have done since, and he had his greatest success with the Cardinals. In La Russa's 16 years in St. Louis, the Redbirds went to the postseason nine times, winning three pennants and two World Series titles.

Along the way, La Russa revolutionized the way teams manage their bullpens. He redefined the role of bullpen aces and helped Dennis Eckersley become a first-ballot Hall of Famer by making him the first great one-inning closer, and his increased emphasis on platoon matchups led to the expanded and specialized bullpens of today's game. One can argue, quite convincingly, that those changes did not improve baseball, but the impact of those changes and La Russa's influence upon them is undeniable.

La Russa is another slam-dunk, though it's worth noting that he carries a significant stain from the Steroid Era as the manager of the late '80s A's teams that helped define those times. Also, as Mark McGwire's manager in both Oakland and St. Louis, he was at best a passive enabler as McGwire rewrote the game's record books with the help of steroids in the late '90s, which had a similarly influential impact on the use of performance-enhancing drugs around the game. If La Russa is held to the same standard that former players and Hall candidates like Jeff Bagwell and Mike Piazza have been, both of whom were effectively declared guilty by suspicion, he would not be inducted this year.

That said, this ballot is not voted on by the Baseball Writers' Association of America, but by a 16-member panel* comprised primarily of Hall of Fame players and managers (see the full panel below). I expect that group, 12 of whom (75 percent) need to vote for a candidate for that person to be inducted, will put La Russa in without much fuss.

Billy Martin, manager

Minnesota Twins: 1969; Detroit Tigers: 1971-73; Texas Rangers: 1973-75; New York Yankees: 1975-78, '79, '83, '85, '88; Oakland A's: 1980-82

On a ballot with Cox, La Russa and Torre, Martin is unlikely to get the support he needs for induction, though I for one believe he deserves a spot in Cooperstown. Martin doesn't have the raw wins totals of the other three because he was a volatile, self-destructive man who never held a managing job for more than four consecutive years without being fired or resigning, but his impact on the teams he managed was clear.

As a rookie manager with the Twins in 1969, he led Minnesota to an 18-game improvement and the AL West crown. In his first year with the Tigers in 1971, he guided Detroit to a 12-game improvement; in his second season the Tigers won the AL East. Fired by Detroit late in the 1973 season, he was hired by the Rangers before the year was over and, in '74, Texas made a 27-game improvement. The Rangers fired him in the middle of the 1975 season, but he was hired by the Yankees before that season was over and in '76 he helped them to a 14-game improvement and their first pennant in a dozen years. New York then won the World Series in 1977, Martin's only championship as a manager (matching Cox's total).

After resigning midway through the '78 season and then being rehired mid-way through the following season only to be fired after a now-infamous bar fight with a marshmallow salesman, he moved on to Oakland. In his first year with the A's, in 1980, he led them to a 29-game improvement and took them to the postseason in the strike-shortened 1981 season. He returned to the Yankees in 1983 and oversaw a 12-game improvement, and in 1985 shepherded New York to a 10-game improvement and the franchise's best showing during their playoff drought of 1982 to 1993, falling just two games shy of Cox's division-winning Blue Jays in the AL East. Martin got a fifth and final chance as Yankees manager in 1988 but didn't even make it out of June before being fired.

Quickly wearing out his welcome was a theme throughout Martin's career. His public behavior was often an embarrassment, as were his spats with and perpetual cycle of hiring and firing at the hands of George Steinbrenner. He could be a brilliant tactician, but he is also criticized with ruining the arms of his young Oakland staff in 1980. Despite all of that, I think his record is that of a Hall of Fame manager.

Marvin Miller, executive

Executive director of Major League Baseball Players Association: 1966-1982

Miller's continued absence from the Hall of Fame would be comical if it weren't, given his death last November, also tragic. He is long overdue for induction to Cooperstown. It can rather easily be argued that, since Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947, no single man has had a greater impact on the game than Miller. He took over a weak players union in 1966 and turned it into one of the most powerful in the country, legitimately unifying the players in a way they weren't before and winning countless gains in his 16 years as executive director.

The most significant and most celebrated of those gains was the redefinition of the reserve clause and the institution of free agency in 1975, but that wouldn't have been possible had Miller not won the players the right to have their grievances heard by an impartial arbitrator in 1970. Miller also instituted collective bargaining in 1968, won increases in the minimum salary and pension payments and the institution of the salary arbitration process in 1972. In sum, he almost completely tilted the balance of power in the sport from the owners to the union.

It's no surprise, then, that he has proven to be a controversial candidate for the Hall of Fame among voting committees populated by former executives and veteran reporters, many of whom resent the changes Miller brought to the game. Among the general population of players, fans and journalists, however, a baseball Hall of Fame without Marvin Miller is incomplete. There's hope that his omission from the Hall will finally be corrected this year.

George Steinbrenner, executive

Principal owner, New York Yankees: 1973-2010

As the principal owner of the game's signature franchise and a man possessed of an outsized and confrontational personality, George Steinbrenner was a huge presence in the game over the final quarter of the 20th century. From the time Steinbrenner's investment group bought the Yankees until his death in July 2010, New York won 11 pennants and seven World Series and went to the playoffs 19 times in 36 seasons. More memorably, he was the first owner to embrace free agency, asserting the power of his wallet by spending freely and, at times, indiscriminately, and the first to greatly expand his team's revenues via a massive cable television deal, all of which gave him an enormous influence on the financial dynamics of the game. The result was the creation of the competitive balance tax in 2003.

That's the argument for Steinbrenner's induction, but there's an ample one against it as well. He was twice suspended from the game, first in 1974 and again in 1990. In '74, he pled guilty to making illegal contributions to Richard Nixon's 1972 presidential campaign and was suspended from baseball for 15 months. Sixteen years later, he was suspended permanently by commissioner Fay Vincent for paying gambler Howie Spira for information on New York's All-Star outfielder Dave Winfield (Steinbrenner was reinstated by acting commissioner Bud Selig in 1993). Steinbrenner, along with the other 25 owners, colluded not to sign free agents following the 1985, '86 and '87 seasons, a violation of the collective bargaining agreement that led to a $280 million settlement in favor of the players in November 1990.

The argument can also be made that his teams succeeded despite his constant meddling and reckless spending, and it was only during his two suspensions that the real baseball men in the team's front office -- general managers Gabe Paul and Gene Michael, respectively -- were able to assemble the cores of the two Yankees dynasties of his ownership. The real Steinbrenner Yankees, by that measure, were those of the 1980s and early '90s, a period that saw the franchise's longest championship drought since the arrival of Babe Ruth in 1920, a 17-year span of futility marked by Steinbrenner's impetuous management. Nothing illustrated that better than the fact that Steinbrenner made 16 managerial changes between 1978 and his suspension in the summer of 1990.

Steinbrenner was never the game's richest owner but he knew exactly how to leverage having the league's signature team in its largest market and he poured a great deal of those expanding revenues back into his team. If the yardstick being used for the non-players on this ballot is influence over the game, Steinbrenner's induction is assured.

Joe Torre, manager

New York Mets: 1977-81; Atlanta Braves: 1982-84; St. Louis Cardinals: 1990-95; New York Yankees: 1996-2007; Los Angeles Dodgers: 2008-10

Joe Torre has been a constant presence in Major League Baseball since his debut as a player at the end of the 1960 season, and remains so today as MLB's executive vice president for baseball operations. In the five seasons not covered by his managerial tenure above, he was a broadcaster for the Angels. In 18 seasons as a player, from 1960 to 1977, he hit .297/.365/.452 with 2,342 career hits, won the 1971 National League Most Valuable Player award and made nine All-Star teams. His JAWS score (Jay Jaffe's Hall of Fame evaluation system based on a combination of career and peak Wins Above Replacement) is better than that of the average Hall of Fame catcher.

As a manager, Torre ranks fifth all-time in wins, just behind La Russa and Cox, and has a better career winning percentage than La Russa as well as contemporary Hall of Famers Whitey Herzog, Tommy Lasorda and Dick Williams. He led a Braves team that had finished toward the bottom of the NL West in 1981 to the division title in '82 and won back-to-back NL West crowns with the Dodgers in 2008 and '09.

However, his greatest success, and the crux of his Hall of Fame argument here, came with the Yankees. New York made the postseason in all 12 of Torre's seasons as manager, winning six pennants in his first eight seasons and four World Series in his first five seasons in the Bronx. His 1998 squad set an American League record with 114 wins and, adding playoff victories, won more games in a single season (125) than any other team in history and is widely considered one of the greatest teams ever. As much as the foundation built by Michael and the spending power of Steinbrenner enabled that success, Torre's ability to bring a sense of calm and order back to the team was key to restoring dignity, respect and stability to a franchise that had embodied the Bronx Zoo epithet for most of the previous two decades.

Torre arguably deserves to be in the Hall of Fame as a player, but he is a no-brainer choice as a manager. The overall impact of his more than half-century in the game makes him second only to Miller (with whom Torre was a significant figure in the union as a player representative) as an obvious choice on this ballot.

The argument can thus be made that all six of these men deserve induction. At the very least, Torre, Cox and La Russa, the three signature managers of the 1990s, will be elected this year. The hope here is that Miller will join them, and there's a good chance that Steinbrenner will as well, but his will be a more controversial selection. Martin is an even more divisive candidate with less of a clear-cut case given the brevity of his various tenures. I suspect he will be passed over once again.

Nonetheless, the Hall of Fame should at the very least have three living inductees this year even without considering the player ballot. That's a welcome change after last year, which combined a shutout of the players with a pre-integration veterans ballot that inducted three men, none of whom lived to see the 1940s.

The 16-man committee charged with voting on the ballot includes: Hall of Fame players Rod Carew, Carlton Fisk, Paul Molitor, Joe Morgan, Phil Niekro and Frank Robinson; Hall of Fame managers Whitey Herzog and Tommy Lasorda; Major League executives Paul Beeston of the Blue Jays, Dave Montgomery of the Phillies, Jerry Reinsdorf of the White Sox and Andy MacPhail, formerly of the Twins, Cubs and Orioles; Steve Hirdt of Elias Sports Bureau; Bruce Jenkins of the San Francisco Chronicle; Baseball Writers' Association of America secretary-treasurer Jack O'Connell; and recently-retired Fort Worth Star-Telegram reporter Jim Reeves.